DEVELOPING A CONSENSUS

The WADC evaluation of the NACA proposal arrived at ARDC Headquarters on 13 August. Colonel Victor R. Haugen, director of the WADC laboratories, reported that his organization believed the proposal was technically feasible. The only negative comment referred to the absence of a suitable engine. The WADC estimated that the development effort would cost $12,200,000 and take three or four years. The cost estimate included $300,000 for studies, $1,500,000 for design,

$9,500,000 for the development and manufacture of two airplanes, $650,000 for engines and other government-furnished equipment, and $250,000 for modifications to a carrier aircraft. Somewhat prophetically, one WADC official commented informally: "Remember the X-3, the X-5, [and] the X-2 overran 200%. This project won’t get started for twelve million dollars."-81

A four-and-a-half-page paper titled "NACA Views Concerning a New Research Airplane," released in late August 1954, gave a brief background of the problem and attached the Langley study as a possible solution. The paper listed two major problems: "(1) preventing the destruction of the aircraft structure by the direct or indirect effects of aerodynamic heating; and (2) achievement of stability and control at very high altitudes, at very high speeds, and during atmospheric reentry from ballistic flight paths." The paper concluded by stating that the construction of a new research airplane appeared to be feasible and needed to be undertaken at the earliest possible opportunity.-^

A meeting between the Air Force, NACA, Navy, and the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Development took place on 31 August 1954. There was general agreement that research was needed on aerodynamic heating, "zero-g," and stability and control issues at Mach numbers between 2 and 7 and altitudes up to 400,000 feet. There was also agreement that a single joint project was appropriate. The group believed, however, that the selection of a particular design (referring to the Langley proposal) should not take place until mutually satisfactory requirements were approved at a meeting scheduled for October.-101

Also on 31 August, and continuing on 1 September, a meeting of the NACA Subcommittee on High-Speed Aerodynamics was held at Wallops Island. Dr. Allen E. Puckett from the Hughes Aircraft Company was the chair. John Stack from Langley gave an overview of the proposed research airplane, including a short history of events. He reiterated that the main research objectives of the new airplane were investigations into stability and control at high supersonic speeds, structural heating effects, and aeromedical aspects such as human reactions to weightlessness. He also emphasized that the performance of the new airplane must represent a substantial increment over existing research airplanes and the tactical aircraft then under development. In response to a question about whether an automatically controlled vehicle was appropriate, Stack reiterated that one of the objectives of the proposed program was to study the problems associated with humans at high speeds and altitudes. Additionally, the design of an automatically controlled vehicle would be difficult, delay the procurement, and reduce the value of the airplane as a research tool.-11 design of the airplane" and that the establishment of a design competition was the most desirable course of action. The subcommittee forwarded the recommendation to the Committee on Aerodynamics for further consideration.-1121

Major General Floyd B. Wood, the ARDC deputy commander for technical operations, forwarded an endorsement of the NACA proposal to Air Force Headquarters on 13 September 1954, recommending that the Air Force "initiate a project to design, construct, and operate a new research aircraft similar to that suggested by NACA without delay." Wood reiterated that the resulting vehicle should be a pure research airplane, not a prototype of any potential weapon system or operational vehicle. The ARDC concluded that the design and fabrication of the airplane would take about 3.5 years. In a change from how previous projects were structured, Wood suggested that the Air Force should assume "sole executive responsibility," but the research airplanes should be transferred to the NACA after a short Air Force airworthiness demonstration program.-121

During late September, John R. Clark from Chance-Vought met with Ira H. Abbot at NACA Headquarters and expressed interest in the new project. He indicated that he personally would like to see his company build the aircraft. It was ironic since Chance-Vought would elect not to submit a proposal when the time came. Many other airframe manufacturer representatives would express similar thoughts, usually with the same results. It was hard to see how anybody could make money building only two airplanes.141

The deputy director of research and development at Air Force Headquarters, Brigadier General Benjamin S. Kelsey, confirmed on 4 October 1954 that the new research airplane would be a joint USAF-Navy-NACA project with a 1-B priority in the national procurement scheme and $300,000 in FY55 funding to get started.15

At the same time, the NACA Committee on Aerodynamics met in regular session on 4 October 1954 at Ames, with Preston R. Bassett from the Sperry Gyroscope Company as chairman. The recommendation forwarded from the 31 August meeting of the Subcommittee on High-Speed Aerodynamics was the major agenda item. The following day the committee met in executive session at the HSFS to come to some final decision about the desirability of a manned hypersonic research airplane. During the meeting, various committee members, including De Elroy Beeler,

Walt Williams, and research pilot A. Scott Crossfield, reviewed historic and technical data. Williams’s support was crucial. Crossfield would later describe Williams as "the man of the 20th Century who made more U. S. advanced aeronautical and space programs succeed than all the others together. He was a very strong influence in getting the X-15 program launched in the right direction." Williams would later do the same for Project Mercury.161

The session at the HSFS stirred more emotion than the earlier meeting in Washington. First, Beeler discussed some of the more general results obtained previously with various research airplanes. Then Milton B. Ames, Jr., the committee secretary, distributed copies of the NACA "Views" document. Langley’s associate director, Floyd Thompson, reminded the committee of the major conclusion expressed by the Brown-O’Sullivan-Zimmerman study group in June 1953: that it was impossible to study certain salient aspects of hypersonic flight at altitudes between 12 and 50 miles in wind tunnels due to technical limitations of the facilities. Examples included "the distortion of the aircraft structure by the direct or indirect effects of aerodynamic heating" and "stability and control at very high altitudes at very high speeds, and during atmospheric reentry from ballistic flight paths." The study admitted that the rocket-model program at Wallops Island could investigate aircraft design and operational problems to about Mach 10, but this program of subscale models was not an "adequate substitute" for full-scale flights. Having concluded that the

Brown group was right, and that the only immediate way known to solve these problems was to use a manned aircraft, Thompson said that various NACA laboratories had then examined the feasibility of designing a hypersonic research airplane. Trying to prevent an internal fight, Thompson explained that the results from Langley contained in the document Milton Ames had just distributed were "generally similar" to those obtained in the other NACA studies (which they were not), but were more detailed than the other laboratories’ results (which they were).[17]

Williams and Crossfield followed with an outline of the performance required for a new research airplane and a discussion of the more important operational aspects of the vehicle. At that point, John Becker and Norris Dow took over with a detailed presentation of their six-month study.

Lively debate followed, with most members of the committee, including Clark Millikan and Robert Woods, strongly supporting the idea of the hypersonic research airplane.

Surprisingly, Clarence L. "Kelly" Johnson, the Lockheed representative, opposed any extension of the manned research airplane program. Johnson argued that experience with research aircraft had been "generally unsatisfactory" since the aerodynamic designs were inferior to tactical aircraft by the time research flights began. He felt that a number of research airplanes had developed "startling performances" only by using rocket engines and flying essentially "in a vacuum" (as related to operational requirements). Johnson pointed out that "when there is no drag [at high altitude], the rocket engine can propel even mediocre aerodynamic forms to high Mach numbers." These flights had mainly proved "the bravery of the test pilots," Johnson charged. The test flights generated data on stability and control at high Mach numbers, Johnson admitted, but aircraft manufacturers could not use much of this information because it was "not typical of airplanes actually designed for supersonic flight speeds." He recommended that they use an unmanned vehicle to gather the required data instead of building a new manned airplane. If aeromedical problems became "predominant," Johnson said, a manned research airplane could then be designed and built, and it should have a secondary role as a strategic reconnaissance vehicle.[18]

|

|

Clarence L "Kelly"Johnson, the legendary founder of the Lockheed Skunk Works, was the only representative on the NACA Committee on Aerodynamics to vote against proceeding with the development of the X-15. Previous X-plane experience had left Johnson jaded since the performance of the research airplanes was not significantly advanced from operational prototypes. As it turned out, the X-15 would be the exception, since no operational vehicle, except the Space Shuttle, has yet approached the velocity and altitude marks reached by the X-15. (Lockheed Martin)

into flight research in the shortest time possible." In comparing manned research airplane operations with unmanned, automatically controlled vehicles, Crowley noted that the X-1 and other research airplanes had made hundreds of successful flights despite numerous malfunctions.-1191 In spite of the difficulties—which, Crowley readily admitted, had occasionally caused the aircraft to go out of control—research pilots had successfully landed the aircraft an overwhelming percentage of the time. In each case the human pilot permitted further flights to explore the conditions experienced, and in Crowley’s opinion, automated flight did not allow the same capabilities.-1291

After some further discussion, and despite Johnson’s objections, the committee passed a resolution recommending the construction of a hypersonic research aircraft:1211

ВЕЙОІЛЯЮЙ люга» ВТ NACA.

соиштёе oil ашфшамюэ, 5 ocrcam 1954

VKCREAS, The весе в з It/ of supremacy

In the air continues to place great urgency on solving the problems of flight with man-carrying aircraft at greater speeds and extreme altitudes, rth-i

МВДЩЦЗ, Ргордіа ion systems are now capable of propelling eufih aircraft to speeds and altlt^ea that Impose entirely new and unexplored aircraft design problems, and

WHEftEAS, It now appears feasible to construct a research airplane capable of initial eirploraticn of these problems,

HE ГГ HHtiW RESOLVED, That iJie Ccamlttee on Aerodynamics sudarses the proposal of the tetuadlata Initiation of a project to design and construct a research airplane capable of aohleving speeds of the order of №oh Number 7 and altitudes of several hundred thousand feet for the exploration of the problems of stability and control of maimed aircraft and aerodynamic heating In the severe form associated with flight at extreme speeds and altitudes.

The "requirements" of the resolution conformed to the conclusions from Langley, but were sufficiently general to encourage fresh approaches. Appended to the specification under the heading of "Suggested Means of Meeting the General Requirements" was a section outlining the key results of the Becker study.1221

Kelly Johnson was the only member to vote nay. Sixteen days after the meeting, Johnson sent a "Minority Opinion of Extremely High Altitude Research Airplane" to Milton Ames with a request that it be appended to the majority report, which it was.1231

On 6 October 1954, Air Force Headquarters issued Technical Program Requirement 1-1 to initiate a new manned research airplane program "generally in accordance with the NACA Secret report, subject: ‘NACA Views Concerning a New Research Aircraft’ dated August 1954." The entire project was classified Confidential. The ARDC followed this on 26 October with Technical Requirement 54 (which, surprisingly, was unclassified).1241

In the meantime, Hartley Soule and Clotaire Wood held two meetings in Washington on 13 October. The first was with Abraham Hyatt at the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) to obtain the Navy’s recommendations regarding the specifications. The only significant request was that provisions should exist to fly an "observer" in place of the normal research instrumentation package. This was the first (and nearly the only) official request from the Navy regarding the new airplane, excepting the engine. In the second meeting, Soule discussed the specifications with Colonel R. M. Wray and Colonel Walter P. Maiersperger at the Pentagon, and neither had any significant comments or suggestions.

With an endorsement in hand, on 18 October Hugh Dryden conferred with Air Force (colonels Wray and Maiersperger) and Navy (Admiral Robert S. Hatcher from BuAer and Captain W. C.

Fortune from the ONR) representatives on how best to move toward procurement. The parties agreed that detailed technical specifications for the proposed aircraft, with a section outlining the Becker study, should be presented to the Department of Defense Air Technical Advisory Panel by the end of the year. The Navy reiterated its desire that the airplane carry two crew members, since the observer could concentrate on the physiological aspects of the flights and relieve the pilot of that burden. The NACA representatives were not convinced that the weight and cost of an observer could be justified, and proposed that the competing contractors decide what was best.

All agreed this was appropriate. Again, the Air Force requested little in the way of changes.-1251

Hartley Soule met with representatives of the various WADC laboratories on 22 October to discuss the tentative specifications for the airplane. Perhaps the major decision was to have BuAer and the Power Plant Laboratory jointly prepare a separate specification for the engine. The complete specification (airplane and engine) was to be ready by 17 November. In effect, this broke the procurement into two separate but related competitions: one for the airframe and one for the engine.

During this meeting, John B. Trenholm from the WADC Fighter Aircraft Division suggested building at least three airplanes, proposing for the first time more than the two aircraft contained in the WADC cost estimate. There was also a discussion concerning the construction of a dedicated structural test article. It seemed like a good idea, but nobody could figure out how to test it under meaningful temperature conditions, so the group deferred the matter.

Also on 22 October, Brigadier General Benjamin Kelsey and Dr. Albert Lombard from Air Force Headquarters, plus admirals Lloyd Harrison and Robert Hatcher from BuAer, visited Hugh Dryden and Gus Crowley at NACA Headquarters to discuss a proposed Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for conducting the new research airplane program. Only minor changes to a draft prepared by Dryden were suggested.-261 The military representatives told Dryden that a method of funding the project had not been determined, but the Air Force and Navy would arrive at a mutually acceptable agreement for financing the design and development phases. During the 1940s and 1950s it was normal for the military services to fund the development and construction of aircraft (such as the X-1 and D-558, among others) for the NACA to use in its flight research programs. The aircraft resulting from this MoU would be the fastest, highest-flying, and by far the most expensive of these joint projects.

The MoU provided that technical direction of the research project would be the responsibility of the NACA, acting "with the advice and assistance of a Research Airplane Committee" composed of one representative each from the Air Force, Navy, and the NACA. The New Developments Office of the Fighter Aircraft Division at Wright Field would manage the development phase of the project. The NACA would conduct the flight research, and the Navy was essentially left paying part of the bills with little active roll in the project, although it would later supply biomedical expertise and a

single pilot. The NACA and the Research Airplane Committee would disseminate the research results to the military services and aircraft industry as appropriate based on various security considerations. The concluding statement on the MoU was, "Accomplishment of this project is a matter of national urgency."[27]

The final MoU was originated by Trevor Gardner, Air Force Special Assistant for Research and Development, in early November 1954 and forwarded for the signatures of James H. Smith, Jr., Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air, and Hugh L. Dryden, director of the NACA, respectively. Dryden signed the MoU on 23 December 1954 and returned executed copies to the Air Force and Navy.[28]

John Becker, Norris Dow, and Hartley Soule made a formal presentation to the Department of Defense Air Technical Advisory Panel on 14 December 1954. The panel approved the program, with the anticipated $12.2 million cost coming from Department of Defense contingency funds as well as Air Force and Navy research and development funds.-129

After the Christmas holidays, on 30 December, the Air Force sent invitation-to-bid letters to Bell, Boeing, Chance-Vought, Convair, Douglas, Grumman, Lockheed, Martin, McDonnell, North American, Northrop, and Republic. Interested companies were asked to attend the bidders’ conference on 18 January 1955 after notifying the procurement officer no later than 10 January. An abstract of the NACA Langley study was attached with a notice that it was "representative of possible solutions" but not a requirement to be satisfied.-129

|

|

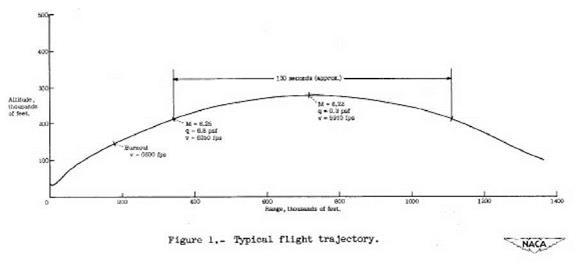

Also accompanying the invitation-to-bid letters was a simple chart that showed the expected flight trajectory for the new research airplane. It was expected that each flight would provide about 130 seconds of good research data after engine burnout. This performance was almost exactly duplicated by the X-15 over the course of the flight program. (NASA)

This was undoubtedly the largest invitation-to-bid list yet for an X-plane, but many contractors were uncertain about its prospects. Since it was not a production contract, the potential profits were limited. Given the significant technical challenges, the possibility of failure was high. Of course, the state-of-the-art experience and public-relations benefits were potentially invaluable. It was a difficult choice even before Wall Street and stock prices became paramount. Ultimately, Grumman, Lockheed, and Martin expressed little interest and did not attend the bidders’ conference, leaving nine possible competitors. At the bidders’ conference, representatives from the remaining contractors met with Air Force and NACA personnel to discuss the competition and

the basic design requirements. The list of participants read like a Who’s Who of the aviation world. Robert Woods and Walter Dornberger from Bell attended. Boeing sent George Martin, the designer of the B-47. Ed Heinemann from Douglas was there. Northrop sent William Ballhaus.-131

During the bidders’ conference the Air Force announced that each company could submit one prime and one alternate proposal that might offer an unconventional but potentially superior solution. The Air Force also informed the prospective contractors that an engineering study only would be required for a modified aircraft in which an observer replaced the research instrumentation, per the stated Navy preference. A significant requirement was that the aircraft had to be capable of attaining a velocity of 6,600 fps and altitudes of 250,000 feet. Other clarifications included that the design would need to allocate 800 pounds, 40 cubic feet, and 2.25 kilowatts of power for research instrumentation. A requirement that would come back to haunt the procurement was that flight tests had to begin within 30 months of contract award.