Astronaut Wings

As near as can be determined, the three X-15s spent their entire career in and around Edwards, except for the occasional trip back to Inglewood to be repaired or modified. There was one exception, part of Project Eglin 1-62. On 2 May 1962, Jack Allavie and Bob White, along with a pressure-suit technician and a B-52 crew chief, took the NB-52A and X-15-3 to Eglin AFB in Florida for the 4-hour-long "Air Proving Ground Center Manned Weapons Fire Power Demonstration" attended by President John F. Kennedy. According to Allavie, "[W]e took off with an inert X-15 and flew all the way to Eglin AFB in Florida… that’s 1,625 miles and it was a simple flight. We landed there, put the X-15 on exhibit, and then flew it back to Edwards" on 5 May with a stop at Altus AFB, Oklahoma, for fuel. Photographic evidence shows a mission marking on the NB-52A depicting an X-15 oriented in the opposite direction of the regular launches (indicating, one guesses, a flight eastward) and the inscription "PRES. VISIT EGLIN FLA." Although it was by far the longest captive carry of the program, NASA did not assign the flight a program flight number.[185]

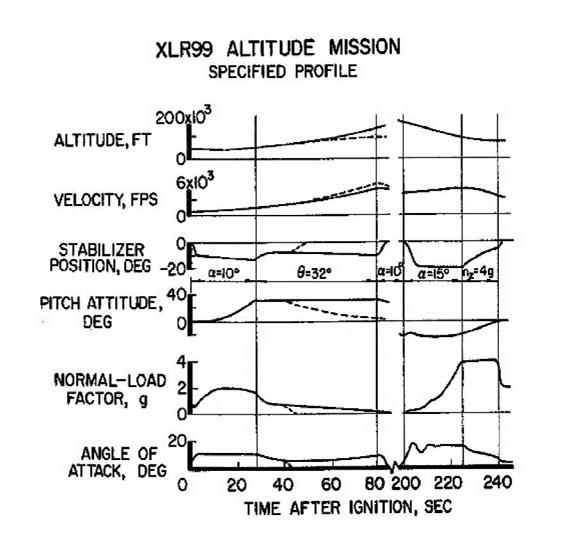

Back at Edwards, during the summer of 1962 Bob White made three flights in X-15-3 that demonstrated the potential problems of matching the preflight profile. On the first flight (3-5-9), White became disoriented during the exit and decided that he needed to push the nose down slightly so that he could visually acquire the horizon: "When we got up to 32 degrees, and at about 60 seconds in time, I guess it was just a small case of disorientation. I say a small case because I didn’t lose complete orientation but when I was up at this climb angle, and this is the first time that I’ve had this feeling, I looked at the ball, I had 32 degrees in pitch, but I had the darndest feeling that I was continuing to rotate. I couldn’t resist the urge just to push on back down until the light blue of the sky showed up. I never did get to the horizon, but I was satisfied that it wasn’t happening." By the time he was satisfied and began his climb again, his energy was such that he undershot his planned 206,000-foot peak altitude by 21,400 feet.[186]

White’s next flight (3-6-10) was only nine days later. This one was much better. White undershot by only 3,300 feet, about average for the program. White reported that the weather obscured most of his view of the ground: "I did look around quite a bit, and I was a little disappointed because of all the low clouds that obscured the coast line. I took a couple of definite looks because I wanted to try and scan up further north, and down along the Mexican coast, and pick out some places, but the cloud cover was so extensive that I couldn’t really do that. Then too, when you’re up there it feels like everything’s right under the nose. It was reassuring again to hear ground saying you’re right on profile and track. That eliminates any concern on the pilot’s part."^

If it seemed that White was getting better at hitting his planned altitude, the next flight would dispel any such thoughts. On 17 July 1962, White took X-15-3 on a flight that was supposed to go to 282,000 feet, which was sufficient to qualify him for an Air Force astronaut rating. The MH – 96 failed just before launch, which probably should have meant scrubbing for the day. Instead, White reached over and reset the circuit breakers. The MH-96 appeared to function correctly, so White called for a launch. White seemed to be trying to make up for the altitude he had not achieved on his last two flights. The climb angle was a bit steeper than called for, and the engine produced a bit more thrust than usual and burned a bit longer than expected. The result was a flight that was 32,750 feet higher than planned, setting a new Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) record for piloted aircraft of 314,750 feet and becoming the first winged vehicle to exceed 300,000 feet, the first flight above 50 miles, and the first X-15 flight that qualified its pilot for an astronaut rating. This time, as the first astronaut from Edwards, White was suitably impressed with the view:11881

You could just see as far as you looked. I turned my head in both directions and you see nothing but the Earth. It’s just tremendous. You look off and the sky is real dark. I didn’t think the impression would be much different than it was up around 250,000 feet, but I was impressed remarkably more than I was at 250,000 feet. It amazed me. I looked up and was able to pick out San Francisco bay and it looked like it was down over there off the right wing and I could look out, way out. It was just tremendous, absolutely tremendous. You have seen pictures from high up in rockets, or these orbital pictures of what the guy sees out there. That’s exactly what it looked like. The same thing.

White reentered and arrived over the high key at Mach 3.5 and 80,000 feet. The potential for a repeat of Armstrong’s excursion to Pasadena was present, but White had learned from Armstrong’s mistake: "I was mainly concerned at this time with the possibility of overshooting the landing point. I think that was my overriding consideration at this point. I went by the lake and turned it around, and when I went around in the turn I just pushed in on the bottom rudder so I could get the nose down and stay in where I had some q. I didn’t want any bounce in altitude. If I had gotten bounce, I would never have gotten back."11891

A wide sweeping turn over Rosamond brought White back to a more normal high key at 28,000 feet and subsonic speeds. He continued around for a near-perfect landing at 191 knots. Milt Thompson in the chase plane commented, "Nice, you really hit that… Bob," and Joe Walker in the NASA-1 control room finished by saying, "This is your happy controller going off the air." Despite having overshot the altitude by more than 10%, White flew the flight nearly perfectly, and data from this flight would be used for several years to check out and calibrate the fixed-base simulator.11901

|

|

The altitude missions demanded precise piloting, and even then, several variables beyond the control of the pilot could result in significant altitude errors. On 17 July 1962, Bob White took X – 15-3 on a flight that was supposed to go to 282,000 feet. The climb angle was a bit steeper than called for, the XLR99 produced a bit more thrust than usual, and it burned a bit longer than expected. The result was a flight that was 32,750 feet higher than planned, setting a new FAI record for piloted aircraft of 314,750 and becoming the first winged vehicle to exceed 300,000 feet, the first flight above 50 miles, and the first X-15 flight that qualified its pilot for an astronaut rating. (NASA)

Interestingly, this flight will probably remain an altitude record for airplanes as long as the FAI has a category for rocket-powered aircraft. In theory, it is possible to break the record one time. According to the rules, new records must exceed the old mark by 3%, meaning that somebody will have to fly at least 324,193 feet altitude to beat White’s record. However, according the FAI, the atmosphere ends at 328,099 feet (100 kilometers). Therefore, it will be impossible to better the subsequent record without going into space, which would disqualify the attempt (as happened with Joe Walker’s 354,200-foot flight). The chances of somebody managing to get above 324,194 feet without exceeding 328,098 feet are extremely remote. It has been 40 years and nobody has tried yet.[191]

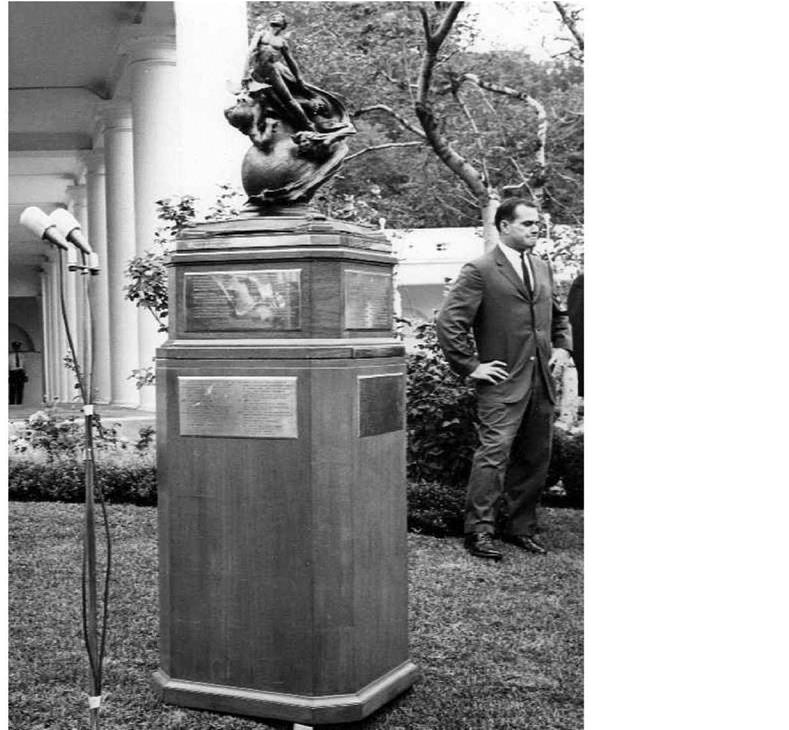

technological contributions to the advancement of flight and for great skill and courage as test pilots of the X-15." By this point Crossfield had been gone for two years, and Petersen had already left to become the commanding officer at VF-154. Nevertheless, all four pilots journeyed to Washington to accept the trophy on the South Lawn of the White House. The National Aeronautic Association annually awards the Collier Trophy, which is generally considered the most prestigious recognition for aerospace achievement in the United States. In the case of the X-15, the selection of the recipients was not arbitrary; it represented the first pilot from each organization (North American, Navy, NASA, and Air Force) to fly the airplane. The trophy itself was 7 feet tall and weighed 500 pounds, and when Kennedy presented it to Bob White (the spokesman for the group), he commented, "I don’t know what you are going to do with it."[192]

Later the same day the Air Force presented White with his astronaut wings during a small ceremony at the Pentagon, and that evening NASA feted all four pilots at a dinner where they received the NASA Distinguished Service Medal from Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson. NASA administrator James E. Webb commented at the dinner that the X-15 program was "a classic example of a most effective way to conduct research."

Since the beginning, the X-15 program had used four North American F-100 Super Sabres as Chase-1. However, the F-100 was getting old, and the AFFTC was happy to begin receiving new Northrop T-38 Talons during October 1961. Pilots reported that the T-38 "appears as good or better than the F-100F for X-15 support." The Air Force conducted several test flights, sans the X-15, to evaluate whether the T-38 could fly close chase at 45,000 feet when the NB-52 was in a right-hand turn-something the F-100 could not do. Such a capability would allow a right-hand NB-52 pattern prior to a launch, and would greatly improve ground telemetry reception during that period since the NB-52 fuselage would not block the X-15-to-ground line of sight. The previously used left-hand pattern resulted in a loss of telemetry during the turn until approximately 2 minutes prior to launch, but allowed the F-100F to remain in a suitable chase position during activation of the X-15 systems. The problem was that during a right turn the F – 100 was on the inside of the turn and had to fly at a slow indicated airspeed. In a left turn on the X-15 side, the F-100 was on the outside of the turn, flying at a higher and more acceptable indicated airspeed. The first flight (1-32-53) to use a T-38 was in July 1962 and the T-38 would be Chase-1 for almost every flight until the end of the program.-1193

|

|

On 18 July 1962, president John F. Kennedy presented the Robert J. Collier Trophy to the X-15 program. The award was accepted by Scott Cross field, Forrest Peterson, Joe Walker, and Bob White in a ceremony on the South Lawn of the White House.. The trophy is seven feet tall and weighs 500 pounds. (NASA)