Heavy lifters

The Mil Mi-6

When, late in 1957, the Mil Mi-6 made its first flight, the reaction was justifiably one of awe. It was as long as an Ilyushin 11-18 and weighed almost as much. John Stroud, never inclined to use superlatives, described it as “truly enormous.” Each of the five rotor blades was 17m (55ft 9in) long, and, as with previous Mils, they had electro-thermal leading edge de-icing. Small, removable wings were fitted to the middle section of the fuselage. Two Soloviev D-25V turbine engines, rated at 5,500shp take-off power, enabled the Mi-6 to carry a load of 12,000kg (26,5001b) — this alone is the all-up weight of a DC-3.

Its rugged floor could accommodate trucks, drilling rigs, tanks, any large or bulky object. Its electric winch could handle a slung load of 9,000kg (almost ten tons) and in a firefighting role, it could carry 14,000kg (15 tons) of water. It was used almost exclusively in specialized air-lifting roles, but could carry 75 passengers if necessary. Deliveries began to Aeroflot in 1961, and it was first used in Turkmenistan on 10 August of that year. The airline had about 100 of these impressive aircraft by the late 1960s, and about half of these were allocated to the oil and gas fields of West Siberia.

|

(Above) The two-ton capacity crane inside the Mil Mi-26, for heavy-duty in the oilfields of the Tyumen region. (Below) A Mil Mi-10 (SSSR-04103), carrying a bus. (Vdovienko) |

|

|

The Mil Mi-10

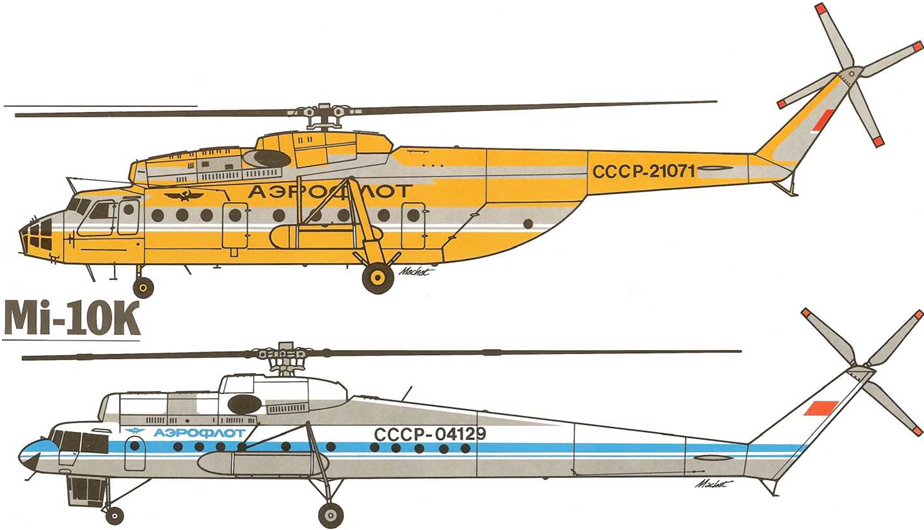

A direct development of the Mi-6, the Mil Mi-10 had the same enormous rotor and transmission, with a re-designed fuselage of about the same length, with long landing gear legs to make room for a platform underneath the fuselage and supported by hydraulic grips attached to the gear legs. If the Mi-6 could carry a small truck, the Mi-10 could carry a bus. To assist the crews in maneuvering at touch-down, the flight deck had closed circuit television monitors. The Mi-lOK (Korotkonogyi, or Short-Legged) version featured a special cabin under the nose, with rearward-facing controls for coordination with the winching crew. At Tyumen, base airfield for the region containing the world’s largest reserves of oil and gas, the demand is matched by the supply of helicopter strength (see page 77) of which the Mil Mi-lOs, fitted with both internal and external extra tankage, can carry out missions of up to 5 V2 hours duration. In the desolate areas of

Heroic Mission

If ever a case was to be made for the advantages of helicopter operations over those of fixed wing aircraft — and many were made in the U. S.S. R. in many diverse industrial activities, in the oilfields, the cotton fields, and the fishing grounds — it was made, under the most tragic circumstances, in 1986. On 26 April of that year, a nuclear reactor at Chernobyl, in the northern Ukraine, exploded with devastating effect, spreading a radioactive cloud over the area and for hundreds of miles around.

With a Hind military helicopter, with its gyro-stabilized gunsight, acting as a pathfinder for precise observation of the 1200°C ‘target’, the molten reactor, Mi-6s and Mi-26s plugged the lethal opening laid bare in the concrete structure. After several unsuccessful attempts to solve a problem that had a hundred unknown factors, by dropping graphite, sand/boron, gravel, lead composite, and concrete, the Mi-6s dropped a total of 250 tons of prefabricated 14-ton cubes, containing special filtering/ventilation units to shut off the radiation emission.

Ground staff, clad in lead-lined suits, and teams of helicopter pilots carried out this elaborate plan. The cost was high as everyone involved risked their lives by the deliberate exposure to the dangers of radiation. Many were affected and one, Anatoly Grishchenko, died as a result. But the reactor was capped, and the world breathed a sigh of relief.

Most of this brave work was performed by the Soviet Army’s helicopters, flown by some of the top test pilots. But Aeroflot played its part, supplying some observation Mi-6 and Mi-8 helicopters, and Antonov An-24s for inspection of the radiation-affected area.

taiga and tundra, with little surface communication, and opportunities for airfield construction rare, such vertical lift performance is priceless.

The Mil Mi-26

This development of the Mil Mi-6 also calls for superlafives. The Lotarev D-136 turbine engines develop ll,240shp, so as to drive on eight-bladed rotor (the Mi-6 had five). This enables the Mil Mi-26 to lift 20,000kg (20 tons). Inside the roomy fuselage — the size of that of a Lockheed C-130 — is a gantry crane able to carry two tons along the available space.

The Kamov Ka-32

While not aspiring to the dimensions of the mighty Mils, Kamov did not allow the grass to grow under its rotor blades. It produced, in the early 1980s, the Ka-32, a larger version of the multi-purpose Ka-26, about the same size and of the same capability and performance than the Mil Mi-8, but of the Kamov traditional technology and design, and with the advantage of two decades of developmental experience.

(Top) The supplementary control cabin of the giant Mil Mi-10. Rearward facing, the pilot has direct control of the helicopter, working in unison with the winch controller, (photos: R. E.G. Davies) (Bottom) This picture of the Kamov Ka-32 (with another hovering behind) illustrates the contrarotating rotorhead mechanism.

(V. Grebnev)

|

|

|

|

The dimensions and performance of these two large helicopters, together with those of the Mil Mi-26, are tabulated on page 75. Their size is dramatically illustrated by comparison with two well-known western fixed-wing aircraft on page 79.

(Right) This picture of the huge rotorhead of the Mil Mi-6, indicates the extent of the engineering of this large helicopter.

|

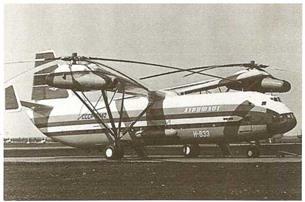

(Far right) The enormous Mil V-12 used two sets of Mi-6 engines, gearboxes and lifting rotors, mounted on stub wings. First flown in July 1968, it never entered seivice although it was extensively demonstrated in Aeroflot titles (photos: Boris Vdovienko)