DRY LAKES

Although they had one of the most ideal test locations in the world, the Air Force and NACA could not simply go out and begin conducting X-15 operations. Several hurdles had to be overcome before the X-15 could ever do more than just conduct short flights over the Edwards reservation.

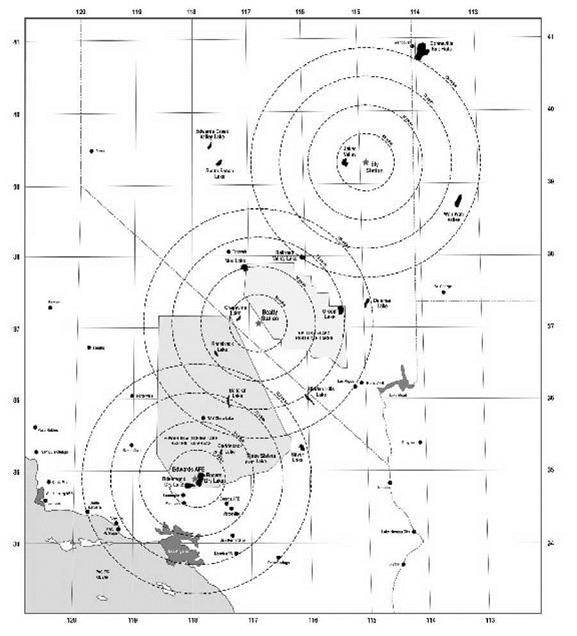

It had been recognized early during planning for the X-15 flights that suitable contingency landing locations would need to be found in the event of an abort after separation from the B-52 carrier aircraft, or if problems during the flight forced the pilot to terminate the mission before reaching Edwards. Since North American had designed the X-15 to land on dry lakebeds, the logical course of action was to identify suitable lakebeds along the flight path-in fact, these

lakebeds had been one of the factors used to determine the route followed by the High Range.

The Air Force and NACA had to identify lakebeds that would enable the X-15 to always be within gliding range of a landing site. In addition, the flight planners always selected a launch point that allowed the pilot a downwind landing pattern. Normally, the launch point was about 19 miles from the lakebed runway and the track passed the runway 14 miles abeam. To establish the proper launch point, flight planners used the fixed-base simulator to determine the gliding range of the airplane, including both forward glides and making a 180-degree turn and returning along its flight path. Another consideration was that the flight planners needed to selected lakes that would provide an overlap throughout the entire flight.[69]

The first hurdle for the Air Force was to secure permission from the individuals and several government agencies that owned or controlled the lakebeds. Next was seeking permission from the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA-it became an administration later) to conduct flight operations over public land.

Although responsibilities concerning the lakebeds continued throughout the life of the X-15 program, there were several spurts of activity (two major and one minor) concerning them. The first occurred, logically enough, just before the beginning of the flight program when efforts began to secure the rights to the lakebeds needed for the initial flight tests. The second involved securing the lakes needed for the higher-speed and higher-altitude flights made possible by the introduction of the XLR99 engine. One final push later in the program tailored the set of lakes for the improved-performance X-15A-2 and its external tanks.

Eventually, 10 different launch locations would be used, including eight dry lakes: Cuddeback supported a single launch; Delamar was the most used, with 62 launches; Hidden Hills saw 50 launches; Mud hosted 34; Railroad was used for only 2; Rosamond was used for 17, Silver hosted 14, and Smith Ranch was used for 10. In addition, the Palmdale VOR (OMNI) hosted eight launches, and a single flight originated over the outskirts of Lancaster. Hidden Hills was usually the intended site for the abortive 200th flight. The vast majority of these flights (188) would land on Rogers Dry Lake. Two would land at Cuddeback, one at Delamar, four at Mud, one at Rosamond, one at Silver, and one at Smith Ranch. The X-15-3 broke up in flight and did not land on its last flight.[70]

Rosamond Dry Lake, several miles southwest of Rogers, offered 21 square miles of smooth, flat surface that the Air Force used for routine flight test and research operations and emergency landings. This dry lakebed had served as the launch point for many of the early rocket-plane flights at Edwards. It is also the first lakebed that most visitors to Edwards see, since the road from Rosamond (and Highway 14) to Edwards crosses its northern tip on its way to the main base area. Scott Crossfield would make the X-15 glide flight over Rosamond Dry Lake, and no particular permission was necessary to use Rosamond since the lakebed was completely within the restricted area that made up the Edwards complex. Unfortunately, the lake was only 20 miles away from the base, so it did not allow much opportunity for high-speed work.

The Rogers and Rosamond lakebeds are among the lowest points in Antelope Valley, and they collect seasonal rain and snow runoff from surrounding hills and from the San Gabriel Mountains to the south and the Tehachapi Mountains to the west. At one time, the lakebeds contained water year-round, but changing geological and weather patterns now leave them wet only after infrequent rain or snow. A survey of the Rosamond lakebed surface showed its flatness, with a curvature of less than 18 inches over a distance of 30,000 feet.[71]

Beginning in early 1957, North American, AFFTC, and NACA personnel conducted numerous evaluations of various dry lakes along the High Range route to determine which were suitable for X-15 landings. The initial X-15 flights required 10 dry lakes (five as emergency landing sites near launch locations, and five as contingency landing sites downrange) spaced 30-50 miles apart.^72

The processes to obtain permission to use the various lakebeds outside the Edwards complex were as diverse as the locations themselves. For instance, permission to use approximately 2,560 acres of land at Cuddeback Lake as an emergency landing location was sought beginning in early 1957, with first use expected in January 1959. The lakebed was within the land area reserved for use by the Air Force at George AFB, California, but the Department of the Interior controlled the lakebed itself. Since the Air Force cannot acquire land directly, officials at the AFFTC contacted the Los Angeles District of the Army Corps of Engineers, only to find out that George AFB had already requested the Corps to withdraw the land from the public domain. The Bureau of Land Management controls all land in the public domain, although control may pass to other government agencies (such as the military) as stipulated in various laws (U. S. Code Title 43, for example). At the time, the Corps of Engineers acted as the land management agent for the U. S. Air Force, and John J. Shipley was the chief of the real estate division for the Los Angeles District.

|

|

This map shows the general location of the lakebeds as well as the radar coverage afforded by the three High Range stations. The two primary restricted airspace areas are shaded, although the entire flight path of the X-15 was restricted on flight day. (Dennis R. Jenkins)

Officials at George intended to use the lakebed as an emergency landing site. In turn, on 17 May 1957 the Corps wrote to the Bureau of Land Management on behalf of the Secretary of the Air Force, requesting a special land-use permit for Air Force operations at the lake. When the Los Angeles District received the request from the AFFTC, Shipley contacted Lieutenant Colonel C. E. Black, the

installations engineer at George AFB, requesting that a joint-use agreement be set up that would permit sharing the lake with the AFFTC for X-15 operations.-1731

By the end of July 1959, the Bureau of Land Management had approved the permit, and George AFB had agreed in principle to the sharing arrangement. The special-use permit gave George AFB landing rights for several years, and permitted the lakebed to be marked as needed to support flight operations. John Shipley, very intelligently, decided that the joint-use agreement between the AFFTC and George was an internal Air Force affair and bowed out of the process after the issuance of the Bureau of Land Management permit. Although there seemed to be no particular disagreement, the joint-use agreement had a long gestation period. The special-use permit was granted at the beginning of August, but at the end of September Colonel Carl A. Ousley, the chief of the Project Control Office at the AFFTC, questioned why a written joint-use agreement had not been signed. Major Resiner at George replied on 14 October that he had received verbal approval from all parties, but written approval was required from two separate Air Force commands (the ARDC and the Tactical Air Command (TAC)), the Corps of Engineers, and the Bureau of Land Management. He foresaw no difficulties in obtaining the signatures, and apparently the process worked itself out within a suitable period since there appears to have been no further correspondence on the matter. The joint-use agreement with George AFB essentially stated that the AFFTC was responsible for any unique preparations and marking of the lakebed required to support X-15 operations, although George did offer to supply emergency equipment and personnel as needed.-741

Simultaneously with the request to use Cuddeback, the AFFTC issued a similar request for Jakes Lake and Mud Lake, both in Nevada. Originally, the X-15 program had wanted to use Groom Lake, Nevada, as a launch site instead of Mud Lake. However, the security restrictions in place at Groom Lake (also known as "The Ranch") to protect the CIA-Lockheed reconnaissance programs led the AFFTC and NASA to abandon plans to use this facility. Officials at Nellis suggested Mud Lake as a compromise between the needs of the X-15 program and the highly classified CIA programs.751

The AFFTC asked for approximately 2,500 acres of land in the public domain at Jakes Lake; at Mud Lake, the request was for 3,088 acres. The indefinite-term special-use permits sought the right to install fencing to keep cattle from grazing in certain areas. Several ranchers had grazing rights on the public domain land, so this required modifying these agreements and compensating the ranchers with Air Force funds. In this case the Air Force did not want to remove the land from the public domain, but it did want to use approximately 9,262 acres of land at Mud Lake that had already been withdrawn from the public domain for use as part of the Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range.761

October 1957 for approval and funding. By the end of January 1958, however, Lieutenant Colonel Donald J. Iddins at the AFFTC began to worry that the process was taking too long. The X-15 needed the lakes in July 1959, and there was no evidence of final action. Part of the problem was that land actions involving over 5,000 acres (which the two actions together did) required approval from the House Armed Services Committee. The AFFTC reminded the chief of engineers that they did not want to remove the land from the public domain, which seemingly eliminated the need for congressional approval, and brought the situation to the attention of the X-15 Project Office during a management review at Wright Field on 5 February 1958. The result was a renewed effort to ensure that all three lakes (Cuddeback, Jakes, and Mud) were available for X-15 use on schedule, including the right to build roads to the lakes, marking approach and landing areas, and fencing certain areas if necessary to ensure the safety of the X-15.-177

On 14 February 1958, the chief of engineers responded that he had initiated the process to grant special-use permits, but had terminated the effort when he noted that the AFFTC wanted to fence off the land. However, the law did not permit fencing to be erected on special-use permitted land. This meant that the land would have to be withdrawn from the public domain after all, or go unfenced. It appears that the answer to the problem was obtained by the AFFTC agreeing to a reduction in the Mud Lake acquisition to just under 2,500 acres (versus the original 3,088), bringing the total to under 5,000 and circumventing congressional approval. This allowed the land to be withdrawn from the public domain, and some of it was fenced as needed to keep stray cattle from wandering onto the marked runway.-178

Simply getting access to the lakebeds was not always sufficient. For instance, Mud Lake was in the extreme northwest corner of Restricted Area R-271, meaning that Sandia Corporation, which controlled R-271 for the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), had to approve its use. A "Memorandum of Understanding between the Air Force Flight Test Center and Sandia Corporation" allowed AFFTC support aircraft to operate in the immediate vicinity of Mud Lake during X-15 flights. The AFFTC had to furnish flight schedules to Sandia one week before each anticipated mission, and Sandia made the point that it had no radar search capability and could not guarantee that the area was clear of traffic. Sandia also agreed not to schedule any tests within the restricted area that might conflict with X-15 flights. Once approved by Sandia, the AFFTC sought additional approval from Nellis AFB since Mud Lake was also within the Las Vegas Bombing and Gunnery Range. This approval was somewhat easier to negotiate because it was obtained from another Air Force organization.-1791

On 3 November 1958, a team from the AFFTC visited Mud Lake to conduct a preliminary study of lakebed conditions and to determine what action would be required to clear areas of the lakebed for use as a landing strip. When the group from the Flight Test Operations Division and Installations Engineer Division arrived over the lake, the pilot made several low passes to orient the group and obtain a general knowledge of the various obstructions that might conflict with landing on the lakebed. What the group saw was a general pattern of obstructions running east to west in a straight line across the center of the lakebed. The team landed at the Tonopah airport and proceeded by car to the lake, 16 miles away, for a closer inspection.-1801

They found that the obstructions observed down the center of the lake were a series of old gunnery-bombing targets dating from World War II. Practice bodies, wooden stakes, and goodsized rocks used to form bull’s-eyes for bombing practice littered the lakebed. The targets were in a narrow straight band down the center of the lake from west to east, but the debris covered a considerably wider area. As would become standard practice on all the lakes, the group dropped an 18-pound steel ball from a height of 6 feet and measured the diameter of the resulting impression. This gave a good indication of the relative hardness of the surface and its ability to support the weight of the X-15 and other aircraft and vehicles. At the edges of the lake, the ball left impressions of 3.25 inches or so, while toward the center of the lake the impressions were only 2.25-3.0 inches in diameter. At the time, the Air Force believed that impressions of 3.125 inches or less were acceptable. The general surface condition of the lakebed varied from relatively smooth and hard to cracked and soft. Although it was not ideal, the group thought the lakebed could be made useable with minor effort.-1811

More lakebed evaluations followed on 13-14 July 1959. X-15 pilot Bob White and the AFFTC chief of flight test operations, Colonel Clarence E. "Bud" Anderson, used a Helio L-28 Super Courier aircraft to visit 12 dry lakes along the High Range route. At each lake, Anderson and White dropped the "imperial ball" from six feet and measured the diameter of the resulting impression.

By this time, the Air Force had changed the criteria slightly: a diameter of 3.25 inches was acceptable, and anything above 3.5 inches was unacceptable. The survey included an evaluation of the surface hardness, surface smoothness, approximate elevation, length and direction of possible runways, and obstacles. Anderson remembers that there was "only one lake where we had to make a full power go-around as we watched the tires sink as we landed." Many future surveys would take personnel from AFFTC, NASA, and North American to most of the larger dry lakes along the High Range route.-1821

In addition, on 13 July 1959, four FAA representatives and two members of the AFFTC staff held a meeting at the FAA 4th Region Headquarters in Los Angeles to discuss using Silver Lake as a launch site for the X-15. Since some of the X-15 flight corridor would be outside existing restructured airspace, FAA approval was necessary. The FAA claimed jurisdiction under Civil Aeronautics Regulation 60.24, but was anxious to assist the Air Force within the limits of the law. The Air Force intended to use Silver Lake launches for early X-15 flights with the XLR11 engines. The proposed 100-mile flight path consisted of Silver Lake, Bicycle Lake, Cuddeback and/or Harpers Lake, and then on to landing at Edwards. The FAA had no particular problem with the concept, but since its charter was to protect the safety of all users of public airspace, it believed that certain restrictions needed to be in place before the flights could be approved. The participants spent most of the meeting discussing possible operational problems and concerns, and then developing limitations or restrictions that mitigated the concerns.1881

For Silver Lake launches, both the launch and the landing were performed in a restricted airspace called a "test area." Silver Lake was inside Flight Test Area Four, while Edwards was at the center of Flight Test Area One. However, none of the test areas surrounding Edwards were restricted 24 hours per day, or seven days per week. In fact, they were open to civilian traffic most of the time, and their closure had to be coordinated with the FAA (the airspace immediately around Edwards was always closed to civilian traffic). In addition, the flight path from Silver Lake to Edwards would take the X-15 out of restricted airspace and into civilian airspace for brief periods. Future flights using the northern portion of the High Range would also be outside normal test areas. The FAA, therefore, needed to approve the plans and procedures for using that airspace.1841

On 1 September 1959, L. N. Lightbody, the acting chief of the General Operations Branch of the Los Angeles office (4th Region) of the FAA wrote to Colonel Roger B. Phelan, deputy chief of staff for operations at the AFFTC. The letter contained a "certificate of waiver covering the release of the X-15 research vehicle over Silver Lake" subject to some special limitations. The FAA imposed the limitations to ensure "maximum safety not only to your AFFTC personnel and equipment, but also to other users of the immediate airspace. Further, the communications requirements will insure the blocked airspace may be returned to its normal use with minimum delay." The FAA approved the certificate of waiver (form ACA-400) on 1 September 1959 and listed the period of waiver as 1

October 1959 to 31 March 1961, although it was subsequently extended to 1 July 1963, and later still through the end of 1969.[85]

Given the effort that accompanied the acquisition of Cuddeback Lake in late 1957 and early 1958, it is surprising that the first serious survey of the lake does not appear to have taken place until 7 October 1959. Of course, conducting detailed surveys significantly ahead of the anticipated use was not a particularly useful exercise since the periodic rains that kept the lakebeds useable also changed their character each time, as did the effects of other vehicles (such as cars). By this time, the X-15 had already made its first two flights from over Rosamond Dry Lake, landing each time at Rogers. Since the Air Force expected the X-15 to begin rapidly to expand its flight envelope, North American sent George P. Lodge to Cuddeback in an Air Force Piasecki H-21 Shawnee helicopter.1861

Lodge conducted the standard hardness tests by dropping the same "imperial ball" used in the other surveys. He found that the ball left an impression of about 3 inches (which was considered acceptable) at the southern end of the proposed runway, but quickly degraded to 4-4.5 inches by the northern end. He noted that these measurements compared unfavorably to tests on Rogers (2 inches) and Rosamond (2 inches) conducted after the last rains. A note emphasized that there were a set of deep ruts running the length of the runway made by a vehicle when the lake was wet, and that although it was only a single set of ruts, they "wander around to some extent." The nature of the lakebeds was such that grading or other mechanical methods could not repair major damage-only nature could do that. Lodge recommended that "Cuddeback lake, in its present condition, not be considered as an alternate landing site for the X-15 airplane and should be used only as a last resort in an extreme emergency." He warned that "should a landing be attempted with the X-15 airplane on Cuddeback lake in its present condition, there would be more than a 50-50 chance of wiping out the nose gear." It was clear that the lakes had both good and bad qualities: they were largely self-repairing each time it rained, but they could also be selfdestroying by the same process.-1871

Two weeks later, Lodge, who was a flight safety specialist for North American, performed a survey of Silver Lake and nine other lakes to determine their suitability as emergency landing sites. At Silver, Lodge found that the prevailing wind was out of the north, with the best landing heading estimated at 200-310 degrees magnetic. The southern portion of the lake was soft with numerous sinkholes, and not satisfactory for touchdown. Lodge also found an abandoned railroad bed, approximately 2 feet high and 10 feet wide, running north to south across the east side of the lakebed. There was also a dirt road with deep ruts running east to west across the northern part of the lake, a paved road going from Baker to Death Valley along the eastern perimeter, and another dirt road (this time with no ruts) running diagonally northwest to southeast.-1881

Despite these obstacles, there was approximately 16,000 feet of satisfactory lakebed between the soft southern portion and the northern road. There were a few sinkholes, most measuring about 7 inches across and 3-4 inches deep, but the Air Force would fill these before use. The usual imperial-ball tests resulted in impressions between 2.9 and 3.7 inches in diameter, although the main area was on the lower end of that range. In addition, Lodge pounded both 3/8-inch and 1/2-inch steel rods into the ground with 200 pounds of force to determine what the condition of the soil was under the upper crust. The 3/8-inch rod generally penetrated between 1 and 3 inches, while the 1/2-inch rod penetrated between 0.25 and 1.5 inches. The results of the tests led Lodge to recommend a location for a marked runway. Of the other nine lakebeds visited,

Lodge landed only on the east and west lakes in the Three Sisters group, and determined that both were satisfactory for emergency use despite having "a few rocks and ammo links strewn 1891

about.

As 1959 ended, George Lodge was a busy man, and at the end of November he conducted yet another lake survey, this time of approximately 50 lakes in California, Nevada, and Utah. Again, the intent was to find suitable emergency landing sites for the X-15 as it expanded its flight-test program. The test methods Lodge used on the lakes were the same as he had used the previous month at Silver Lake.-90

The Air Force and NASA continued to survey the established and previously used lakebeds periodically, particularly after it rained to determine that the lakebed was dry enough to support operations and that no sinkholes or gullies existed. Changing the direction of the available runways on a lakebed also required a revised survey. For instance, in early December 1959 Lodge conducted a new survey of Rosamond Dry Lake to determine whether the lake would support a marked runway running northeast to southwest. Marked runways already existed on headings of 10-190 degrees and 70-250 degrees. Starting from a location in the southwest corner of the lakebed, Lodge inspected a heading of approximately 30 degrees, roughly toward the telemetry station located on the edge of the lake. He found that the lakebed was hard and smooth for 2 miles, moderately smooth at 2.5 miles, smooth again at 3 miles, moderately rough at 3.5 miles, and rough from 4 miles to the edge of the lakebed. Imperial-ball drop tests yielded diameters of about 2.5 inches across the route. The conclusion was that the runway was practical, and, as viewed from above, would result in a runway approximately halfway between the two existing runways, with all three converging at the southwest edge of the lakebed.-1911

The second round of lake acquisitions began when the XLR99 engine came on line. First up was securing rights to use Hidden Hills dry lake, slightly west of the Hidden Hills Ranch airstrip. Simulator studies had confirmed that Hidden Hills would be ideal as an emergency landing site during the launches for the initial XLR99 flights that needed to be conducted further uprange than the XLR11 flights. The lakebed would continue to be used as a contingency site as the program continued to launch further uprange into Utah. At the beginning of 1960, it was expected that the program would need access to the lake by 1 October 1960.[92]

However, schedules change, and the XLR99 flight dates kept slipping. A revised plan showed that the XLR99 research buildup flights would use Silver Lake and Hidden Hills Lake in California, Mud Lake in Nevada, and Wah Wah Lake in Utah as launch sites. The program needed various intermediate lakes along the upper portion of the High Range to provide complete coverage for emergency landings along the route. The Air Force would staff the intermediate lakes with crash and emergency personnel during flights. Additional contingency lakes would have runways marked on them, but would not be staffed with support personnel. At first the AFFTC and NASA had wanted to mark "all lakes with a satisfactory 10,000 feet landing surface" to provide an additional factor of safety for the X-15 program. Although no plans existed to use these lakes, the planners believed that marking them would also allow continued X-15 operation when a primary intermediate lake was wet. However, legal personnel indicated that there was "NO possibility" (emphasis in original) of marking any lake unless a right-to-use permit was obtained. Since personnel and funds did not exist to negotiate all the required permits, this plan was abandoned and a list of essential contingency sites was drawn up.[93]

The 30 September 1960 plan included launching immediate flights from Silver Lake, with the west lake at Three Sisters and Cuddeback acting as intermediate emergency sites. By 1 February 1961, operations would move to Hidden Hills, with Cuddeback as the intermediate site. On 1 April, Mud Lake would become the primary launch lake, with Grapevine and Ballarat as the intermediate sites, and contingency sites located at Panamint Springs and Racetrack. Two months later the launches would move to Wah Wah Lake, with Groom Lake, Delamar, and Hidden Hills becoming the intermediate sites, and Dogbone and Indian Springs the contingency sites. The AFFTC sought permission from Nellis to use the last two sites because they were located on the Las Vegas range, as was Mud Lake.[94]

Planners had always considered Smith Ranch Lake as a backup site to Wah Wah Lake, using Mud Lake as the intermediate site and the same contingency sites used during Mud Lake launches. This was still true at the end of February 1961. The program expected to begin launches from Hidden Hills in March 1961, and the launch lake still needed to be surveyed and marked. NASA expected to begin using Mud Lake in April 1961 and two of the support lakes (Grapevine and Panamint) still required use permits, while Ballarat had replaced Racetrack as the second contingency site. The program still needed to survey and mark all three of the support lakes. Launches from Wah Wah would begin in June 1961, and all of the sites along that route (except for Hidden Hills) still had to be "acquired," surveyed, and marked. As the program continued, however, it abandoned plans to use Wah Wah Lake, in part because of difficulties in obtaining permission to use the Nellis contingency sites (particularly Groom Lake) and airspace rights over Nevada’s restricted areas. Instead, the government eventually acquired the alternate launch site at Smith Ranch Lake, although flights from this point did not begin until June 1963.[95]

|

|

Determining if a lakebed could support the weight of an X-15 and its support airplanes was a relatively non-technical endeavor. A large steel ball, nicknamed the "imperial ball" was dropped from a height of six feet and the resulting impression was measured. For most of the program, a diameter of 3.25 inches or less was considered acceptable to support operations. Neil Armstrong is kneeling beside the ball in this June 1958 photo at Hidden Hills. (NASA)