A Bad Day

On 9 November 1962, Jack McKay launched X-15-2 from the NB-52B on his way to what was supposed to be a routine heating flight (2-31-52) to Mach 5.55 and 125,000 feet. Just after the X-15 separated, Bob Rushworth (NASA-1) asked McKay to check his throttle position, and McKay verified it was full open. Unfortunately, the engine was only putting out about 35% power. In

theory, the X-15 could have made a slow trip back to Rogers Dry Lake, but there was no way of knowing why the engine had decided to act up, or whether it would continue to function for the entire trip. The low power setting seriously compounded the problems associated with energy management since the flight planners had calculated the normal decision times for an emergency landing at each of the intermediate lakebeds based on 100% thrust. The computer power at the time was such that there was no way to recompute those decision points in real time, so the mission rules dictated that the pilot shut down the engine and make an emergency landing.

McKay would have to land at Mud Lake.-194-

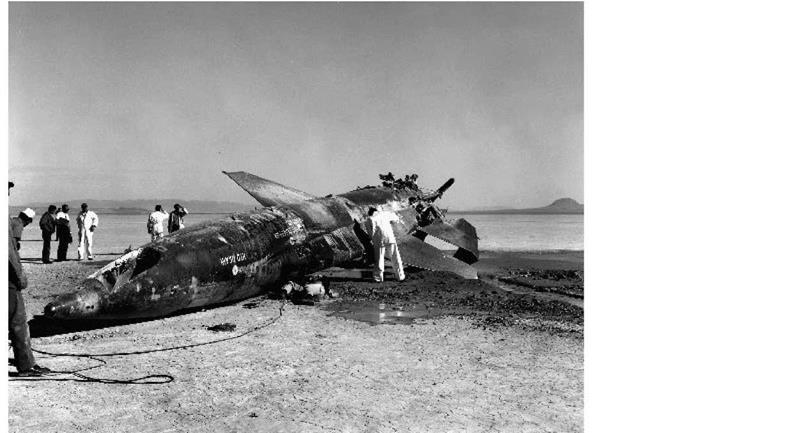

As emergency landing sites went, Mud Lake was not a bad one, being about 5 miles in diameter and very smooth and hard. When Rushworth and McKay decided to land at Mud, the pilot immediately began preparing for the landing. The engine was shut down after 70.5 seconds, the airplane turned around, and as much propellant as possible was jettisoned. It was looking like a "routine" emergency until the X-15 wing flaps failed to operate. The resulting "hot" landing (257 knots) caused the left main landing skid to fail, and the left horizontal stabilizer and wing dug into the lakebed, resulting in the aircraft turning sideways and flipping upside down. Luckily, McKay realized he was going over and jettisoned the canopy just prior to rolling inverted. The unfortunate result was that the first thing to hit the lakebed was McKay’s helmet.195

As was the case for all X-15 flights, the Air Force had deployed a rescue crew and fire truck to the launch lake. Normally it was a dull and boring assignment, but on this day they earned their pay. The ground crew sped toward the X-15, but when they arrived less than a minute later, they found that their breathing masks were not protecting them from the fumes escaping from the broken airplane. Fortunately, the pilot of the H-21 recovery helicopter noted the vapors from unjettisoned anhydrous ammonia escaping from the wreck and maneuvered his helicopter so that his rotor downwash could disperse the fumes. The ground crew was able to dig a hole in the lakebed and extract McKay. By this time, the C-130 had arrived with the paramedics and additional rescue personnel. McKay was loaded on the C-130 and rushed to Edwards, and the ground crew tended to the damaged X-15. At this point the airplane had accumulated a total free flight time of 40 minutes and 32.2 seconds.-11961

It had taken three years and 74 flights, but all of the emergency preparations had finally paid off. In this case, as for all flights, the Air Force had flown the rescue crew and fire truck to the launch lake before dawn in preparation for the flight. The helicopter had flown up at daybreak. The C – 130 had returned to Edwards and carried another fire truck to an intermediate lake (they were possibly the most traveled fire trucks in the Air Force inventory). The C-130, loaded with a paramedic and sometimes a flight surgeon, then began a slow orbit midway between Mud Lake and Edwards, waiting. Outside the program, some had questioned the time and expense involved in keeping the lakebeds active and deploying the emergency crews for each mission. The flight program was beginning to seem so routine. Inside the program, nobody doubted the potential usefulness of the precautions. Because of the time and expense, Jack McKay was resting in the base hospital, seemingly alive and well. Had the ground crew not been there, the result might have been much different.-197-

|

|

Jack McKay made an emergency landing at Mud Lake on 9 November 1962 after the XLR99 stuck at 35-percent power on Flight 2-31-52. Unfortunately, the wing flaps failed and the airplane was heavy with unjettisoned propellant, resulting in a very high 257-knot landing speed. As McKay touched down, the left rear skid failed and the airplane flipped over. Since Mud was a designated emergency landing site for this flight, fire trucks were standing by and paramedics were orbiting in a C-130 transport. McKay was airlifted to the hospital at Edwards with serious injuries. McKay recovered and flew 22 more X-15 flights and the X-15-2 was rebuilt into the advanced X-15A-

2. (NASA)

Although the post-flight report stated that the "pilot injuries were not serious," in reality Jack McKay had suffered several crushed vertebra that made him an inch shorter than when the flight had begun. Nevertheless, five weeks after his accident, McKay was in the control room as the NASA-1 for Bob White’s last X-15 flight (3-12-22). McKay would go on to fly 22 more X-15 flights, but would ultimately retire from NASA because of lasting effects from this accident.-1128!

X-15-2 had not fared any better-the damage was major, but not total. On 15 November 1962, the Air Force and NASA appointed an accident board with Donald R. Bellman as chair. The board released its findings, which contained no surprises, in a detailed report distributed during December 1962. Six months after the Mud Lake accident, the Air Force awarded North American a contract to modify X-15-2 into an advanced configuration that eventually allowed the program to meet its original speed goal of 6,600 fps (Mach 6.5). Because of the basic airplane’s ever – increasing weight, it had been unable to do this, by a small margin.!199!