IN ORBIT, LIFE GOES ON

On August 1, Korzun and Whitson moved the SSRMS so that the camera on its end- effector could view the MBS and the attached POA grapple fixture that was mounted there. The POA was commanded to go through the motions of grasping a payload while being filmed. The controlling computer placed the POA in “Safe Mode’’ when data suggested that the motors were running too fast. The equipment was powered off and then powered on once more before re-running the test with the POA’s motor running more slowly. The test was completed without further problems. During the day Progress M-46’s rocket motors were used to boost the station’s orbit and place ISS in the best orbit to support the arrival of the next Progress and the Soyuz TMA-1 exchange flight. Whitson also repositioned the SSRMS to a location where its cameras could be used to view the EVA planned for August 16.

All three astronauts spent the following week preparing for their first Stage EVA. They also found the time to follow a set of instructions read up from the ground that allowed them to complete a temporary repair on their malfunctioning treadmill. The repair allowed them to use the treadmill in an un-powered mode until the part for a repair could be delivered on the next Progress, to be launched on September 20. During the week, the Russians announced that Soyuz TMA-1 would be launched on October 28.

The first of two Expedition-5 Stage EVAs began when Korzun and Whitson left Pirs at 05:23, August 16. Their exit was delayed for 1 hour 43 minutes due to a valve controlling the flow of gas to the oxygen tank in their Russian Orlan EVA suits being set in the wrong position. Korzun had made the EVA sound simple:

“The first EVA… we will conduct with Peggy, we will take MMOD shield from PMA-1, transfer it with Russian Strela equipment to the Service Module, install this MMOD shield on the corner of the Service Module, and then we will install two antennas which they will use for ham radio; we will install them on the Service Module. And then, we will take old Kromka and install new Kromka. And, we will come back. Approximate time of the EVA will be six hours.”

Once outside, they collected their tools together and prepared the Strela crane attached to the Pirs docking module. The Strela was used to move six micrometeoroid shields from their temporary position on PMA-1 to various positions around the exterior of Zvezda where Korzun and Whitson secured them in place. An additional 17 shields would be carried up to ISS on future Shuttle flights and would be installed on Zvezda on future EVAs. Korzun and Whitson were told not to refurbish the Kromka experiment, which was designed to capture residue from Zvezda’s thrusters. Plans to collect thruster residue by swabbing the exterior of Zvezda were also abandoned as a result of the late start to the EVA. The EVA ended with the astronauts storing their tools and stowing the Strela crane in its parked position. Pirs’ hatch was closed at 09: 48, after an EVA lasting 4 hours 25 minutes.

Preparations for their second EVA occupied most of the next week and Korzun and Treschev left Pirs at 01: 27, August 26. This time the hatch opening was delayed by the search for a pressure leak in one of the airlock hatches. Once again, Korzun described the activities for the NASA website:

“Second EVA. We will use… Docking Compartment—Russian airlock—and we will use Russian spacesuit Orlan. And second EVA we will conduct with Sergei Treschev… We will install, we will replace flow regulator of the thermal control system of the FGB. And we will remove one of the panel of Japanese experiments, and then we will install special equipment for cable outside of the station. EVA time, it’s about six hours.’’

The crew began work by installing a frame on Zarya to act as a temporary stowage area for equipment on future EVAs. They also installed holders on the exterior of Zvezda, to guide EVA astronauts’ umbilicals around the exterior of the

|

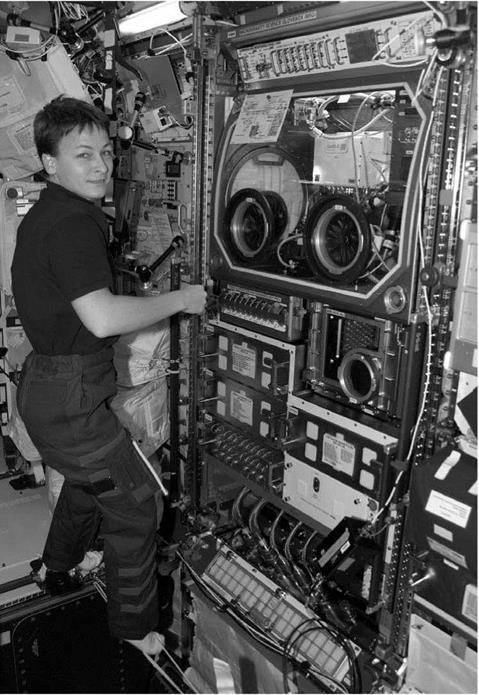

Figure 22. Expedition-5: Peggy Whitson works with the Microgravity Science Glovebox. |

Russian modules. Their next task was to exchange the trays of samples in the Japanese materials exposure experiment on the exterior of Zvezda. Having completed their own tasks the two cosmonauts picked up the tasks left from the shortened first EVA. They replaced the Kromka experiment and confirmed that the deflectors installed to reduce the thruster residue build-up on the exterior of the module were performing their task properly. Finally, they installed two ham radio antennae on the exterior of Zvezda. The EVA ended at 06:48, after 5 hours 21 minutes.

Inside ISS work continued on the experiment programme. Whitson repaired and cleaned the Microgravity Science Glovebox before preparing it for the sixth experiment run. She also down-linked a video tour of Destiny, pointing out a number of the principal experiments. On August 30, she serviced the American EMUs in the Quest Airlock Module. She also partially removed the EXPRESS-2 rack in Destiny to replace a smoke detector. The crew had three days off over the American Labor Day weekend.

On the first day after the holiday, the crew began their planning for the arrival of STS-112. In preparation for the three EVAs associated with that flight they processed the batteries in the EMUs held in the Quest airlock. During the remainder of the week they participated in an emergency procedures exercise and continued the experiments in the Microgravity Science Glovebox. On September 5, Whitson and Korzun took turns to control the SSRMS, including allowing the cameras on the end-effector and the POA to view the snare wires on each other as they were operated. They also grappled and un-grappled the fourth and final PDGF on the MBS, ensuring that it was working correctly. The following day much of the equipment in Destiny was powered down to allow the crew to replace an RPCM. Huntsville began applying power to the module’s equipment as the crew began their sleep period.

Whitson removed the final sample from the SUBSA experiment on September 11, thereby completing the first experiment in the Microgravity Science glovebox. The following day Korzun and Whitson used the SSRMS to view the nadir CBM on Unity. The move was prompted by the discovery of debris on Leonardo’s CBM following the flight of STS-111. Unity’s CBM was inspected with its protective petals open and closed, and the images down-linked to Houston for further investigation of the problem.

On September 13 the crew reached their 100th day in orbit. During the day Whitson set up and activated the ultrasound equipment in the HRF rack in Destiny. She then spent the next four hours using the equipment to capture videos of herself. The ultrasound equipment was designed for use in experiments, but it also had the future capability to be used in diagnosing an illness among the crew. That night Korolev commanded the rockets on Progress M-46 to fire, raising the station’s orbit in preparation for the launch of Progress M1-9.

Sean O’Keefe spoke to the Expedition-5 crew on September 15. He named Peggy Whitson as NASA’s first ISS Science Officer and told the three astronauts that it was time to increase the station’s main mission: science. Whitson and Korzun repaired the CDRA in Destiny the following day, and it was subsequently able to function as planned for the first time since its launch in February 2002. Whitson also prepared the Microgravity Science Glovebox for the first in a run of new experiments called Pore

Formation and Mobility Investigation (PFMI), whereby a transparent material was melted in the glovebox to see how bubbles formed and moved in molten materials. Throughout the week, Korzun and Treschev continued to load rubbish into Progress M-46, in preparation for its undocking. The also began packing items for their own return to Earth on STS-113, scheduled for launch on October 2. Progress M-46 was undocked at 09:58, September 24. The Russians kept the spacecraft in orbit for two weeks, employing its cameras to film smog over northeastern Russia, before de-orbiting it on October 14.