RETURN TO FLIGHT

From the moment that STS-107, Columbia, was lost, on February 1, 2003, NASA had been planning towards the Shuttle’s Return to Flight. NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe had immediately established the CAIB to identify the cause of Columbia’s loss and identify the actions NASA would be required to take before Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour could return to space. On July 28, 2003, O’Keefe also established the Return to Flight Task Group (RTFTG), to oversee NASA’s preparations for the Shuttle’s Return to Flight and the correct implementation of the CAIB’s recommendations. The CAIB published its report five weeks later, on August 26, 2003. It listed the 15 recommendations for the Shuttle’s safe return to flight contained earlier in this manuscript (see pp. 136-137).

Meanwhile, the loss of the second Space Shuttle orbiter with a full crew of seven astronauts had caused a re-think of America’s human spaceflight policy. On January 14, 2004, President George W. Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration. It called for the Shuttle’s Return to Flight and the completion of ISS to “Core Complete’’, with all American and International Partners’ modules in place. Additional Russian modules would be added as and when the Russian economy allowed. “Core Complete’’ was to be achieved in 2010, at which time the Shuttle fleet would be retired. NASA would develop by 2014 a new Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV), designed to act as a CTV and CRV for the station before returning humans to the Moon by 2020. In order to complete ISS by 2010, NASA would have to return the Shuttle to flight in 2005 and fly five successful missions per year for the next five years thereafter. It was a bold, if not impossible launch schedule. Despite all of their good words about the new priority to be given to crew safety to the media, NASA would have no choice but to be budget and schedule-driven.

Throughout 2004, NASA set a succession of target dates for the Return to Flight launch of STS-114, but they passed, one after the other, with no launch. Again and again the RTFTG reported to NASA Headquarters that the Administration was not sufficiently advanced on the CAIB’s 15 recommendations to attempt the launch. In January 2005, the RTFTG reported that NASA had still failed to meet 8 of the 15 recommendations. The following month Sean O’Keefe resigned as NASA Administrator. His position was filled by Michael Griffin, a former senior NASA engineer, on April 14, 2005.

By that time the STS-114 launch was set for May 15, and the vehicle was sitting on LC-39, Pad-B. Griffin delayed the launch and STS-114 was returned to the VAB, to have its ET and SRBs exchanged with those that had been delivered for the next

flight by Atlantis. The new ET contained anti-ice formation heaters that were part of the attempt by Lockheed-Martin to prevent foam and ice shedding from the ET during launch. STS-114 had originally been stacked to an ET that did not have these heaters.

The RTFTG final report Executive Summary was published on June 28; it stated that NASA had still failed to meet three of the CAIB’s recommendations for a safe return to flight. They had:

1. Failed to prove they had significantly reduced, or stopped foam and ice shedding from the ET during launch. NASA Administrator Michael Griffin had stated that the Administration might have to accept that it was impossible to stop all foam shedding from the External Tank.

2. Failed to harden the orbiter against strikes by foam and ice shed from the ET.

3. Failed to demonstrate heatshield tile repair methods and prove that repaired tiles could survive re-entry heating. (Ironically, STS-114 was due to demonstrate tile repair methods on deliberately damaged tiles carried into orbit for that specific purpose in the payload bay.)

STS-114 was moved back to the launchpad and prepared for launch on July 13. On that date the countdown was stopped at T — 2 hours when one of four fuel sensors malfunctioned. The launch was cancelled and an investigation began. Rather than replace the sensor, NASA informed the media that they fully understood the problem and would continue with the new launch if the exact problem was repeated during that attempt. Launch was set for July 26.

On July 18, Krikalev and Phillips tested the motion control system on Soyuz TMA-6. With Discovery’s launch delayed, NASA managers brought the transfer of Soyuz TMA-6 from Pirs to Zarya forward. The transfer was required so Pirs could be used as an airlock for an EVA by the Expedition-11 crew, originally planned for August. The transfer took place on July 19, with undocking from Pirs occurring at 06: 38. Krikalev backed the Soyuz away 30 m, flew laterally along the length of the station, and, after 14 minutes of station keeping, docking to Zarya took place at 07: 08. Fifty-two minutes later the crew entered ISS and began reconfiguring it for normal use. July 23, 2005, was the Expedition-11 crew’s 100th day in space. Having completed the packing of items for return to Earth on STS-114, they began to pack items for return to Earth on STS-121, due to fly in September 2005.

In advance of his present launch, Krikalev had said:

“We have a pretty well-developed process and pretty good calculations of how much water the human body consumes, how much food you need to continue operation on board the Station, and of course this kind of supply is first priority. That’s why, when Shuttle was not able to fly, all this kind of load was taken by Progress. But as a result we were not able to deliver as much equipment for scientific experiments. So increasing the variety ofmeans to deliver cargo on orbit increases not only amount of food (we don’t need food more than we can eat—we can increase our margins in case of emergency again, but we don’t need much more food than was delivered before), but we would be able to deliver more equipment for experiments. Returning [the] Shuttle back to flight would mean more scientific capabilities because we would be able to have three crewmembers after that. We would be able to conduct more experiments.”

Phillips was also looking forward to the Shuttle fleet returning to flight:

‘‘[S]ince the Columbia accident, the Russian Space Agency has been literally carrying the load and bringing us all the supplies we need, mostly on the Progress vehicle, [and] smaller amounts on the Soyuz vehicles. One impact of that is that we’ve only had a crew of two instead of a crew of three, which, of course, reduces the amount of science we can do. Another impact is that we’ve frankly been operating on pretty thin margins of certain consumables—food, water and oxygen. Once the Space Shuttles start flying, they carry a huge amount of mass to orbit, so they can bring our reserves of food, oxygen, and water back up to where they should be. The Shuttle makes water with its electrical power generation system [fuel cells]. We should get well with water, food and oxygen, as well as spare parts that we haven’t been able to bring back.

Another thing that people don’t often think of is the Shuttle also carries a tremendous amount of down-mass. We’ve been accumulating a lot of equipment, some of which is equipment that needs to be returned to Earth and some of which is just plain trash, and there are limited amounts we can get rid of on the Progress vehicles. We should be able to load some of that stuff on the Multi-Purpose Logistics Module that’ll be in the payload bay of the Shuttle, and help clean out the Station a little bit.’’

|

STS-114: A TEMPORARY RETURN TO FLIGHT

|

The STS-114 Return to Flight crew was made up of two pre-STS-107 crews. Lawrence, Thomas, and Camarda were assigned to the original STS-114 crew, which should have carried the original three-person Expedition-7 crew to ISS and returned the Expedition-6 crew to Earth. Collins, Kelly, Robinson, and Noguchi were the original STS-116 crew, which should have carried the original three-person Expedition-8 crew up to ISS and returned the Expedition-7 crew to Earth. The new STS-114 would retain much of the original flight’s logistics mission, carrying

|

Figure 58. STS-114 crew (L to R): James Kelly, Andrew Thomas, Wendy Lawrence, Charles Camarda, Eileen Collins, Soichi Noguchi. |

an MPLM to the station and a replacement CMG. For the first time the MPLM would be lifted out of the payload bay and returned to it using the SSRMS.

After a 2.5-year delay, STS-114 was finally launched at 10:39, July 26, 2005, and entered orbit a few minutes later. Throughout the launch over 100 high-resolution cameras filmed the ascent from all angles, in order to identify any debris that might shed from the vehicle. Noguchi used a hand-held video camera to film the ET as it was jettisoned. Before beginning their sleep period at 17: 00, the crew un-berthed the RMS and used its cameras to view the clearances between Discovery’s Ku-band antenna and the new Orbiter Boom Sensor System (OBSS) moored along the starboard sill of the payload bay.

Meanwhile, processing of the launch imagery showed a small piece of heatshield tile departing from close to Discovery’s nosewheel doors. A tile in that area had been damaged and repaired during vehicle preparation, and this repair may have been shaken loose during launch. At SRB separation, a large piece of debris was seen departing from the ET and moving away without striking the orbiter. Both events were videoed by new cameras mounted on the ET. Subsequent review of the images would show that the debris seen departing from the ET was the foam protuberance air load ramp: in short, it had the potential to fatally damage Discovery, just as the foam bipod ramp had doomed Columbia during the launch of STS-107. Only the airflow over the vehicle at SRB separation had prevented the large block of foam striking Discovery. Despite all of the work re-designing the area surrounding the bipod after STS-107, cameras revealed that a strip of insulation some 15 cm to 17 cm long had peeled away from the bipod itself. Also, two small dents were observed where the bipod ramp had been fitted up until STS-107. The dents should have been filled prior to the ET’s delivery to KSC, but apparently had not been, nor was the fact picked up during post-delivery inspections in the VAB, or during vehicle stacking and preparation for launch. On the subject of foam loss, NASA Administrator Michael Griffin said:

“Our guys are going to take a professional look at every frame of footage we have from every camera we have. These are test flights. The primary object under flight test is the external tank and all of the design changes we have made so we would not have a repeat of Columbia.”

Discovery’s crew were told of the two major debris-shedding events and that flight controllers would continue to review the various images at their disposal. Those images would ultimately reveal some 25 impacts on the orbiter during launch. Six areas would receive further inspection, including two regions where the felt-like material that was used to fill the gaps between the Shuttle’s tiles was seen to be protruding. It was feared that re-entering with the filler strips protruding might cause boundary layer turbulence and higher localised heating levels during re-entry if they were not removed.

Despite everything, shortly after achieving orbit, Collins paid respect to the seven astronauts lost on STS-107 saying, “We miss them, and we are continuing their mission. God bless them tonight, and God bless their families.’’ The crew began their 8-hour eat-sleep period just after 16: 00.

STS-114’s first full day in space began at 00:39. The crew downloaded their images of the ET separation. Kelly and Thomas activated the RMS, using it to pick up the OBSS, which was then employed to carry out a thorough laser-video scan of Discovery’s exterior, which was downloaded to Houston in its turn. Following the survey, the OBSS was re-berthed and the RMS cameras were used to video the Thermal Protection System on the crew compartment. With the external surveys completed the crew began preparations for docking with ISS by extending the docking ring and inspecting equipment that they would use during the closing manoeuvres. They also completed tests on the two EMUs that would be used during the mission’s three EVAs.

Flight Day 3 began at 23: 39, July 27. During the final rendezvous with ISS Collins slowed Discovery’s approach and performed a nose-over-tail pitch manoeuvre (official name: r-bar pitch manoeuvre) at a distance of 200 metres below the station. This allowed the Expedition-11 crew to obtain high-resolution digital photographs of Discovery’s underside. Docking occurred at 07: 18, July 28, by which time NASA had already announced that the remainder of the Shuttle fleet had been grounded indefinitely, as a result of the debris shed from STS-114’s ET during launch. Shuttle programme manager William Parsons announced, “Until we’re ready, we won’t go fly again. I don’t know when that might be.’’ He continued, “You have to

|

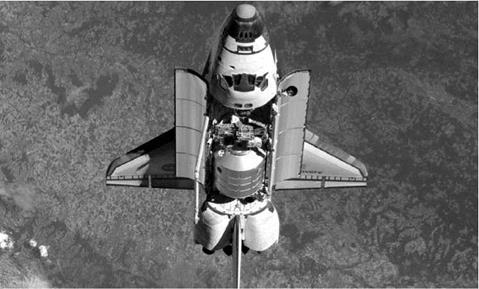

Figure 59. STS-114: as the first Shuttle flight after the loss of STS-107 three years earlier, STS – 114 performs the first r-bar pitch manoeuvre to allow the Expedition-11 crew to photograph the orbiter’s Thermal Protection System. The Multi-Purpose Logistics Module Leonardo is in the payload bay. |

|

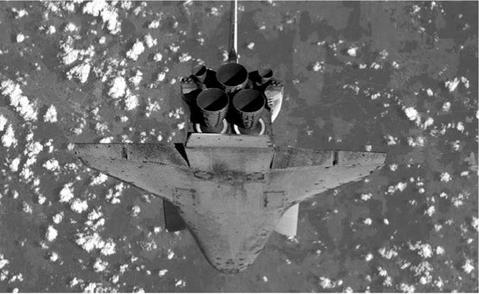

Figure 60. STS-114: the underside of the orbiter was photographed during the new r-bar pitch manoeuvre, to allow engineers in Houston to study the Thermal Protection System for damage incurred during launch. |

admit when you’re wrong. We were wrong… We need to do some work… foam should not have come off. It came off. We’ve got to go do something about that.’’

Following the usual greeting and safety brief, the two crews got to work carrying out additional inspections of Discovery. With the station structure obstructing direct use of the RMS, Kelly, Lawrence, and Phillips used the SSRMS to lift the OBSS from its storage location and hand it to Discovery’s RMS, which was operated by Thomas. The OBSS was then used to continue observations of the orbiter. Robinson and Noguchi spent time preparing for their three EVAs. After a joint meal both crews began their sleep period at 03: 40, July 29. While they were asleep mission control cycled Unity’s nadir CBM in anticipation of the following day’s activities.

The Shuttle crew were woken up at 23: 39, with the Expedition crew following at 00: 09, July 30. Following breakfast, Lawrence and Kelly used the SSRMS to grapple the MPLM Raffaello, lift it out of Discovery’s payload bay, at 02: 00, and dock it to Unity’s nadir. Electrical power from the station was applied to the MPLM at 08:50, and the hatches were opened to allow unloading to commence just after 10: 00.

In the meantime, Kelly and Phillips walked the SSRMS off Destiny and on to the MBS at 05: 39. They then used the arm’s cameras to provide situational awareness views of the survey that Camarda and Kelly would perform using the OBSS. Beginning at 07: 00, the latter pair used the OBSS mounted on Discovery’s RMS to view the six areas of special interest on Discovery’s heat protection system highlighted by Houston following review of the images already downloaded. Programme managers told the media that they were “feeling good about Discovery coming home.’’ Noguchi and Robinson continued to prepare their equipment for their first EVA, planned for July 30.

Discovery’s crew sealed the hatches between the two vehicles when they returned to the Shuttle for their sleep period. Before they went to bed they lowered the internal pressure to allow Noguchi and Robinson to acclimatise to the lower pressure at which their EMUs would operate. The air removed from Discovery was used to replenish the station’s atmosphere. Discovery’s crew were awoken at 23: 43, and after their breakfast they prepared for the first EVA. Noguchi and Robinson began their prebreathing of pure oxygen at 00: 39. At the same time Krikalev and Phillips walked the SSRMS off the MBS and back on to the exterior of Destiny, from where Lawrence and Kelly would operate it in support of the EVA.

The EVA began at 05: 46, July 30, when Noguchi and Robinson exited through Discovery’s airlock. Noguchi remarked, “What a view.’’ Robinson countered with, “There are just no words to describe how cool this is.’’

Once they were outside, Quest’s outer door was also opened to provide an emergency return to the station. Internally the hatches between Discovery and ISS had been closed while the two astronauts made their egress. They were now opened, to allow Collins and Camarda to transfer items between the two vehicles. During the EVA, Camarda also assisted Kelly in operating Discovery’s RMS, to use the OBSS to view seven areas of interest along the leading edge of Discovery’s port wing.

Having collected their tools, Noguchi and Robinson began a demonstration of how damaged heatshield tiles might be repaired on a future Shuttle flight. Working side by side, and using deliberately damaged tiles and RCC panels for the demonstration, one astronaut repaired damaged tiles using the Emittance Wash Applicator (EWA) while the other attempted to repair RCC panel samples using the Non-Oxide Adhesive Experiment (NOAX). With that important task complete they moved to the exterior of Quest, where they installed the External Stowage Platform-2 (ESP-2) Attachment Device (ESPAD) and associated cabling.

Noguchi’s next task was to replace a GPS antenna mounted on the ITS, which he completed without difficulty. Meanwhile, Robinson collected the tools they would require on their second EVA, and also re-routed electrical power plugs to direct power to CMG-2, which had been off-line since a circuit breaker had tripped in March 2005. Power flowed to CMG-2 at 10: 20, and controllers in Houston began the gyro’s spin-up to 6,600 revolutions per minute before bringing it back on-line as part of the ISS attitude control system. With time to spare at the end of the EVA, the two men recovered two long-term exposure experiments and photographed some disturbed insulation on the exterior of Discovery’s crew compartment. Quest’s hatch was closed, as were the internal hatches between Discovery and ISS, while Noguchi and Robinson returned to Discovery’s airlock. The EVA ended after 6 hours 50 minutes, at 12:36.

The day ended with Houston declaring Discovery’s tiles and thermal blankets fit to withstand re-entry. Their review of the RCC areas along the wings’ leading edges was still continuing. During the day Collins voiced her concerns over the foam shedding from the ET during launch saying, “Personally, I did not expect any large piece of foam to fall off the External Tank. We thought we had that problem licked.’’ During the day, the Shuttle’s flight had also been extended by 24 hours. The extension would allow for the transfer of more water and additional supplies, including two of the orbiter’s laptop computers, from Discovery to ISS, to support the new delay before the next Shuttle’s arrival at the station.

July 31 was a day of relatively light duties, including the transfer of equipment between the MPLM and the station, as well as interviews with journalists. Noguchi and Robinson reviewed plans for their second EVA, during which they would attempt to replace CMG-1, which had failed in June 2002, and had been off-line since that time. In preparation for the EVA, Lawrence and Kelly walked the SSRMS to the correct position on the exterior of Destiny.

Following their sleep period the crew were woken up at 23: 09, July 31, and began preparation for the EVA. Noguchi and Robinson opened Discovery’s airlock hatch at 04: 42, August 1, and set about preparing their tools. Meanwhile, controllers in Houston had turned off the electrical power to CMG-1. Both men made their way hand over hand to the Z1 Truss, on Unity’s zenith, where Noguchi mounted the work platform on the end of the SSRMS, which was operated by Lawrence and Kelly. During the ride out to his work place Noguchi remarked, “Oh, the view is priceless. I can see the moon.’’ The two men removed CMG-1, and Noguchi held it in his arms while he was manoeuvred down to Discovery’s payload bay. Robinson also made his way back to the payload bay. There, Noguchi temporarily stowed the old CMG while its replacement was removed from a crate and then replaced by the old unit. Noguchi held the replacement CMG-1 while he was manoeuvred back up to the Z1-Truss, where he waited for Robinson to arrive. The two men then worked to install the new

|

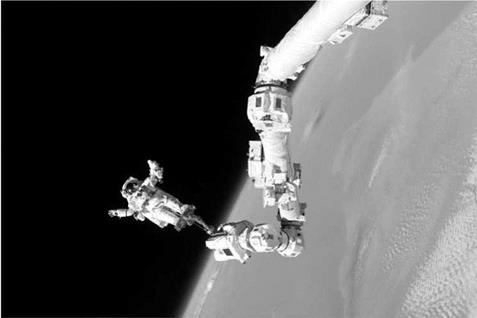

Figure 61. STS-114: Robinson rides the SSRMS during the night’s second extravehicular activity. |

CMG. With the installation complete, the new CMG-1 was spun up and, after several hours of monitoring, brought on-line as part of the station’s attitude control system. Discovery’s hatch was closed at 11:56, after an EVA lasting 7 hours 14 minutes. The remainder of the day was spent transferring equipment and rubbish between the two spacecraft.

On the ground, Flight Director Paul Hill described the new attitude for keeping the crew informed on the state of their spacecraft:

“Our intent is never to hide the state of the vehicle from the crew. But has our threshold changed for TPS damage assessment? You bet it has. There are some things that we are significantly smarter on today than we were two and a half years ago, and I don’t know how we could be in any different place today, since we all know that TPS damage cost the lives of the last crew.’’

On August 2, Houston gave permission for Robinson to venture beneath Discovery and attempt to remove, or cut away the two protruding gap fillers during the third EVA, planned for the following day. The crew spent the day preparing for this additional task, which included Lawrence and Kelly practising the intended SSRMS manoeuvres using software carried in one of the station’s laptops. To make time for Robinson to work with the gap fillers, Lawrence and Kelly used the SSRMS to unstow the EPS-2 from its position in Discovery’s payload bay. This had originally been included in the timeline for the third EVA.

Following another sleep period, the Shuttle crew were awoken at 23: 09, August 2. Noguchi and Robinson exited Discovery’s airlock at 04:48, August 3, to begin their third EVA. Their first task was to make their way to the ESPAD that they had installed on the exterior of Quest during their first EVA. Lawrence and Kelly then manoeuvred ESP-2 into position on the ESPAD using the SSRMS. With the ESP secured in place the SSRMS was walked off Destiny and on to the MBS, mounted on the ITS.

Noguchi installed the MISSE-5 exposure experiment and removed the Rotary Joint Motor Controller from the ITS and placed it in storage. In the meantime, Kelly and Camarda used Discovery’s RMS, with the OBSS still attached, to view the tile and RCC repair experiments that Noguchi and Robinson had completed during their first EVA. With his tasks completed Noguchi moved over to offer whatever support he could to Robinson in his final task. Robinson mounted the SSRMS and was manoeuvred beneath Discovery’s nose, where he was easily able to pull the two protruding “gap fillers’’ out from between TPS tiles. Robinson told Houston, “It looks like the big patient is cured!’’ With that task complete, Noguchi and Robinson returned to Discovery’s airlock and sealed the hatch at 10:49, after 6 hours 1 minute of exposure to space.

Following their hectic schedule, August 4 was planned as a relatively easy day. Lawrence and Kelly walked the SSRMS off the MBS and back to the exterior of

|

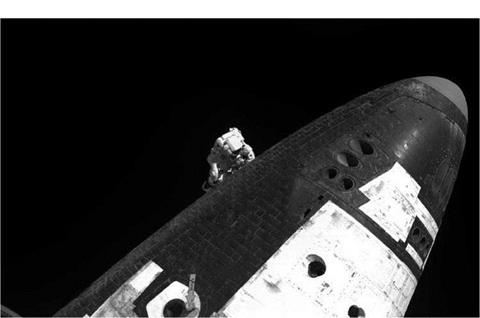

Figure 62. STS-114: in an unanticipated activity Stephen Robinson extracted two “gap fillers’’ from the underside of the Shuttle’s nose. |

Destiny. They then attached the free end to Raffaello, in advance of its undocking. Noguchi spoke to the Japanese Prime Minister by video link and the American astronauts received a call from President Bush, who told them:

“I just wanted to tell you all how proud the American people are of our astronauts. I want to thank you for being risk-takers for the sake of exploration. And I wish you Godspeed in your mission. I know you’ve got very important work to do ahead of you. We look forward to seeing the successful completion of this mission. And obviously, as you prepare to come back, a lot of Americans will be praying for a safe return.’’

A day of more equipment stowage was followed by a joint meal and a commemoration of the STS-107 crew. During the day the Shuttle’s crew paid their respects to the American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts who have been lost in the exploration of space. Lawrence remarked:

“Even if the future is equally unimaginable to us, we can be sure that future generations will look upon our endeavours in space as we look upon those early expeditions across the seas. To those generations, the need to explore space will be as self-evident as the need previous generations felt to explore the Earth and the seas.’’

Krikalev and Phillips ended their day by preparing Unity’s CBM for Raffaello’s undocking, before both crews went to sleep in their respective spacecraft.

Discovery’s crew was woken up at 22: 15, August 4. Kelly and Lawrence used the SSRMS to undock Raffaello from Unity’s nadir, at 07:34, August 5. Raffaello now contained 3,175 kg of items dating back to Expedition-6, the last Expedition crew to be supported by a Shuttle flight. With the MPLM secured in Discovery’s payload bay at 10: 03, Camarda and Thomas joined Kelly and Lawrence to locate the OBSS along the starboard payload bay door sill. The remainder of the day was spent stowing equipment on Discovery’s mid-deck. Both crews went to bed at 14: 09.

Awake again at 22: 09, the two crews shared a farewell ceremony for the leaving visitors at 00: 36, August 6. Discovery’s crew returned to their spacecraft and the hatches were sealed at 01 : 14. Kelly was at the controls when Discovery undocked, at 02: 24, and moved away to a distance of 122 m. He began a fly-around manoeuvre at 03: 54, and finally manoeuvred clear of ISS at 05: 09. The crew were given the remainder of the day as free time, going to sleep at 00: 39, August 7. The ISS crew went to bed at 14: 09.

Discovery’s crew were woken up at 20: 39, and spent much of their work day stowing equipment for re-entry. The one remaining question was the area of TPS below Collins’ window which had been under review since it was first seen in video footage. Julie Payette called from Houston to say, “We have good news. The MMT just got to the conclusion that the blanket underneath… the window is safe for return. There is no issue.’’ During the day, Collins, Kelly, and Robinson tested Discovery’s aerodynamic surfaces and fired the orbiter’s thrusters. The day ended at 12:39, August 7. Meanwhile, the Expedition-11 crew spent a quiet day and adjusted their schedule back to their normal routine. They were woken up at 02: 00, August 7.

Discovery’s crew began August 7 by waking up at 20: 39. They commenced their final preparations for the de-orbit burn and re-entry. The crew had two opportunities to land in the pre-dawn darkness at KSC, at 04:47 or 06: 22, August 8, but Discovery was waved off for 24 hours, due to unpredictable weather. Following the wave-off, Discovery’s engines were fired at 08: 19 to optimise the landing opportunities on August 9. The crew’s day ended at 00: 39, August 9.

Up at 08: 39, the crew repeated their final preparations for re-entry, going through the checklist once again. All three landing sites, KSC, Florida, Edwards Air Force Base, California, and White Sands, New Mexico, were activated for this second attempt to land. Meanwhile, the world’s media were baying like dogs, waiting for Discovery to burn up, so they could repeat their tired calls for the space programme to be cancelled. Persistent thunderstorms over Florida led to the two KSC landing opportunities being cancelled. Discovery would now land in California. Travelling with its three SSMEs forward, Discovery’s thrusters performed retrofire at 07 : 06. Turning, the orbiter assumed the usual nose forward and high position for reentry. Collins brought the flight to a successful close, gliding Discovery to a perfect landing at Edwards Air Force Base in the pre-dawn darkness, touching down at 08: 11.

Krikalev and Phillips sent their congratulations from ISS, but the successful landing meant that the Shuttle fleet was now grounded once more.

In her post-landing speech Collins remembered the crew of STS-107 once more:

“Today was a very happy day for us, but we have mixed feelings. We have very bittersweet feelings as we remember the Columbia crew… I thought about them the whole mission—what their experiences were. The Columbia crew believed in what they did, they believed in the space mission. I know if they were listening to me right now, they’d want us to continue this mission.’’

NASA Administrator Michael Griffin reminded the media at a press conference a few days later, when the crew returned to JSC in Houston:

“For two-and-a-half-years we have been through the very worst that manned spaceflight can bring us. Over the last two weeks, we have seen the very best.’’

He continued:

“Essentially, this was a test flight. It has provided data that we can use going forward. The bad news is there were three or four things we didn’t get. The good news is we hugely reduced any damage to the orbiter through the engineering measures we took to improve the tank. We specifically said the return to flight test sequence was two test flights. We plan for the worst and we hope for the best and that’s how we conduct business.’’

Collins was more personal when she spoke to the engineers who had returned the Shuttle to flight,

“Getting the Shuttle flying again was difficult work, but it was a labour of love. Words cannot describe how much my thanks go out to you for putting your heart and soul into what you believe.”