Crossfield’s Crusade

By the beginning of the X-15 program, the WADC Aero Medical Laboratory had only partly succeeded in developing a full-pressure suit, almost entirely with the David Clark design. This led to a certain amount of indecision regarding the type of garment needed for the X-15. However, North American proposed the use of a full-pressure suit as a means to protect the pilot during normal operations and emergency escape.

Despite the early state-of-development of full-pressure suits, Scott Crossfield was convinced they were necessary for the X-15. Crossfield also had great confidence in David Clark—both the company and the man. In fact, the detail specification of 2 March 1956 required North American to furnish just such a garment, and the company issued a specification for a full-pressure suit to the David Clark Company on 8 April 1956. Less than a month later, however, the X-15 Project Office, on advice from the Aero Medical Laboratory, advised North American to plan to use a partial-pressure suit. It was the beginning of a heated debate.-981

North American, and particularly Scott Crossfield, refused to yield, and during a meeting in Inglewood on 20-22 June 1956 the Air Force began to concede. David Clark demonstrated a full – pressure suit, developed for the Navy, during preliminary X-15 cockpit mockup inspection. Although the suit was far from perfected, the Aero Medical Laboratory believed that "the state-of – the-art of full pressure suits should permit the development of such a suit satisfactory for use in the X-15.""

During a meeting on 12 July 1956, representatives from the Air Force, Navy, and North American reviewed the status of full-pressure suit development, and the Aero Medical Laboratory committed to make the modifications necessary to support the X-15. The North American representative, Scott Crossfield, agreed that the Aero Medical Laboratory should provide the suit for the X-15. Crossfield insisted that the laboratory design the garment specifically for the X-15 and make every effort to provide an operational suit by late 1957 to support the first flight. The X-15 Project Office accepted responsibility for funding the development program. Crossfield could not legally change the suit from a contractor-furnished item to government-furnished equipment, but agreed to recommend that North American accept such a change. There was little doubt that Charlie Feltz would concur."0-

Although the 12 July agreement effectively settled the issue, the paperwork to make it official moved somewhat more slowly. The Air Force did not change the suit from contractor-furnished to government-furnished until 8 February 1957. At the same time, the Aero Medical Laboratory issued a contract to the David Clark Company for the development of a full-pressure suit specifically for the X-15.-1011

The first X-15 suit was the S794-3C, which incorporated all of the changes requested after a brief period of evaluating the first two "production" S794 suits. The complete suit with helmet, boots, and back kit weighed just 37 pounds. David Clark shipped this third suit to Inglewood for evaluation in the X-15 cockpit mockup from 7-13 October 1957. While at North American, the suit underwent pressure checks, X-15 cockpit compatibility evaluations, ventilation checks, and altitude-chamber runs. Unfortunately, the altitude-chamber runs proved pointless since the North American chamber only went to 40,000 feet and the suit controller had been set to pressurize above 40,000 feet.-102

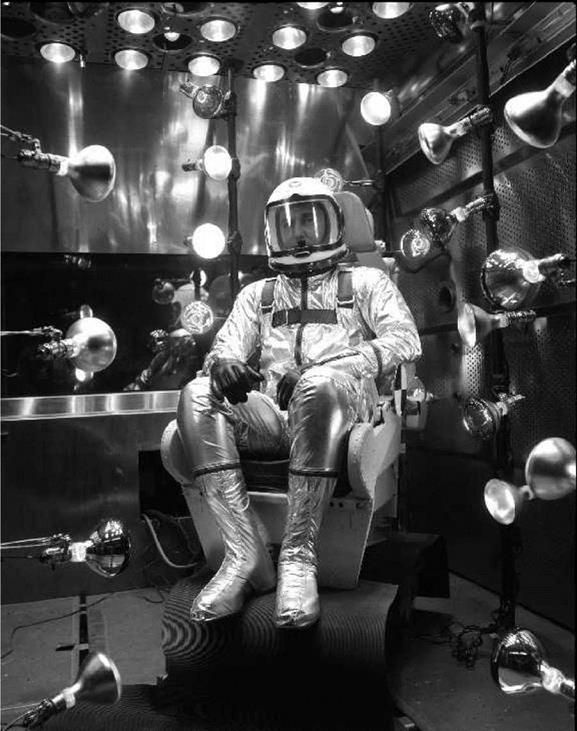

The suit was then taken to the Aero Medical Laboratory for evaluation, and on 14 October was demonstrated in the Wright Field centrifuge during two 15-second runs at 7 g. The following day, 23 more centrifuge runs demonstrated the anti-g capability of the suit, which proved satisfactory. On 16 October, the suit underwent environmental testing at temperatures up to 165°F. The ventilation of the suit at these temperatures was unsatisfactory, but David Clark engineers understood the issue and the government did not consider it significant. Mobility tests were conducted in the centrifuge on 17 October at flight conditions up to 5 g with satisfactory results, and altitude chamber tests ended at 98,000 feet for 45 minutes. As a result of these evaluations, the Air Force requested numerous minor modifications for subsequent suits, but the Aero Medical Laboratory formally accepted the S794-3C on 12 November 1957.-103

The list of modifications required for the S794-4 suit took four pages, but they were mostly minor issues and did not represent a significant problem for the David Clark Company, although the resulting suit was almost 3 pounds heavier. Scott Crossfield demonstrated this suit during a cockpit inspection on 2 December 1957 when he put the suit on, inflated it to 3 psi, walked from one end of the room to the other (a distance of some 100 feet), and then entered the X-15 cockpit without assistance. Those in attendance were favorably impressed.-1104!

On 16 December 1957, David Clark took the S794-4 suit to Wright Field for further evaluation, and then to NADC Johnsville for centrifuge testing on 17-18 December. These centrifuge tests were much more realistic than the limited evaluations conducted at Wright Field on the previous suit, and included complete simulated X-15 flights. After some minor modifications, the Aero Medical Laboratory formally accepted the suit on 20 February 1958.-105-

The S794-5 suit, the first true "production MC-2," incorporated 34 changes. The Air Force sent the completed suit to Wright Field on 17 April 1958, and then to Edwards for flight evaluations. Personnel at Edwards had modified the back cockpits of a T-33 and F – 104B to accommodate the suit for the tests. The first flight in the T-33 on 12 May 1958 resulted in several complaints, primarily citing a lack of ventilation because no high-pressure air source was available. Initial concerns about a lack of mobility eased after the third flight as the pilot became more familiar with the suit. The suit seemed to offer adequate anti-g protection up to the 5-g limit of the T-33. Tests in the F-104B proved to be more comfortable, primarily because high-pressure air was available for suit ventilation, but also because the cockpit was somewhat larger, improving mobility even further. The pilots suggested various improvements (many concerning the helmet

and gloves) after these flights, but overall the comments were favorable. The suit accumulated

[1061

8.25 hours of flight time during the tests.

The Aero Medical Laboratory advised the X-15 Project Office on 10 April 1958 that David Clark would deliver the first suit for Scott Crossfield on 1 June 1958. The laboratory cautioned, however, that the X-15 project would receive only four suits under the current contract. The laboratory would receive other full-pressure suits for service testing in operational aircraft, but these were not compatible with the X-15 cockpit. If additional suits were required, the X-15 Project Office would need to provide the Aero Medical Laboratory with additional funds.-107

Given the lack of funds for additional suits, the X-15 Project Office investigated the feasibility of using a seat kit instead of the back kit used on the first four suits. This would allow the use of suits designed for service testing, and allow X-15 pilots to use the suits in operational aircraft. The benefits of using a common suit would have been substantial, but by May 1958 it was too late since the X-15 design was too far along to change. Although the X-15 Project Office continued to pursue the idea, the X-15 suit remained different from similar suits intended for operational aircraft. The X-15 Project Office subsequently found funds for two more suits.108

On 3 May 1958, the configuration of the suit to be delivered to Crossfield was frozen during a meeting in Worchester among representatives of the Air Force, David Clark, and North American. The decision was somewhat premature since the suit configuration was still in question during a meeting three months later at Wright Field. This indecision had already resulted in a two-month delay, and the need for further tests was apparent.109

The X-15 Project Office advised the newly assigned chief of the Aero Medical Laboratory, Colonel John P. Stapp, that the suit delays might postpone the entire X-15 program. To maintain the schedule, the X-15 project needed to receive Crossfield’s suit by 1 January 1959, a second suit by 15 February, and the remaining four suits by 15 May. Simultaneously, the X-15 Project Office informed Stapp of the growing controversy concerning the use of a face seal (actually a separate oral-nasal mask inside the pressurized helmet) instead of the neck seal preferred by the Aero Medical Laboratory.119

North American believed the pilot should be able to open the faceplate on his helmet, using the face seal as an oxygen mask. The Aero Medical Laboratory disagreed. Since the engineers had long since agreed to pressurize the X-15 cockpit with nitrogen to avoid risks associated with fire, a neck seal meant that the pilot could never open his faceplate under any conditions. North American and the NACA had already ruled out pressurizing the cockpit with oxygen, for safety reasons. Eventually, the program adopted a neck seal for the MC-2 suit, although development of the face seal continued for the highly successful A/P22S-2 suit that came later.111

Crossfield finally received his MC-2 pressure suit on 17 December 1958. In a report dated 30 January 1959, the X-15 Project Office attributed much of the credit for the successful development of the full-pressure suit to Crossfield.117

David Clark tailored the resulting MC-2 suits for the individual pilots. Each suit consisted of a ventilation suit, upper and lower rubber garments, and upper and lower restraint garments. The ventilation suit also included a porous wool insulation garment. The edges of the upper and lower rubber garments were folded together three times to form a seal at the waist. The lower half of the rubber garment incorporated an anti-g suit that was similar in design to standard Air Force- issue suits and provided protection up to about 7 g. The X-15 provided gaseous nitrogen to pressurize the portion of the suit below the rubber neck seal. The suit accommodated in-flight medical monitoring of the pilot.117

The outer garment was not actually required for altitude protection. An aluminized reflective outer garment contained the seat restraint, shoulder harness, and parachute attachments; protected the pressure suit during routine use; and served as a sacrificial garment during high-speed ejection.

It also provided a small measure of additional insulation against extreme temperature. This was the first of the silver "space suits" that found an enthusiastic reception on television and at the movies.[114]

The X-15 supplied the modified MA-3 helmet with 100% oxygen for breathing, and the same source inflated the anti-g bladders within the suit during accelerated flight. The total oxygen supply was 192 cubic inches, supplied by two 1,800-psi bottles located beneath the X-15 ejection seat during free flight. The NB-52 carrier aircraft supplied the oxygen during ground operations, taxiing, and captive flight. A rotary valve located on the ejection seat selected which oxygen source (NB-52 or X-15 seat) to use. The suit-helmet regulator automatically delivered the correct oxygen pressure for the ambient altitude until the absolute pressure fell below 3.5 psi (equivalent to 35,000 feet), and the suit pressure then stabilized at 3.5 psi absolute. Expired air vented into the lower nitrogen-filled garment through two one-way neck seal valves and then into the aircraft cockpit through a suit pressure-control valve. During ejection the nitrogen gas supply to the suit below the helmet was stopped (since the nitrogen source was on the X-15), and the suit and helmet were automatically pressurized for the ambient altitude by the emergency oxygen supply located in the backpack.-1115

|

|

Here Scott Crossfield sits in a thermal-vacuum chamber during tests of a prototype XMC-2 (S794-3C) suit. These tests used temperatures as high as 165°F and the initial suits suffered from inadequate ventilation at high temperatures. Production versions of this suit were used for 36 early X-15 flights, and in a number of other high-altitude Air Force aircraft. (Boeing)

Despite the fact that it worked reasonably well, the pilots did not particularly like the MC-2 suit. It was cumbersome to wear, restricted movement, and allowed limited peripheral vision. It was also mechanically complex and required a considerable amount of maintenance. Nevertheless, there was only one serious deficiency noted in the suit: the oxygen line between the helmet and the helmet pressure regulator (mounted in the back kit) caused a delay in oxygen flow such that the pilot could reverse the helmet-suit differential pressure by taking a quick, deep breath. Since the helmet pressure was supposed to be greater than the suit pressure to prevent nitrogen from leaking into the breathing space, this pressure reversal was less than ideal, but no easy solution was available.-116-

Improved Girdles for the Masses

Fortunately, development did not stop there, and the first of the improved A/P22S-2 (David Clark Model S1023) full-pressure suits arrived at Edwards on 27 July 1959. The development by the David Clark Company of a new method to integrate a pressure-sealing zipper made it possible to incorporate all of the layers of the MC-2 suit into a one-piece garment, significantly simplifying handling and maintenance. A separate aluminized-nylon outer garment protected the suit and provided mounting locations for the restraint and parachute harness. A face seal that was more comfortable and more robust replaced the neck seal, which had proven relatively delicate and subject to frequent damage. A modified helmet mounted the oxygen pressure regulator inside the helmet, eliminating the undesirable time delay in oxygen flow. This time David Clark mounted the suit pressure regulator in the suit to eliminate some of the plumbing.-1117-

The consensus among X-15 pilots was that the A/P22S-2 represented a huge improvement over the earlier MC-2. However, it would take another year before the Aero Medical Laboratory delivered fully qualified versions of the suit to the X-15 program. By July 1960, the A/P22S-2 pressure suits started arriving at Edwards and familiarization flights in the JTF-102A began later in the year, along with additional X-15 cockpit mockup evaluations and simulator runs. North American also subjected the first suit to wind-tunnel tests in the company facility in El Segundo.-118-

Joe Walker made the initial attempt at using the A/P22S-2 in the X-15 on 21 March 1961; unfortunately, telemetry problems forced Walker to abort the flight (2-A-27). Nine days later Walker made the first flight (2-14-28) in the A/P22S-2. Walker reported that the new suit represented an improvement in comfort and vision over the MC-2. By the end of 1961, the A/P – 22S-2 had a combined total of 730 hours in support of X-15 operations; these included 18 X-15 flights, 171 flight hours in the JTF-102A, and 554 hours of ground time.-119-

The A/P22S-2 was clearly superior to the earlier MC-2, particularly from the pilot’s perspective. The improvements included the following:-120-

1. Increased visual area—The double curvature faceplate in the A/P22S-2, together with the use of a face seal in place of the MC-2 neck seal, allowed the face to move forward in the helmet so that the pilot had a lateral vision field of approximately 200 degrees. This was an increase of approximately 40 degrees over the single contoured lens in the MC-2 helmet, with an additional increase of 20 percent in the vertical field of view.

2. Ease of donning—The MC-2 was put on in two sections: the lower rubberized garment and its restraining coverall, and the upper rubberized garment and its restraining coverall. This was a rather tedious process and depended on folding the rubber top and bottom sections of the suit together to retain pressure. The A/P22S-2 was a one-piece garment with a pressure-sealing zipper that ran around the back portion of the suit and was zippered closed in one operation. It took approximately 30 minutes to properly don an MC-2; only 5 minutes for the newer suit.

3. Removable gloves—In the MC-2 the gloves were a fixed portion of the upper rubberized garment. The A/P22S-2 had removable gloves that contributed to general comfort and ease of donning. This also prevented excessive moisture from building up during suit checkout and X-15 preflight inspections, and made it easier for the pilot to remove the pressure suit by himself if that should become necessary. Another advantage was that a punctured glove could be changed without having to change the entire suit.

The A/P22S-2 also featured a new system of biomedical electrical connectors installed through a pressure seal in the suit, avoiding the snap-pad arrangement used in the MC-2 suit. The snap pads had proven to be unsatisfactory for continued use, since after several operations the snaps either separated or failed to make good contact because of metal fatigue. This resulted in the loss of biomedical data during the flight. In the new suit, biomedical data were acquired through what was essentially a continuous electrical lead from the pilot’s body to the seat interface.-1211

The number of details required to develop a satisfactory operational pressure suit was amazing. Initially the A/P22S-2 suit used an electrically heated stretched acrylic visor procured from the Sierracin Corporation. The visors were heated for much the same reason a car windshield is: to prevent fogging from obscuring vision. Unfortunately, on the early visors the electrical coating was applied to only one side of the acrylic and the coating was not particularly durable, requiring extraordinary care during handling. Polishing would not remove scratches, so the Air Force had to replace the scratched visors. David Clark solved this with the introduction of a laminated heated visor in which the electrical coating was sandwiched between two layers of acrylic. This required a new development effort since nobody had laminated a double-curvature lens, although a Los Angeles company called Protection Incorporated had done some preliminary work on the idea at its own expense. The David Clark Company supplied laminated visors with later models of the A/P22S-2 suit.1221

Initially, the MC-2 suit used visors heated at 3 W per square inch, but the conductive film overly restricted vision. The Air Force gradually reduced the requirement to 1 W in an attempt to find the best compromise between heating the visor and allowing unimpeded vision. Tests in the cold chamber at the Aerospace Medical Center during late January 1961 established that the 1-W visors were sufficient for their expected use.1231

Another requirement came from an unusual source. Researchers evaluating the effects of the high-altitude free fall during Captain Joseph Kittinger’s record balloon jump realized that the X – 15 pilot would need to be able to see after ejecting from the airplane. This involved adding a battery to the seat to provide electrical current for visor heating during ejection.-1124!

Like the MC-2 before them, the A/P22S-2 suits were custom made for each X-15 pilot, necessitating several trips to Worcester. It is interesting to note that although the X-15 pilots were still somewhat critical of the lack of mobility afforded by the full-pressure suits (particularly later pilots who had not experienced the MC-2); this was only true on the ground. When the suits occasionally inflated for brief periods during flight, an abundance of adrenaline allowed the pilot to easily overcome the resistance of the suit. At most, it rated a slight mention in the post-flight report.

As good as it was, the A/P22S-2 was not perfect, and David Clark modified the suit based on initial X-15 flight experience. The principle modifications included rotating the glove rings to provide greater mobility of the hands; improved manufacturing, inspection, and assembly techniques for the helmet ring to lower the torque required to connect the helmet to the suit, and the installation of a redundant (pressure-sealing) restraint zipper to lower the leak rate of the suit. Other changes included the installation of a double face seal to improve comfort and minimize leakage between the face seal and suit, and modifications to the tailoring of the Link – Net restraint garment around the shoulders to improve comfort and mobility. David Clark also solved a weak point involving the stitching in the leather glove by including a nylon liner that

Г1251

|

relieved the strain on the stitched leather seams.

|

The MC-2 suit led to the David Clark Company A/P22S suit that became the standard military and NASA high-altitude suit. The A/P22S and its variants have had a long career, and were used by SR-71 and U-2 pilots, as well as space shuttle astronauts. Here, NASA test pilot Joseph A. Walker

stands in front of an X-15 after a flight. (NASA)

Ultimately, only 36 X-15 flights used the MC-2 suit; the remainder used the newer A/P22S-2. Variants of the A/P22S-2 would become the standard operational full-pressure suit across all Air Force programs.

Post X-15

The X-15 was not the only program that required a pressure suit, although it was certainly the most public at the time. The basic MC-2 suit underwent a number of one-off "dash" modifications for use in various high-performance aircraft testing programs. Many of the movies and still photographs of the early 1960s show test pilots dressed in the ubiquitous aluminized fabric – covered David Clark MC-2 full-pressure suits.

The A/P22S-2 suit evolved into a series of variants designated the A/P22S-4, A/P22S-6, and A/P22S-6A (David Clark models S1024, S1024A, and S1024B, respectively) for use in most high – altitude Air Force aircraft, including the SR-71. Regardless of the success of the A/P22S-2 suit and its modifications for Air Force use, the cooperation between the Navy and Russell Colley at Goodrich continued. The Navy full-pressure suits included the bulky Mark I (1956); a lighter, slightly reconfigured Mark II; an even lighter Mark III (some versions with a gold lame outer layer) with an improved internal ventilation system; and three models of the final Mark IV, which went into production in 1958 as the standard Navy high-altitude suit.-1126!

The original Mercury space suits were reworked Mark IV suits that NASA designated XN-1 through XN-4, but the engineers usually referred to them as the "quick-fix" suits. The A/P22S-2 formed the basis for the Gemini suits, and ILC returned to the fray to produce the EVA suits used for Apollo. In March 1972, the Air Force became the lead service (the Life Support Special Project Office (LSPRO)) for the development, acquisition, and logistics support efforts involving pressure suits for the Department of Defense. This resulted in the Navy agreeing to give up the Mark IV full-pressure suit and adopt versions of the A/P22S-4/6. Today, the standard high-altitude, full- pressure suits used for atmospheric flight operations (including U-2 missions), as well as those used during space shuttle ascent and reentry, are manufactured by the David Clark Company.-1127!