A Hypersonic Research Airplane

The 9 July 1954 meeting at NACA Headquarters and the resulting release of the Langley study served to announce the seriousness of the hypersonic research airplane effort. Accordingly, many government agencies and aircraft manufacturers sent representatives to Langley to examine the project in detail. On 16 July three representatives from the Air Research and Development Command (ARDC)-the Air Force organization that would be responsible for the development of the airplane-visited John Becker to acquaint themselves with the NACA presentation and lay the groundwork for a larger meeting of NACA and ARDC personnel.-11!

Independently of any eventual joint program, approval for the first formal NACA research authorization was granted on 21 July 1954. This covered tests of an 8-inch model of the Langley configuration in the 11-inch hypersonic tunnel to obtain six-component, low-angle-of-attack and five-component, variable-angle-of-attack (to about 50 degrees) data up to Mach 6.86.-12 Research authorizations were the formal paperwork that approved the expenditure of funds or resources on a research project. At the time, it was not unusual-or worthy of comment-for the NACA laboratories to conduct research without approval from higher headquarters or specific funding. This type of oversight would come much later.

During late July, Richard V. Rhode from NACA Headquarters visited Robert R. Gilruth to discuss the proposed use of Inconel X in the new airplane. Rhode indicated that Inconel was "too critical a material" for structural use, and the program should select other materials more representative of those that would be in general use in the future. Rhode later put this in writing, although Langley appears to have ignored the suggestion. This harkened back to the original decision that the research airplane was not meant to represent any possible production configuration (aerodynamically or structurally), but instead was to be optimized for its research role.-13!

|

|

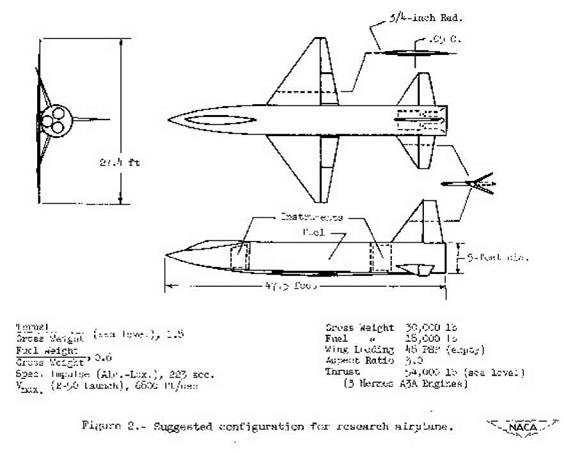

The overall configuration of the airplane conceived by NACA Langley in 1954 bears a strong resemblance to the eventual X-15. This configuration was used as a basis for the aerodynamic and thermodynamic analyses that took place prior to the contract award to North American Aviation. This drawing accompanied the invitation-to-bid letters during the airframe competition, although it was listed as a "suggested means" of complying with the requirements. (NASA)

On 29 July, Robert J. Woods and Krafft A. Ehricke from Bell Aircraft visited Langley as part of the continuing exchange of data with the industry. On 9 August, the Wright Air Development Center (WADC) sent representatives from the Power Plant Laboratory to discuss rocket engines, in particular the Hermes A1 that Langley had tentatively identified for use in the new research airplane. The WADC representatives went away unimpressed with the selection. The next day Duane Morris and Kermit Van Every from Douglas visited Langley to exchange details of their Model 671 (D-558-3) study with the Becker team, providing a useful flow of information between the two groups that had conducted the most research into the problem to date.^4-

The Power Plant Laboratory emphasized that the proposed Hermes engine was not a man-rated design, but concluded that no existing engine fully satisfied the NACA requirements. In addition, since the Hermes was a missile engine, it could only operate successfully once or twice, and it appeared difficult to incorporate the ability to throttle or restart during flight. As alternatives to the Hermes, the laboratory investigated several other engines, but suggested postponing the engine selection until the propulsion requirements were better defined.^5-

The Hermes engine idea did not die easily, however. As late as 6 December 1954, K. W. Mattison,^6 a sales engineer from the guided-missile department of the General Electric Company, visited John Becker, Max Faget, and Harley Soule at Langley to discuss using the A1 engine in the new airplane. Mattison was interested in the status of the project (already approved by that time), the engine requirements, and the likely schedule. He explained that although the Hermes engines were intended for missile use, he was certain that design changes would increase the "confidence level" for using them in a manned aircraft. He was not sure, however, that General Electric would be interested in the idea.[7]