ANT-25

Going For the Distance

For propaganda and prestige reasons alone, the goal of beating world records, especially in a technological field such as aviation, was attractive to the Soviet Union during the early 1930s. Andrei Tupolev realized that the existing long distance record was within its grasp, and obtained authorization from the Revolutionary War Council on 7 December 1931 to proceed with a new design, the ANT-25 RD (Rekord Dal’nost, or record distance). It was a carefully-fashioned product. The corrugated wing had an aspect ration of no less than 13-0, with fuel tankage distributed along the whole length, to relieve bending stress (later the corrugations were smoothed over with fabric, and the drag coefficient was reduced by 36 percent.) The fuel load was eventually increased to 6.1 tons, more than half the total gross weight of the airplane. Instrumentation included the first Soviet gyro-compass, a 500 W, 12 V generator, MF and HF radios, and a sextant in a hinged room station.

Mikhail Gromov made the first flight on 22 June 1933. After the modifications, a series of closed circuit flights in 1934 culminated in Gromov, with A. I. Filin and I. T. Spirin, setting a new world’s record on 10 September, at 12,411km (7,713mi) in a multi-lap triangular flight lasting 75hr 2min. Then, as preparations were made for a spectacular demonstration — trans-Polar flight — Gromov fell ill. In August 1935, the reputable Sigismund Levanevskiy flew towards the North Pole, but had to turn back (see opposite page); and that led to the critical meeting with Stalin. As the table below shows, the ANT-25 was in a great tradition of long-range specialist aircraft. And the honor of matching words with deeds fell to Valery Chkalov.

About 16 ANT-25s were built. No more recordbreaking flights were attempted, but the aircraft were used for experimental test flying.

Valery Chkalov, pilot of the fust trans-Polar flight of 1937.

Sigismund Levanevskiy, pilot of the third, and tragic attempt to fly across the North Pole in 1937.

In an amiable mood, the designer of the ANT-25, Andrei Tupolev, and Chkalov’s co-pilot, Georgy Baidukov, meet at Moscow airport in 1975. With them is General Bykov, Deputy Minister of Aviation, (photos: Boris Vdovienko)

|

The ANT-25 crew that flew from Moscow to California in 1937 (left to right) Danilin, Gromov, and Yumarshov. |

|

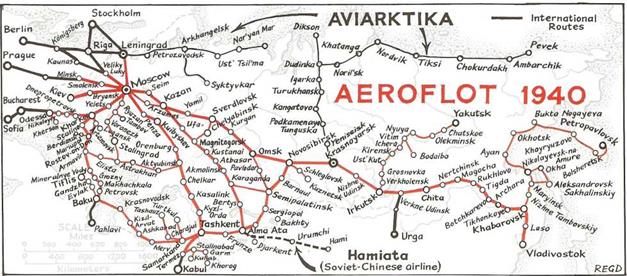

Aeroflot Consolidates

While all the headlines were being captured by Aviaarktika, with its brilliant support of the Papanin Expedition; by Chkalov’s and Gromov’s trans-Polar flights, and by Levanevskiy’s tragic disappearance; Aeroflot was building an air network, not so much by adding more routes (to those shown on the map on page 27) but by introducing better aircraft and more frequencies on the trunk lines and by adding small feeder services and bush routes to connect with the main arteries.

On 15 May 1937, for example, improved service from Moscow to Tashkent was announced, to augment the flights first started by Dobrolet in 1929, but which carried mainly mail and Pravda matrices. Rather as in the formative years of air transport in the United States in the 1920s, the passengers, mainly government officials, had lower priority. But from 1937 onwards, there was a distinct upgrading of service standards.

International Probing

The Prague route had opened, with PS-9 (modified ANT-9) service, on 31 August 1936, and following the demise of Deruluft on 31 March 1937, Berlin was added to the Aeroflot map. Service also started from Leningrad to Stockholm in 1937, but this was superseded — handsomely — on 11 November 1940, by a direct service from Stockholm to Moscow, via Riga and Velikie Luki. Operated jointly with the Swedish Airline A. B.A., both airlines used the Douglas DC-3; the Soviets, however, also flying the license-built Lisunov Li-2 version, production of which had begun in 1938, a contract having been made between Douglas and AMTORG (American Trading Organization) in August 1935 (see page 37). In an interesting preview of future events, the two airlines offered service from Stockholm (neutral during World War II) and Tokyo, via the Trans-Siberian Railway (interestingly, not by Aeroflot); while an even more ambitious connection was offered, from Scandinavia to San Francisco in 30 days, by Japanese ship from Kobe. This, of course, did not last very long.

Other indications of Aeroflot’s following the flag during this confused period of uncertain world politics were the opening of lines to Bucharest and Cluj, Romania, in 1938, and to Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1939. In that year also, a joint Soviet-Chinese air link was forged, from Alma Ata to Hami, in northwest China, the two points giving a name to the airline: Hamiata. But all hopes of further international expansion were dashed when Hitler’s Germany invaded the Soviet Union with Operation Barbarossa on 22 June 1941.

Gaining Stature

![]()

By 1940, the unduplicated mileage of Aeroflot’s route system was close to 100,000, and in that year it carried 350,000 passengers. The productivity, measured in passenger-miles flown, was 160 million. Aeroflot was now bigger than Deutsche Lufthansa, Europe’s biggest, and it was now the third biggest airline in the world.

By 1940, the unduplicated mileage of Aeroflot’s route system was close to 100,000, and in that year it carried 350,000 passengers. The productivity, measured in passenger-miles flown, was 160 million. Aeroflot was now bigger than Deutsche Lufthansa, Europe’s biggest, and it was now the third biggest airline in the world.

|

The Lights Co Out Again

Europe was an unsettled part of the world in 1938 and 1939. The seizure of Austria and the Sudentenland by Nazi troops had put every country on a war-alert footing. Old-style diplomacy had been replaced by a policy of might-is-right, and war seemed inevitable as Adolf Hitler pursued his insatiable desire for power. While some countries took defensive measures — France built its Maginot Line and Britain belatedly modernized its Royal Air Force — the U. S.S. R, disenchanted with trying to come to terms with the western democracies, signed a non-aggression pact with Germany — the infamous Molotov – Ribbentrop Pact — in August 1939. On 3 September, Germany invaded Poland, and the Second World War began. Echoing a famous phrase by British statesman Edward Grey in 1914, the lights went out in Europe once again.

Flight of the Moscow

Against the far-reaching political events, the world of commerce and culture, as always, carried on until the guns and torpedoes were actually fired. In the United States, New York was planning a spectacular World’s Fair, and rather surprisingly, the Soviet Union decided to mark the occasion by what was intended to be a spectacular airplane flight. Although the Chkalov and Gromov trans-Polar flights had been impressive, the disappearance of Levanevskiy had tarnished the image; and his death had further emphasized the severe dangers of

|

|

|

Vladimir Kokkinaki (photos: Boris Vdovienko) |

challenging the Arctic wastes.

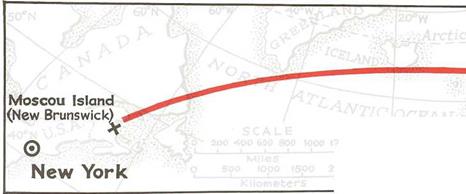

Accordingly, a shorter route was chosen, the Great Circle route westward from Moscow via Iceland and Greenland. The pilot was Brig Gen Vladimir Kokkinaki, flying an Ilyushin TsKB-30 (DB-3B) twin-engined bomber aircraft, the Moskva (Moscow), the same one in which he had made a nonstop flight to the Far East in June 1938. Accompanied by Major Mikhail Kh. Gordiyenko, he took off from Moscow on 28 April 1939, and then proceeded to face filthy weather, temperatures down to 54°C below zero, and, approaching the North American continent, dense fog. They lost their way and, with a certain amount of luck, managed to make a wheels-up forced landing in an ice-covered marsh on the little island of Miscou, New Brunswick, 6,250km (3,900mi) and 22hr 56min after leaving Moscow. They had actually flown farther, while they were lost, and made their landing with empty tanks.

|

Departure of the flight to Novaya Zemlya on 29 March 1936. Vodopyanov’s first segment, however, was only a few kilometers. |

Polikarpov R-5 (SSSR-N127), one of only two built, and in which Mikhail Vodopyanov made a flight to Novaya Zemlya in 1936.

Vodopyanov’s Shortest Hop

When the famous pilot Mikhail Vodopyanov set off on his epic survey flight of 29 March 1936, to determine if a route to the North Pole was feasible via selected locations in Novaya Zemlya and Franz Jozef Land (see page 28), he was given an enthusiastic send-off by a crowd of well-wishers at Moscow. He took off in a Polikarpov R – 5 (SSSR-N128), ostensibly en route to the Frozen North.

|

|

Little did the crowd know of a certain hesitancy in the hero Mikhail’s demeanour. For the day was a Sunday, and he was superstitious about flying on a Sunday. The first leg of his arduous route to the dreaded Franz Jozef Land was as short as he could make it — just over the rooftops and hedges to the nearest landing strip;, and out of sight of the adoring fans.