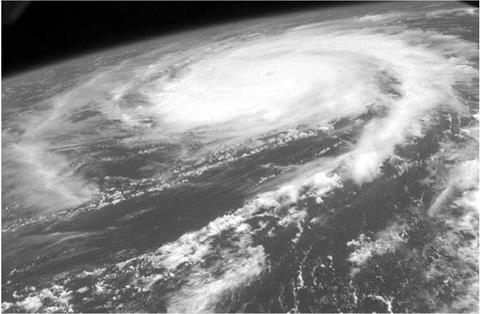

HURRICANE FRANCIS VISITS CAPE CANAVERAL

Fincke had reported photographing Hurricane Francis over the Atlantic Ocean on August 27. The hurricane passed over Kennedy Space Centre on September 7, with winds of 70 mph. Those winds pulled approximately 820 panels off of the side of the VAB along with the insulation beneath them, leaving the building interior open to the weather. The building’s roof proved to be weakened when it was inspected after the storm and nets were hung inside the building to catch any falling debris until the roof could be repaired. The two Shuttle ETs and various SRB components inside the VAB were not damaged. The roof was also partially ripped off a building used to prepare heatshield tiles for the Shuttle, but the three remaining Shuttle orbiters were secured within the three Orbiter Processing Facility Buildings and were not damaged. Only one month earlier, Hurricane Charley had caused $700,000 worth of damage to Cape Canaveral, and Hurricane Ivan, one of the most powerful hurricanes on record, also threatened to add to the damage at the site, until it changed course and missed Florida.

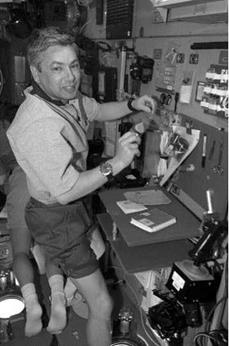

The highlight of September 3 came when Padalka and Fincke donned their Orlan pressure suits and depressurised Pirs for their final EVA. Egress occurred at 12: 43. Having gathered their tools, the two men made their way to the exterior of Zvezda, where they replaced a flow regulator valve panel and installed three communication antennae at the station’s wake. The antennae would be used during rendezvous and docking of the European ATV. Fincke made his way across the exterior of Zvezda to photograph the Japanese MPAC/SEEDS experiment. Upon returning to Pirs they

|

Figure 46. Expedition-9: Gennady Padalka wears a Russian Orlan suit during the Expedition-9 crew’s third two-man extravehicular activity. |

|

Figure 47. Expedition-9: Hurricane Francis was observed from ISS during Expedition-9. |

installed covers on the handrails around the airlock hatch to prevent EVA astronauts’ tethers becoming ensnared during future EVAs. Pirs’ hatch was closed at 18:04, after and EVA lasting 5 hours 21 minutes.

The Elektron unit failed during the night of September 6-7. The new failure involved the unit’s hydrogen gas analyser and had nothing to do with the ongoing problem of air in the water loop. On September 8, Padalka replaced one of the Elektron liquid units with one he had repaired using spare parts. The crew then flushed the Elektron through with water, cleaned a mounting plate and, after it had shut itself down several more times after only short periods of operation, they removed the gas analyser. The unit was then turned on and run for a few days. It was turned off once more before the crew went to sleep on September 17. On the ground engineers began studying the data relayed from the partially repaired unit. Korolev announced that the latest failure may have been caused by crystalline deposits of potassium hydroxide in the oxygen supply line of the liquid unit. While the Elektron was turned off, the station’s atmosphere was repressurised using oxygen carried into orbit on Progress M-50 and nitrogen from the tanks on Quest.

Even as repairs to the Elektron unit continued, on September 17 Fincke depressurised the area between the window panes in Destiny and replaced the flex hose, which had malfunctioned and allowed air to enter the space between the panes of glass. He also installed a cover that he had made previously at the workbench in Destiny. They tested the communications systems in the Soyuz TMA-4 spacecraft and Fincke videoed those areas of the station’s exterior that were visible from windows in the various modules and transmitted the images to Earth.

During the week ending September 24, Padalka and Fincke performed the regular 6-month preventative maintenance of the station’s treadmill. They also continued to troubleshoot the Elektron oxygen generator, working on the assumption that the hydrogen line was being prevented from pressurising correctly by contamination in the line. During the week, the two crewmen cleaned out the line in question. Meanwhile, the station’s atmosphere was repressurised twice, using oxygen from the tanks in Progress M-50. The crew also began storing some items for their return to Earth during the second week of October. On the ground, NASA had begun talking publicly about evacuating ISS, if the onboard stock of breathing oxygen fell below 45 days.

The Elektron repairs continued into October. Under instruction from Korolev, the crew disconnected the unit’s hydrogen vent pipe from its overboard vent valve, and Padalka jury-rigged a hose to redirect the vented hydrogen through Zvezda’s micro-purification unit. The unit then operated correctly during several days of testing. Fincke also fitted a mass spectrometer unit to the Major Constituents Analyser in Destiny. Progress M-50 had delivered the mass spectrometer, and its installation allowed the Analyser to be operated continually, rather than only periodically, as it had been up until that time. During the week, Fincke also carried out a series of soldering experiments. Engineers in Houston carried out a remote test of the Thermal Radiator Rotary Joint, which would allow the radiator to rotate to the best position for loosing heat when more SAWs were added to the station, after the Shuttle resumed flying, probably in 2005. Alongside the numerous equipment repairs, regular maintenance, and daily exercise, the crew still found time to perform a number of experiments on themselves.

As their flight approached its end, during the second week of October both men donned their Sokol launch and re-entry suits and entered Soyuz TMA-4 for routine checks. Fincke replaced the gas trap and pump inlet filter in the still malfunctioning EMU. He also replaced the cycle ergometer control panel with one that had been brought up on Progress M-50. Both men collected samples of potable water for in – flight analysis.

|

SOYUZ TMA-5 DELIVERS THE EXPEDITION-10 CREW

|

In March 2004 the Russians had suggested to NASA that the Expedition-10 crew should double the standard 6-month Expedition crew duration to one year. Such a flight would build on Russian medical experiments from their Salyut and Mir stations. It would also clear a second couch in Soyuz “taxi” spacecraft to be sold to visiting astronauts. NASA refused the proposal, after heated debate. While some NASA employees argued that the Administration was not ready to support a 12-month flight, others pointed to Russia’s experience on Mir, when several cosmonauts had approached 12-months in space and a few had surpassed it. Despite the discussions, Expedition-10 would fly a standard 6-month caretaker mission. Chiao described the role of a two-person caretaker crew in the following terms:

“[I]t is a very demanding timeline for a crew of two, and the past two-person crews have shown that they can accomplish those timelines and remain healthy and well-rested and things like that. [O]ur flight will be the same… and we have a very full schedule; we’ll be doing a lot of work. But at the same time, we’ll be having scheduled time off, where we can kind of re-energize and recharge, and so I really don’t see a problem with that. Now, of course, the thing that suffers sometimes when we are scheduled in like this, is we don’t get as much science done as we’d like. The purpose of the International Space Station is to do all kinds of cutting – edge science that can’t be done on the ground, but our goal right now is to kind of keep that laboratory going… until we can get the Shuttle flying again and… we get the laboratory finished… Neither Salizhan nor I have flown a long-duration flight; however, between us, we have four Shuttle flights, and so we have a wealth of experience being in space and operating in space. We work very well together; our personalities complement each other, and we both have the same views on how things ought to be done. And so I think that everything will be just fine.’’

The third couch on Soyuz TMA-5 became available when prospective spaceflight participant Sergei Polonsky was grounded for unspecified medical reasons. Unable to sell it at short notice to another spaceflight participant, to ESA, or to the French National Space Agency, the Russian Federal Space Agency allocated it to Yuri Shargin, a member of the Russian Rocket Forces, who would complete the usual short visit to ISS, returning to Earth with the Expedition-9 crew.

On September 15 the Russians announced that the launch of Soyuz TMA-5, which had been scheduled to lift off on October 9, had been delayed for 5 to 10 days. The cause of the delay was the premature firing of an explosive bolt on the spacecraft. The few details announced at the time suggested that the bolt was one of those used to separate the orbital compartment prior to re-entry. The Russians subsequently announced that it was actually one of a ring of bolts used to separate the docking system from the front of that compartment in the event of the docking system failing to release as the spacecraft tried to undock from ISS. In that event the spacecraft’s docking system could be explosively severed and left attached to the station’s docking system while the Soyuz returned to Earth. On September 22 the launch was reset for October 11. Six days later the launch was delayed a second time “for a few days’’. RSC Energia officials did not release details of what had caused the delay, but it has been suggested that it was a leaking membrane in a hydrogen peroxide tank. The launch was rescheduled to October 13.

Soyuz TMA-5 lifted off at 23:06, October 13, 2004. A communications problem involving a Russian Molniya satellite delayed each of the first two orbital correction burns by one orbit. Two days later, as the Soyuz approached within 100 metres of the station, an alarm sounded suggesting that the Kurs automatic rendezvous and docking system had malfunctioned. A Russian investigation would show that a forward firing thruster on the Soyuz was producing less thrust than expected and Soyuz TMA-5 therefore approached ISS too fast, causing the docking attempt to be aborted. Sharipov assumed manual control, backed his spacecraft out to 200 metres and then executed a perfect manual docking at 00: 16, October 16, thereby earning himself a bonus. Following leak checks the Expedition-10 crew entered ISS at 03: 13, and was greeted by their predecessors. Shargin transferred his couch liner to Soyuz TMA-4.

For the next week Sharipov and Chiao spent 2 or 3 hours a day working closely with Padalka and Fincke to ensure a smooth hand-over, the remainder of the time they spent setting up their own experiment programme. During the hand-over period Sharipov assisted Padalka in making final repairs to the Elektron unit before it was powered on during the hours the crew was awake, and powered off while they were asleep. Meanwhile, Chiao and Fincke worked to replace the rotor pump in the EMU that Fincke had begun repairs on a few days earlier. The new crew also took the opportunity to gain hands-on experience with the SSRMS and several of the ISS systems. Shargin participated in a number of medical experiments, with assistance from Sharipov and Padalka. He also took a number of photographs of the Earth’s surface. Although Shargin was the first member of the Russian Rocket Force to fly in space, none of his experiments was identified as military in nature. He completed his experiment programme, primarily in the Russian sector of the station.

|

Figure 49. Expedition-10: having arrived with the Expedition-10 crew, Yuri Shargin worked on his experiment programme before returning to Earth with the Expedition-9 crew. The individual behind him is not identified.

Figure 49. Expedition-10: having arrived with the Expedition-10 crew, Yuri Shargin worked on his experiment programme before returning to Earth with the Expedition-9 crew. The individual behind him is not identified.

Fincke had described his feelings on returning to Earth before his flight began:

“For the return, I’ll be the Flight Engineer, sitting in the left seat, pushing all the buttons, and Gennady will have his command panel in front of him. [W]e’ll work together as a team to bring… the ship safely home… We do all of our systems checks, and if everything looks good and we have concurrence from the ground, we undock from the Space Station—some springs push us off, and we’re on our way home. It’s going to be a very bitter-sweet moment. I’ll be so excited to go home and see my family… so, that’ll be the sweet part. The bitter part is leaving our home for six months. And, it’ll all happen in just a few hours. We make sure we have a successful undocking from the Space Station, we wait one orbit to upload our commands from… Moscow, who gives us all of our vectors so that we can come in and land right on target. [0]nce we get the ‘go’, we start our de-orbit burn; it slows us down by several hundred meters per second. Then… we… enjoy the ride. I think it’s going to be very… exciting just watching to see if anything goes wrong and to be there ready to solve any malfunction. And once we start to get close to the atmosphere, we’ll separate all three modules… Then the real fun begins. The other Americans that have flown in the Soyuz… have called it an incredible ride because we tumble end-over-end until we stabilize in the atmosphere. And I’ll be sitting right next to a window, and I’m just looking forward to seeing what that would look like. 0nce we stabilize in the atmosphere, the automatic re-entry system engages and brings us close to our point, and then we have a set of primary parachutes that will open up and slow us down. And then right before we land … a series of retro-rockets ignite and soften our blow as we return home to the planet. We open up the door and, hopefully, the helicopters will be outside waiting for us.’’

Following an official hand-over on October 22, Padalka, Fincke, and Shargin locked themselves in Soyuz TMA-4, and undocked from Zvezda’s wake at 21:08, the following day. After retrofire, and a routine separation, Soyuz TMA-4 re-entered the atmosphere and landed at 20:36, the same day. Locally it was dawn, and recovery crews had seen the plasma sheath surrounding the re-entry module as it passed through the atmosphere. The landing took place in semi-darkness. The Expedition-9 crew had spent 187 days 21 hours 17 minutes in space. Shargin’s first spaceflight had lasted 9 days 21 hours 21 minutes.

As October drew to a close NASA announced that the Shuttle’s Return to Flight launch would slip until May or June 2005.

EXPEDITION-10

Following the departure of Soyuz TMA-4 Sharipov and Chiao began the standard 3 days of light duties to allow them to get over the rushed workload of the past week. Their occupation would receive two Progress cargo vehicles and they planned to make two Stage EVAs before Soyuz TMA-6 delivered the Expedition-11 crew, in

April 2005. The new crew activated EarthKam during the first days of their occupation. In 8 days over 800 images were exposed. At the outset of their mission, word was received from the ground that the Elektron unit was performing well in tests and was cleared for permanent use. The joint repairs carried out by Padalka and Sharipov had finally returned the unit to operational use.

On November 4, Chiao used the Advanced Ultrasound in Microgravity experiment (ADUM) to make ultrasound scans of Sharipov and the positions were reversed the following day. The experiment relayed the scan directly to doctors on the ground, who could use it to make a real-time diagnosis. On November 5, both men took part in emergency medical drills and collected air and swab samples in Zarya. Chiao used the BCAT experiment. He also practised using the SSRMS on November 8. During the exercise the arm’s video cameras were used to image a possible indentation that had been observed on the exterior of Destiny by the last Shuttle crew to visit ISS (STS-113). The images proved that the dent was not caused by a micrometeorite, or a debris strike. The flat area on one of Destiny’s protective panels appeared similar to flat areas observed on the protective exterior of Unity. The flattening of the panels was thought to be caused by flexure with changes in temperature.

Throughout the week, the two men carried out work with the Binary Colloids Alloy Test (BCAT) experiment. Chiao also worked on the faulty pump in the second of the American EMUs that had suffered a cooling failure during the Expedition-9 occupation. The work had to stop when a metal shim could not be located. Following a search, plans were put in place to launch a replacement on Progress M-51. The American EMUs were not due to be used until the Shuttle resumed flight, in mid-2005.

Chiao explained how he and Sharipov had trained to receive STS-114 during their occupation of ISS:

“That’s something we’re hoping for—we’d love to have STS-114 come up and visit us during our flight. [W]e’d welcome them and well, we’re keeping our fingers crossed. It’ll be a really neat event having the Space Shuttle return to flight and come up during our increment and do some construction work while we’re there, and our two crews will work together, and we sure hope that’ll happen.. .we have been doing the training for these events. Salizhan and I have both received MPLM training and we also received a lot of photography lessons on how to take pictures of the Shuttle tiles and leading edges to inspect the heat shielding. [S]o we’re just keeping our fingers crossed it’ll work out for 114 to come up.’’

On November 8, NASA announced that they had initiated a study to consider how best to continue development of ISS after the Shuttle resumed flying. At the same time, they confirmed that the Shuttle’s return to flight had been delayed from March to May 2005. Bill Readdy, Associate Administrator for Space Operations, told the media, “After four hurricanes in a row, we could not make the March launch.’’ The new schedule called for three Shuttle launches in 2005 and five each year thereafter, until ISS was complete and the Shuttle was retired, in 2010. Readdy stated that, if the first two daytime Shuttle launches were successful, then the third

|

Figure 50. Expedition-10: Salizhan Sharipov floats inside Zvezda wearing his Sokol launch and re-entry suit. |

flight might carry the first three-person Expedition crew to ISS since the loss of STS-107. To cover the continued delay in the Shuttle’s Return to Flight, Russia agreed to continue supplying Soyuz TMA spacecraft for crew transport through 2006. This was a negotiated agreement that allowed Russia to recover the experiment hours it had given up to NASA in the early years of the programme when Zvezda was under-funded and launched late. Twenty-eight Shuttle flights were considered necessary to complete ISS. Studies considered transferring as many as 17 ISS payloads to expendable launch vehicles, leaving only 11 Shuttle flights. Among ideas being considered was a plan to launch the European Columbus and Japanese Kibo modules on Russian Proton launch vehicles. Initial development of the CEV design was underway in a multi-contractor competition.

On November 11, a circuit breaker tripped out on ISS and stopped the supply of electrical power to a number of crew equipment items. After checking the equipment involved the crew were able to power the circuit breaker back on. The following day, Chiao moved the SSRMS to a position that allowed its cameras to view the transfer of Soyuz TMA-5 from Pirs’ nadir to Zarya’s nadir, a manoeuvre planned for November 29. The change of location would allow Pirs to be used for two Stage EVAs, in January and March 2005.

The following week, controllers in Korolev commanded Progress M-50’s rocket motors to fire, to raise the station’s orbit. Although the burn lasted the correct amount of time, it left the station in a slightly lower orbit than had been planned.

Controllers at Korolev later blamed the shortfall on “human error”. Rather than fire a correction burn, it was decided to delay the launch of Progress M-51 by 24 hours to compensate for the station’s lower orbit. Throughout the week, the crew completed a varied science programme. Working with the American ADUM and Serial Network Flow Monitor (SNFM), which used computer software to track the communications and data flow between payloads in Destiny. Sharipov collected samples for the PLANT experiment and worked with the Russian experiments Hematokrit, which counted red blood cells, and Sprut, a study of human body fluids. Sharipov also checked out a new Russian Orlan suit before discarding an old Orlan suit that had exceeded its on-orbit life, on Progress M-50. Both men also participated in routine housekeeping tasks.

A NEW RUSSIAN LAUNCH SCHEDULE

On November 20, managers at Roscosmos decided to develop the FGB-2 module as a Multi-purpose Laboratory Module (MLM), rejecting RSC Energia’s proposal to develop the FGB-2 as the Enterprise Module. RSA announced that MLM would be launched by a Proton launch vehicle in 2007 and would dock to Zarya’s nadir, the European Robotic Arm would then be attached to its side. The MLM would be launched with some scientific equipment pre-installed, but the remainder would be launched separately over the following 2 years. It would also house support equipment, hygiene facilities, a sauna, and an additional sleeping room, as well as a storage area to hold spare parts and other cargo on-orbit. An aft docking port would support Soyuz and Progress vehicles, while a lateral port would house a scientific airlock, to be delivered by Shuttle.

The next major Russian launch would be the Scientific Energy Module (Russian initials: MEM), originally called the Scientific Energy Platform (Russian initials: MEP). This would be mounted on Zvezda’s Zenith after delivery by Shuttle in 2010. The new MEM would be downsized from the original MEP and would consist of a pressurised section containing gyrodines, a boom, and eight SAWs. The pressurised section would provide a new docking location for Pirs, which would be moved from its present location on Zarya’s nadir port by means of the SSRMS.

Plans were less substantial and less certain for a Russian dedicated science module using the FGB design, due for launch in 2011. It would be docked to Zvezda’s nadir and two smaller Russian scientific modules built around the Pirs design.

Meanwhile, Energia unveiled plans for the Soyuz replacement, a 13-tonne spacecraft to be called “Kliper”. The lifting body design of the re-entry module would be enhanced by a Soyuz-style orbital compartment and would carry six people. Uncrewed flight-tests on a Zenit launch vehicle were planned for 2010, with the first crewed flight to ISS in 2012. Again, no government funding existed for Kliper and attempts to convince ESA to help fund its development were unsuccessful.

While the plans sounded optimistic, there was no budget to build any of this equipment. Russian participation in the ISS programme would remain restricted to those modules already in orbit and any Soyuz and Progress vehicles that were

purchased, either by the Russian government or the other ISS partners in support of the Expedition crews throughout the life of the station, which was originally intended to end in 2016.