PROGRESS М-55

Progress M-55 was launched from Baikonur, at 13:38, December 20, 2005 with 2,490 kg of cargo. The new spacecraft carried food, including 14 kg of fresh fruit and vegetables, water, oxygen, propellant, spare parts, and experiments for ISS. Progress docked to Pirs’ nadir automatically at 14:46, December 23. The crew began unloading the dry goods over the holiday week.

In the week running up to Christmas, McArthur and Tokarev performed experiments and recorded educational films. McArthur checked the hatch seals in the American modules of the station. The Christmas break represented the halfway point in their 6-month mission. On Christmas Day they were able to speak to their families, ate a traditional Russian meal, and opened the gifts that had been delivered on Progress M-55. They had a day off on December 26, and again on January 2, in keeping with standard American government employment rules that gave employees a day off in lieu when a national holiday falls on a Sunday. Meanwhile, Zvezda’s Elektron oxygen generator had been performing flawlessly since its last repair. It was deliberately shut down between December 28 and February 9, to allow the crew to burn Russian SFOG oxygen candles in order to re-certify that method of producing oxygen. On December 31, the last of the oxygen carried in Progress M-54 was used to re-supply ISS.

McArthur and Tokarev spent the first week of 2006 performing experiments, including the ground-commanded BCAT-3, placing the “phantom Torso’’ with its 370 radiation detectors in Pirs, and locating the EarthKam in one of the station’s windows in advance of the new school term. They also installed batteries in the American EMUs in Quest. January 9 was the final day of the Russian holiday and the crew had the day off. During the week, they installed the Recharge Oxygen Orifice Bypass Assembly (ROOBA), a method of allowing EVA astronauts to prebreathe oxygen from the Shuttle’s supply rather than the station’s tanks in Quest. Two days later the Elektron oxygen generator was powered on. On January 12, McArthur manoeuvred the SSRMS to provide views of the Interface Umbilical Assembly (IUA) on the S-0 ITS, which held the cable cutter for the MT’s uncut power cable. The following day he manoeuvred the SSRMS to view the CBM at Unity’s nadir and ensure that it was clear of debris. The SSRMS was left in a position where its cameras could view the crew’s up-coming EVA.

On the ground, the Houston marathon was taking place on January 15. In orbit, McArthur ran a half-marathon on the treadmill while ISS circled Earth. Over January 17-18, they rehearsed the procedures to be followed in the event of a rapid pressure leak requiring evacuation of the module in question. The following day, programme managers delayed the next EVA from February 2 to February 3, in order to ease the astronauts’ preparation schedule. The remainder of the week was taken up with both men performing experiments for their national programmes.

In the week commencing January 23, both men began preparing for their EVA. On January 31 they prepared an old Orlan suit, mounting a radio and slow-scan television transmitter on the helmet. The system transmitted messages in six languages that could be received by amateur radio operators. Now called “RadioScaf”, the suit had last been worn by Michael Foale in February 2004. It was filled with rubbish and would be jettisoned from ISS during the EVA. After preparing ISS for automated flight regime and shutting down the Elektron generator, the oxygen delivered in Progress M-55 was used to pressurise the ISS.

|

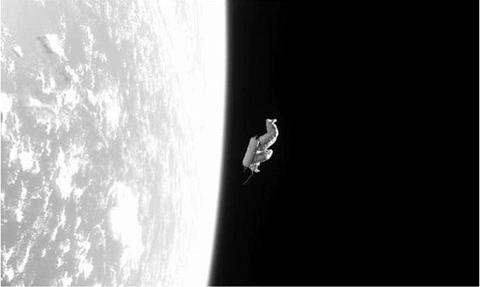

Figure 65. Expedition-12: A “past its sell-by date” Orlan pressure suit fitted with a radio transmitter was jettisoned to become a satellite in its own right. The experiment was named “RadioScaf”, but in their wisdom the media called it “Suitsat”. |

McArthur and Tokarev left Pirs wearing Orlan suits at 17:44, February 3. Having prepared their tools, they removed RadioScaf from the airlock and mounted it on a ladder on the exterior of the module, before releasing the suit into orbit with the words, “Goodbye, Mr. Smith,” from Tokarov. They photographed the suit as it drifted away. It transmitted its greeting messages for two orbits before the transmitter stopped working.

Moving away from Pirs, the two men made their way to the exterior of Zarya, where they removed a grapple fixture adapter for the Russian Strela crane and moved it to PMA-3, mounted on Unity. The adapter was removed to prepare Zarya for the temporary stowage of debris shields, prior to their deployment on a later Shuttle flight. Command of the EVA passed from Korolev to Houston as the astronauts passed from the exterior of Zarya on to the exterior of Unity. Next, they moved to the S-0 ITS, where they attempted to drive home a safety bolt in the cutting device in the IUA that McArthur had filmed on January 13. Despite several attempts with a high – tech tool, the safety bolt could not be installed to prevent the blade from falling and cutting the cable. Instead, as a temporary measure, McArthur removed the cable from the cutting mechanism and tied it to a handrail with a piece of wire. The cut cable on the other side of the ITS would be repaired during an EVA by the crew of STS-121. After transferring control of the EVA back to Korolev, the final task for this EVA was to photograph the exterior of Zvezda before returning to Pirs, where Tokarev recovered the Biorisk-2 experiment. The airlock hatch was closed after an EVA lasting 5 hours 43 minutes.

Two days later NASA Administrator Michael Griffin made a speech from NASA Headquarters, Washington, in which he stated:

The greatest management challenge the agency faces over the next five years is the transition from retiring the Shuttle to bringing the Crew Exploration Vehicle on-line… We are delving more deeply into the strategic implications of using Shuttle-derived launch systems for the Crew Launch Vehicle and Heavy – Lift Launch Vehicle… Thus, we are applying some funds from the exploration budget profile between now and 2010 to the Shuttle’s budget line to ensure the Shuttle and Station programmes have the resources necessary to carry out the first steps of the Vision for Space Exploration. NASA has asked industry for proposals to bring the CEV on-line as close to 2010 as possible, and not later than 2012 …’’

Griffin had initiated studies inside NASA to replace the Delta-IV and Atlas-V launch vehicles proposed for the CEV with a launch vehicle derived from proven Shuttle technology. Those studies would lead to the new Ares class of launch vehicles.

In the days following the EVA the crew took part in the standard debriefings with experts on the ground. McArthur also conducted a video tour of the station. The crew also continued their experiments; McArthur participated in the LOOT experiment, and Tokarev performed two ESA experiments. Both men performed Russian biomedical experiments and monitored the numerous experiments that ran automatically. They also gave the treadmill its 6-monthly overhaul. The motors in Progress M-55 were used to boost the station’s orbit on Lebruary 11. This was the first time that a Progress docked to Pirs had been used for an orbital re-boost. Over Lebruary 16-17, McArthur worked to replace the spectrometer inside the Mass Constituent Analyser (MCA) in Destiny. This measured the composition of the station’s internal atmosphere. An attempt to power the device up on the second day failed and McArthur was requested to perform troubleshooting.

As a new week began plans for the crew to “camp out’’ in Quest for their Lebruary 23-24 sleep period were delayed until March. The experiment called for the two men to spend a single sleep period in the airlock with the hatches sealed and the pressure reduced. Although they would not be wearing their EVA suits, the camp – out was seen as a way of reducing the pre-breathing of pure oxygen required before an extravehicular activity, by having future EVA astronauts spend their sleep period prior to an EVA camping out in Quest, and remaining in the airlock when they wake up, in order to don their EMUs and prepare for the EVA. The camp-out procedure would be used for the first time by EVA astronauts on STS-115. The delay was called as a direct result of McArthur’s failure to repair the MCA and, pending its repair, the camp-out was rescheduled for March 23.

McArthur and Tokarev began preparations for the next Shuttle flight, STS-121, now planned for no earlier than July 2006. McArthur made space in Destiny’s experiment racks for the equipment that Discovery would deliver to ISS. Both men worked to load Progress M-54 with additional rubbish, in preparation for its undocking planned for March 3. Meanwhile, on Lebruary 21, Progress M-55 performed a second re-boost manoeuvre. Progress M-54 was finally undocked from

|

Figure 66. Expedition-12: William McArthur works within the rear of an experiment rack inside Destiny. |

Zvezda’s wake at 06:06, March 3, 2006. Three hours later controllers in Korolev commanded it to re-enter the atmosphere, where it burned up over the Pacific Ocean. With the Progress gone, McArthur returned to his work on the MCA.

Meanwhile, on March 2, the programme managers from all of the ISS nations agreed a revised launch schedule to bring the station to “Core Complete’’, plus the International Partner modules before the Shuttle was grounded in 2010. The new schedule required 16 Shuttle flights, but almost as many Shuttle flights were wiped off the launch manifest. A number of Utility flights were removed, as were Russian plans to launch a smaller than originally planned MEM. The Americans would now supply additional electrical power to the Russian sector from the SAWs on the ITS, through 2015. The European and Japanese experiment modules were advanced, now launching in late 2007 and early 2008. Russian, European, and Japanese robotic cargo vehicles would now deliver many of the items originally scheduled to be launched on the cancelled Shuttle flights. NASA administrator Michael Griffin told reporters at KSC:

“The main thing you are seeing here today is the decision to put together an

assembly sequence that allows us to have very high confidence we will finish the

space station by the time the Shuttle must be retired… It’s the same station.

The end product is very much as we envisioned it.’’

McArthur completed proficiency training on the SSRMS on March 8. Over the next two days Controllers in Houston moved the SSRMS to view the IUA that had malfunctioned in December, cutting the back-up cable to the MT. They also viewed a valve on Destiny, looking for contamination. The valve was used to vent carbon dioxide overboard and appeared to be clean. This was the first time the SSRMS had been operated from the ground in an operational, rather than an experimental capacity.

The decision to retain Progress M-54 meant that Progress M-55 had had to dock to Pirs. The crew now had to move Soyuz TMA-7 back to Zvezda’s wake, thus allowing the Expedition-13 crew to dock Soyuz TMA-8 at Zarya’s nadir, where it would remain for the duration of their occupation. In the final hours of March 19, the Expedition-12 crew configured ISS for un-crewed flight and sealed themselves in Soyuz TMA-7. At 02: 49, March 20, Tokarev undocked the Soyuz from Zarya’s nadir and manoeuvred it to dock with Zvezda’s wake, at 03: 11. Korolev congratulated them for being the first crew to dock at all three Soyuz docking ports on ISS. The transfer was followed by a day of light duties, before the crew began reconfiguring the station for full occupation.

In March, a problem arose when blisters were found on EVA handrails during production on the ground. The blisters led to a questioning of the strength of the handrails on ISS and an instruction to only attach EVA tethers to the base of the station’s handrails, rather than the rail itself. Meanwhile, the crew spent time locating lithium hydroxide canisters to fit the Orlan EVA suits on ISS. New canisters would be launched on Progress M-56. They spent the remainder of their time on ISS preparing for the end of the Expedition-12 occupation, and their return to Earth. They also performed their last experiments. On March 29, they observed and photographed the total solar eclipse.

|

SOYUZ TMA-8 DELIVERS THE EXPEDITION-13 CREW

|

The Expedition-13 crew was launched in Soyuz TMA-8, at 21: 30, March 29, 2006. Korolev lost all telemetry links with the spacecraft for 10-15 minutes, shortly after it achieved orbit. The problem was caused by a communication outage with a Russian Molniya satellite. Onboard Soyuz TMA-8 all systems were performing as planned. The spacecraft docked to Zarya’s nadir at 23: 19, April 1. Following systems checks the hatches between the two vehicles were opened at 00: 59 the following day. Following the usual safety briefings Pontes transferred his couch liner from Soyuz TMA-8 to Soyuz TMA-7. He had trained for his flight as a temporary NASA astronaut, in return for an experiment rack to be mounted on the exterior of ISS. Budgetary difficulties prevented the Brazilians from producing the rack, but the flight of the Brazilian astronaut went ahead. In the next few days the two Expedition crews worked together to complete their hand-over while Pontes performed his own “Centenario” experiment programme. In all, Pontes completed 31 sessions with the 8 experiments, all in the Russian sector of the station.

Vinogradov was typically sincere in describing his duties as Commander of Expedition-13:

“[A]s the crew Commander, first and foremost I’m responsible for the safety of the crew, and my main task, the most important task is that we… return safe and sound back to Earth and have completed the flight program… The second thing is the state of the station. We understand that two or three of us are entrusted with the vehicle that’s valued at maybe hundreds of millions in dollars. It’s not even the question of its specific monetary value but tens of thousands of people worked on it and provided their labour and knowledge for its creation and we’re entrusted to control this complex setup. So that’s a responsibility that is quite significant for us, that we would not break anything or make it perform worse. So, that is quite a significant responsibility and that’s the second function of the crew Commander. The third important issue is our relationship as a crew, as a team. A small crew of two people creates a situation where even the smallest detail gains significant importance. Of course, spaceflight is different depending on its duration—during a short flight you can sort of do it as one feat, but a long spaceflight, you have to make sure that you pace yourself, that you distribute your strength evenly throughout the flight, and build the proper relationship with your crewmates. Even the smallest thing becomes quite important.”

He added:

“We will certainly be expecting the Shuttle and I’m hoping that it’s not going to be the only Shuttle that will visit us. Our task is to prepare the station to the maximum for the arrival of the Shuttle, and to be as effective as possible in terms of using the Shuttle flight… Those are our main tasks.’’

On April 3, McAthur and Williams “camped out’’ in the Quest airlock during their sleep period. Quest was isolated from ISS at 19: 45, and the pressure was lowered as planned. The two men began their sleep period, but 4 hours later they were woken by an error tone issued by software monitoring the atmospheric composition on ISS. Controllers in Houston decided to end the experiment at 01: 43, at which time the pressure was raised and the internal hatches opened.

The following day McArthur spoke to journalists during his preparations for return to Earth. He told them:

“By golly, it’s time to go home and spend some time with the family … It’s an absolute thrill and joy to live and work in space. But we miss the richness, the texture, the three-dimensional nature of living on our home planet. The coffee [on

|

Figure 67. Expedition-13: Pavel Vinogradov works on the lighting inside the Pirs airlock. |

ISS] tastes good, but it’s all in bags, and I’m really looking forward to smelling my cup of coffee. The next thing is food that crunches, like a good chef salad, and the sensation you get when you bite down of crunching into nice fresh lettuce or a raw carrot.’’

Earlier in the week Tokarev had commented, “We are ready to go home… We accomplished all of our tasks. We are happy, and we feel good.’’

Williams completed a training session with the SSRMS on April 5. He also received a briefing from McAthur on payload operations in Destiny. Meanwhile, Tokarev stowed equipment in Soyuz TMA-7 and reviewed undocking and re-entry procedures.

After a week of joint operations, Tokarev, McArthur, and Pontes sealed themselves in Soyuz TMA-7 for their return to Earth. Undocking occurred at 17: 28, April 8. TMA-7 landed in Kazakhstan at 20:48, after 189 days 18 hours 51 minutes in space. Pontes had been in flight for 9 days 21 hours 17 minutes. Following their recovery McArthur described re-entry for reporters, saying:

“It was wild ride, we loved it.’’

Talking about the end of his flight he added:

“I feel an overwhelming sense of satisfaction and maybe even closure… I have a little muscle and joint soreness, but I feel strong.’’

On his return to Houston, he told the crowd:

“There are a lot of people here I’ve known for a very, very long time. That is the thing I missed, family and close friends, and I look forward to spending time with all of them.’’