CAN IT FLY?

As conceived at the time of the rollout in 1958, the contractor flight program consisted of four phases. The first was called "B-52 and X-15 Lightweight Captive Flight Evaluation" and was intended to verify the mated flight characteristics with an unfueled X-15, operational procedures, jettison characteristics (using dye), systems (APU, hydraulic, heat and vent, and electrical) operations, B-52 communications and observation, and carrier aircraft performance at launch speed and altitude. The second phase was the "X-15 Lightweight Glide Flight Evaluation" and involved launching an unfueled X-15 on an unpowered glide flight to verify the launch procedure, low-speed handling characteristics, and landing procedures.-1521

The third phase was the "B-52 and X-15 Heavyweight Captive Flight Evaluation," which was intended to replicate the first series of tests with a fully loaded X-15, demonstrate topping off the liquid-oxygen system, and verify that a full propellant load could be jettisoned using actual propellants. The last phase involved the initial "X-15 Powered Flight Evaluation" using the interim XLR11 engines. The schedule showed the first captive flight on 31 January 1959, with the first glide flight on 9 February 1959 and the first powered flight on 2 April 1959. Somehow, it would not work that way.-1531

X-15-1 arrived at Edwards on 17 October 1958, trucked over the foothills from the North American Inglewood plant. The second airplane joined it in April 1959, and the third would arrive later. As Air Force historian Dr. Richard P. Hallion later observed, "In contrast to the relative secrecy that had attended flight tests with the XS-1 a decade before, the X-15 program offered the spectacle of pure theater." It was not that the X-15 program necessarily relished the limelight – it simply could not avoid it after Sputnik.-1541

Beginning in December 1958, North American conducted numerous ground runs with the APUs installed in X-15-1 at Edwards. The company intended this to build confidence in the units before the first flights, but it did not turn out that way. Bearings overheated, turbines seized, and valves and regulators failed, leaked, or did not regulate. The mechanics would remove the failed part, rebuild it, and try again. More failures followed. Scott Crossfield later described this period as "sleepless weeks of sheer agony." Harrison Storms eventually got together with the senior management at General Electric, who sent Russell E. "Robby" Robinson to Edwards to fix the problem. For instance, Robinson noted that invariably after one APU failed, the other would follow within a few minutes. The engineers finally deduced that a sympathetic vibration transferred through the shared mounting bulkhead caused the second one to fail. North American devised a new mounting system that separated the APUs onto two bulkheads.-1551

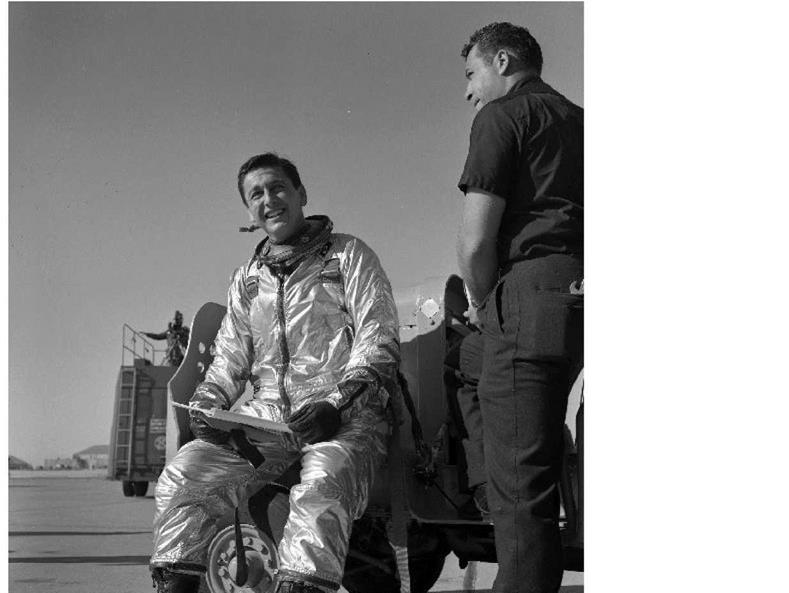

The North American pilot was Scott Crossfield, the person who arguably knew more about the airplane than any other individual did. After they performed various ground checks, technicians mated X-15-1 to the NB-52A and then conducted additional ground tests. All of this delayed the original schedule by about 60 days. When the day for the first flight arrived, Crossfield described it as a "carnival at dawn." Things were different during the 1950s. Crossfield and Charlie Feltz shared a room in the bachelor officer quarters (BOQ) at Edwards; there was no fancy hotel in town. They each dressed in a shirt and tie before driving to the flight line-nothing casual, even though Crossfield soon changed into a David Clark MC-2 full-pressure suit. When they got to the parking lot next to the NB-52 mating area, more than 50 cars were already waiting. The flight had been scheduled for 0700 hours. Based on his previous rocket-plane experience, Crossfield predicted they would take off no earlier than noon, and maybe as late as 1400.1561

Crossfield was pleasantly surprised. At 1000 hours on 10 March 1959, the mated pair took off on its scheduled captive-carry flight (retroactively called program flight number 1-C-1). It had a gross take-off weight of 258,000 pounds, and lifted off at 172 knots after a ground roll of 6,085 feet. During the 1 hour and 8 minute flight, Captains Charlie Bock and Jack Allavie found that the NB-52 was an excellent carrier for the X-15, as was expected from numerous wind-tunnel and simulator tests.-1571

|

|

Scott Cross field spent many hours in his David Clark full-pressure suit while the X-15-1 was prepared for its initial flights. Despite the daytime temperatures in the desert, Crossfield believed that his presence, ready to go, kept ground crew morale high. (NASA)

During the captive flight, Crossfield exercised the X-15 flight controls, and the recorders gathered airspeed data from the flight test boom to calibrate the instrumentation. Bock and Allavie found that the penalties imposed by the X-15 on the NB-52 flight characteristics were minimal, and flew the mated pair up to Mach 0.85 at 45,000 feet. Part of the test sequence was to make sure the David Clark full-pressure suit worked as advertised, although Crossfield had no doubts. This was a decidedly straightforward test. The suit should inflate as soon as the altitude in the cockpit went above 35,000 feet. As the mated pair passed 30,000 feet, Crossfield turned off the cabin pressurization system and opened the ram air door to equalize the internal pressure with the outside air. Once the airplanes climbed above 35,000 feet, Crossfield felt the suit begin to inflate, and "from that point on [his] movements were slightly constrained and slightly awkward." Still, Crossfield could reach all of the controls, including the hardest control in the cockpit to reach: the ram air door lever. Crossfield closed the door, and as the cockpit repressurized, the suit relaxed its grip. Pilots repeated this test on every X-15 flight until the end of the program. Near the end of the flight, Crossfield lowered the X-15 landing gear just to make sure it worked, even if it looked a little odd while still mated to the NB-52.[58]

The next step was to release the X-15 from the NB-52 to ascertain its gliding and landing characteristics. North American rescheduled the first glide flight for 1 April 1959, but aborted it when the X-15 radio failed. The NB-52A and X-15 spent 1 hour and 45 minutes airborne conducting further tests in the mated configuration. A combination of radio failure and APU problems caused a second abort on 10 April. Yet a third attempt aborted on 21 May 1959 when the X-15 stability augmentation system failed and a bearing in the no. 1 APU overheated after approximately 29 minutes of operation.-1591

The problems with the APU were the most disturbing. All of these flights encountered various valve malfunctions, leaks, and speed-control problems with the APUs, all of which would have been unacceptable during research flights. Tests conducted on the APU revealed that extremely high surge pressures were occurring at the pressure relief valve (actually a blowout plug) during the initial peroxide tank pressurization. The installation of an orifice in the helium pressurization line immediately downstream of the shut-off valve reduced the surges to acceptable levels. Engineers decided that other problems were unique to the captive-carry flights and deemed them of little consequence to the flight program since the operating scenario would be different. Still, reliability was marginal at best. The APUs underwent a constant set of minor improvements during the flight program, but continued to be a source of irritation until the end.*60

On 22 May, North American conducted the first ground run of the interim XLR11 engine using X – 15-2 at the Rocket Engine Test Facility. Scott Crossfield was in the cockpit for the successful test, clearing the way for the eventual first powered flight-if X-15-1 could ever make its unpowered flight. Another attempt at the glide flight on 5 June 1959 aborted even before the NB-52 left the ground, when Crossfield reported smoke in the cockpit. Investigation showed that a cockpit ventilation fan motor had overheated. The continuing problems with the first glide flight were beginning to take their toll, both physically and mentally, on all involved.*61

Because of the lessons learned on the aborted glide flights and during the XLR11 ground runs, engineers modified numerous pieces of equipment on the X-15. These included the APUs, their support brackets, the mounting bulkheads, and the bearings inside them. North American also improved the flight control system’s mechanical responsiveness. In addition, technicians accomplished a great deal of work on the various regulators and valves, particularly in the hydrogen-peroxide systems. Storms remembered, "[I]n the final analysis, the regulators and valves were the most troublesome hardware in the program insofar as reliability was concerned.’,[62]