Enter Howard Hughes

Enter Howard Hughes

Enter Howard Hughes

After Charles Lindbergh, and sharing fame with Amelia Earhart, Howard Hughes was America’s most famous aviator personality in the 1930s. He was admired by the public, respected by politicians who were aware of the power of his wealth, and recognized by the aviation community for his achievements. His wealth had been inherited from his parents who had died in the early 1920s, and at the age of 18 he began to expand the family business, the Hughes Tool Company, which held close to a monopoly of oil drilling bits.

Tlie Phenomenon

Taking to the business world like a duck to water—one commentator said that he ran his entire operation “out of his hip pocket for nearly 40 years”—he worked hard and played hard. He made films, including such epics as Scarface, Hell’s Angels, and The Outlaw. He romanced movie stars and flew airplanes. Everything he did was at the highest level of attainment, and this included his flying activities. Having won the Sportsman’s Trophy in 1934, he founded the Hughes Aircraft Company and built—and flew—a racing airplane, the H-l, and beat the world’s landplane speed record in 1935. The following year, in a Northrop Gamma, he broke the transcontinental speed record, and in 1937 broke it again, in his H-l. In this latter case, he flew at an altitude of 14,000 feet, using oxygen, and received the Harmon Trophy. In July 1938, in a Lockheed 14, he flew around the world in less than four days, averaging 202 mph. He had made meticulous preparations, and demonstrated systems of radio communication, weather reporting, and navigation that were in advance of their time. The aircraft was known as The Flying Laboratory,’ and for this flight, he received the Collier Trophy from President Roosevelt himself.

Into the Airline Fray

Howard came into the airline industry, therefore, with impressive credentials. By 1937, T. W.A. had passed out of the control by the Pennsylvania Railroad and North American Aviation (by the conditions of the 1934 Air Mail legislation) and was owned by Yellow Cabs’ John Hertz and Lehman Brothers, the investment bankers. T. W.A. President, Jack Frye, did not apparently like the control and approached Hughes with a view to starting another airline, which Hughes would finance and Frye would manage. Howard had another idea. In April 1939 he bought 25% of T. W.A. stock and by 1940 had increased this to a dominating 78%. He took over a great airline and set about the task of making it even better.

|

|

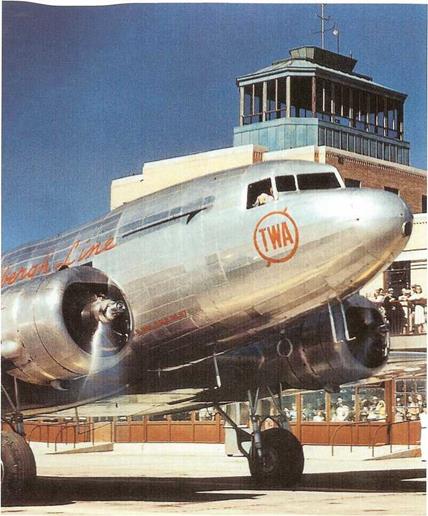

This picture epitomizes the tremendous impetus given to the United States airline industry during the latter 1930s. The busy scene can be contrasted with that of what was then a modern airport in the late 1920s (page 19), only a decade earlier. The DC-3 was truly the first transport airplane that could be called a modern airliner; and but for T. W.A. it might never have happened.