The Ranger Series

|

Fig. 10.1 The Ranger. Courtesy of NASA |

The Ranger Program was NASA’s first step in achieving President Kennedy’s goal of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely by the end of the 1960s. This long forgotten lunar probe program was initially a source of embarrassment to NASA and the nation, but eventually achieved its goals and paved the way for the Surveyor Program, followed then by the Apollo triumphs. The Ranger spacecraft mission evolved into a simple task: to take images of the lunar surface and return those images to Earth by a telemetry link until the Ranger spacecraft smashed into the Moon.

|

|

|

Fig. 10.3 LRO photo of the Ranger impact sites. Photo courtesy of NASA and Arizona State University |

In the scope of this book, consider visually locating the Ranger sites with a telescope as extra credit. LRO photos have located the Ranger impact sites with difficulty. Fortunately, the Apollo 12 landing site is not only within walking distance of Surveyor 3, but is also within the general area of the Ranger 7 impact zone. Apollo 11 also landed in the general vicinity of Ranger 8. To the backyard observer, basically locating Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 also encompasses the Ranger 7 and Ranger 8 impact zones. To locate the Ranger 9 impact site, first locate the major crater Ptolemy. The crater just south of Ptolemy is the crater Alphonsus, and Ranger 9 impacted just slightly north and east of the central peak within the crater.

The Ranger program was a series of unmanned lunar missions by NASA in the early 1960s whose design goal was to obtain the first close-up images of the lunar surface. The development of the basic Ranger spacecraft system began in 1959. The original concept for Ranger included a gamma ray spectrometer, radar altimeter, television imaging system, and a soft landing seismometer. These scientific equipment should sound familiar as parts of the eventual Apollo scientific equipment suites. The first six Ranger missions were complete failures, as NASA went through a learning process for developing space capable vehicles, space navigation, and launch technology and procedures. Ranger 1 and 2 were launch failures, and Ranger 3 and 5 totally missed the Moon. Ranger 4 impacted the Moon but experienced electronic systems failure. Ranger 6 impacted the Moon, but its cameras failed to function. At one point, the program was called "shoot and hope". After two congressionally mandated reorganizations of NASA and JPL, the Ranger program was stripped of much of its scientific equipment and simplified to its final kamikaze space camera configuration. Ranger 7 successfully returned images in July 1964, followed by two more successful missions.

The Ranger spacecraft had three different configurations.

• Block I, consisting of Ranger 1 and 2, were test missions. They were launched in 1961 for engineering development, and were not targeted for the Moon. The Ranger 1 spacecraft was designed to go into an Earth parking orbit and then into an extended elliptical Earth orbit to test systems and strategies for future lunar missions. Ranger 1 was launched into the Earth parking orbit as planned, but the Agena B booster stage failed to restart to put it into the higher trajectory, so when Ranger 1 separated from the Agena stage it went into a low Earth orbit and began tumbling. The satellite re-entered Earth’s atmosphere on August 30, 1961. The Ranger 2 followed a similar fate, and was launched into a low earth parking orbit, but an inoperative roll gyro prevented the Agena booster stage restart. As with its predecessor, Ranger 2 could not be put into its planned deep-space trajectory, and was stranded in low earth orbit upon separation from the Agena stage. The orbit decayed and the spacecraft reentered Earth’s atmosphere on November 20, 1961.

• Block II missions comprising of Ranger 3, 4, and 5, were launched during 1962 to achieve rough lunar landings, obtain science data, and test approach television camera operations. These Ranger spacecraft experienced satisfactory vehicle performance, but Ranger 3 missed the Moon by approximately 23,000 miles and Ranger 5 missed the Moon by about 450 miles. Ranger 4 suffered electronics problems that caused the solar panels to not open. Ranger 4 battery power failed after 10 hours and the probe was unable to perform mid-course corrections or activate its cameras. Ranger 4 impacted the Moon on the far side.

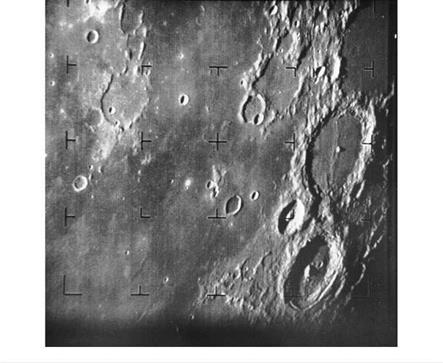

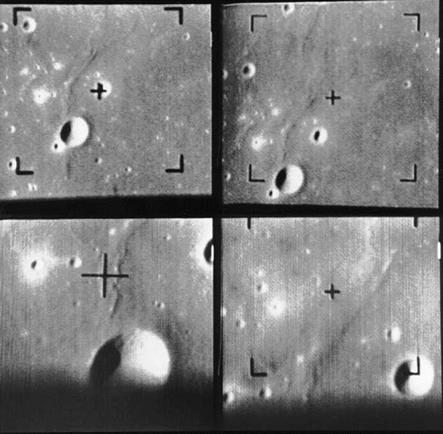

• Block III Missions were the Ranger 6, 7, 8, and 9 which used the experience of the earlier Ranger missions to achieve success in 1964 and 1965. NASA learned its lessons on navigating to the Moon and made technology modifications to enable transmission of high-resolution photographs of the lunar surface during the final minutes of flight. Ranger 6 performed satisfactorily en route to the Moon, but the camera failed to operate before lunar impact. Success finally came with Ranger 7, 8, and 9, as those missions fulfilled NASA objectives and provided more than 17,000 photographs at resolutions higher than ever achieved. The Ranger 7 and 8 missions provided coverage of the two types of mare terrain that included the area of the eventual Apollo 11 landing site. Ranger 9 provided coverage of the highland region, impacting in the large central highland crater Alphonsus.

The Ranger photographs provided valuable photographic information for future landing site selection for Surveyor and Apollo missions, and provided surface detail unavailable from Earth-based observations. Each Ranger spacecraft had 6 cameras on board. The basic cameras were the same with each camera set up for different exposure times, fields of view, lenses, and scan rates. The camera system was divided into two channels, P for partial and F for full, with each channel design having with independent power supplies, timers, and transmitters.

• The F-channel had 2 cameras: the wide-angle A-camera and the narrow angle B-camera. The final F-channel image was taken between 2.5 and 5 seconds before impact at an altitude of approximately 10,000 feet.

• The P-channel had four cameras: P1 and P2 (narrow angle) and P3 and P4 (wide angle). The last P-channel image was taken between 0.2 and 0.4 second before impact at an altitude of approximately 2,000 feet.

The images provided better resolution than was available from Earth based views by a factor of 1000. The smallest crater that earthbound telescopes could achieve was about the size of a large NFL or major college football stadium, while the images produced by the Ranger cameras showed from pickup truck sized craters down to the 1 feet sized features in Ranger 9 photos. These high resolution images showed Apollo mission planners that finding a smooth landing site was not going to be easy.

|

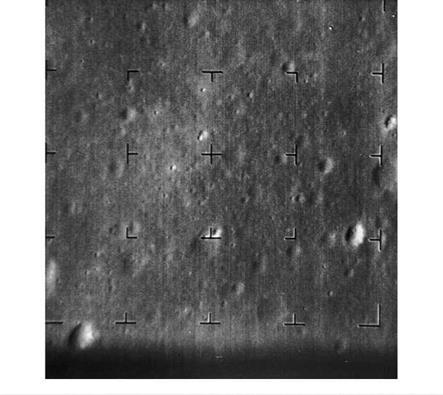

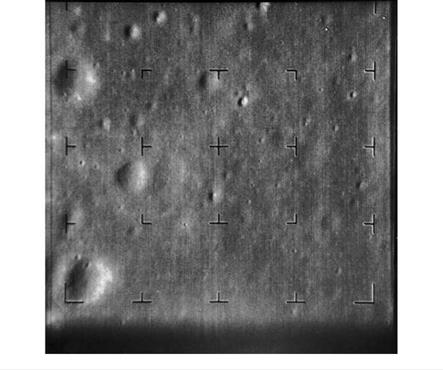

Fig. 10.4 Photo Sequence taken by Ranger 7 a camera approaching the Moon. Courtesy ofNASA |

|

Fig. 10.5 Courtesy of NASA |

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 10.8 Photo Sequence taken by Ranger 7 p camera approaching the Moon. Courtesy ofNASA |

|

Fig. 10.9 Courtesy of NASA |