PROGRESS M-46

Progress M-46 was launched from Tyuratam at 13:37, June 26, 2002. While the spacecraft carried out a standard Soyuz rendezvous Korzun and Treschev rehearsed the back-up manual docking procedures using the TORU equipment set up in Zvezda. An automated docking occurred at 02: 23, June 29, and the hatches between the two vehicles were opened at 05: 30. The Expedition-5 crew began the long job of emptying the Progress and logging all of its contents on to the ISS’ computerised monitoring system. They also performed standard maintenance inside Zarya.

The first week of July was one of light duties with lots of free time for the three astronauts. On July 3, Whitson repaired the MCOR and bought it back on-line following a 3-week outage.

In a pre-flight interview Whitson had described the future tasks planned for the MT and the SSRMS:

“So, currently our arm is sitting on the Laboratory module. The shoulder is sitting on the Laboratory module, and we’ll use the arm off the Laboratory, grab the Mobile Base System out of the payload bay, and attach it to the Mobile Transporter. And then once the Shuttle’s gone… one of the things we’ll do is we’ll check out the Mobile Base, make sure it’s working correctly, and then we’re going to do the step-off procedure, which means we’ll grab one of the Payload and Data Grapple Fixtures with the arm and then release [it] from the Laboratory, so our new shoulder becomes on this Mobile Base System. And that allows us the capability of moving the arm along the truss. And that’s important for the next phase, when [STS-112] arrives with the next piece of truss, because from that Mobile Base on the end of the truss of S-0, we will reach down into the payload bay and grab the S-1 Truss and pick it up and attach it to S-0. And then during [STS-113] we’ll do the same from the other side, except because of the configuration … the Shuttle arm will pick it up out of the payload bay and then we’ll grab it from the Shuttle and attach it to the station. So it’s going to be an interesting assembly complex, and the Mobile Base is key in positioning the arm in the appropriate place and it is a platform for the arm from which to work.’’

Whitson walked the SSRMS off Destiny for the first time on July 10, when she commanded the free end of the arm to attach itself to a fixture on the S-0 ITS. Following the walk-off, Korzun and Whitson put the SSRMS through the manoeuvres that would be required to support the installation of the S-1 ITS, during the flight of STS-112. Two days later the SSRMS was moved to a series of alternative PDGFs, in order to ensure the power and data flows required for the installation of the S-1 and P-1 ITS elements were functioning correctly.

On July 15, Korzun and Whitson worked together to replace the Desiccant/ Sorbent Bed Assembly in the Carbon Dioxide Removal Assembly (CDRA), in Destiny. While one bed had been performing normally, the bed being replaced had been malfunctioning since Destiny’s launch, in February 2001. A valve between the desiccant and sorbent sides of the bed was stuck in the open position. The replacement took 4 hours to complete, but when the unit was activated on July 20, the new bed showed a similar leak to the original bed, but at a lower rate.

Two days later, the entire crew performed a medical operations drill, to maintain their training in that vital area of crew performance. On the same day, Whitson worked with engineers on the ground to work out a repair procedure for a spacesuit battery that had failed to discharge prior to being recharged. During the week the crew continued with their science programme, working with the Micro-encapsulation Electrostatic Processing Experiment (MEPE), the ADVASC, and the Microgravity Science Glovebox (MSG). Whitson described the importance of the glove box as follows:

“Well, I think science advances a lot slower than any of us would like it to; but specifically during Expedition 5 we’re getting the Microgravity Sciences Glovebox up… this is a facility payload that is going to allow various different investigators to do materials science inside of a confined environment. In the environment of the Space Station, if we do things that involve toxic materials, we need to have several layers of containment, because obviously we can’t just open the window if we have a little toxic fluid escape. So, the Microgravity Sciences Glovebox provides us a level of containment. It allows us to work inside with the rubber gloves up on our arms, and we can manipulate and set up experiments inside a contained environment. And it would be experiments that we couldn’t possibly do without that additional level of containment… We’ve had other smaller glove – boxes flying, which have flown before either on the Shuttle, in Spacelab, and even one on Mir. So there have been previous ones; this is a kind of a facility-class payload, very large, and I think it’s going to really enhance our capabilities in the materials science world.’’

They also participated in an educational broadcast called “Toys in Space’’, whereby they used a number of simple toys to explain the basic principles of physics involved in spaceflight and present on ISS. The scientific work continued throughout the following week, with the crew working on the Solidification Using A Baffle in Sealed Ampules (UABSA) experiment, which was designed to grow semiconductor crystals in microgravity. Whitson activated the MSG and televised the heating and cooling processes involved in heating a semiconductor to melting point and then allowing it to cool. Whitson also monitored the ADVASC, where soybean plants had started growing. All three astronauts performed PuFF experiments in advance of the EVAs planned for mid-August. There was also the Renal Stone Experiment. Whitson said:

“Our experiment is based on some previous data that we’ve collected on the Shuttle and on the NASA/Mir science program, and there we found that crewmembers are at a greater risk of forming renal or kidney stones… And that’s a big deal in spaceflight because, if you’ve ever known anybody who’s formed a kidney stone, it is excruciatingly painful if that stone begins to move, and in essence it will incapacitate a crewmember, and you would probably have to abort the entire mission. So we are interested in trying to reduce that risk of stone formation. We’ve had crewmembers form stones after flight, and there’s one case where they aborted a Russian mission because of a crewmember who formed a stone during flight… that moved. And so… we’re looking at a countermeasure to try and alleviate some of those effects. We’re using a drug that’s commonly used on the ground to inhibit calcium-containing stones, and based on the results of our previous research we’re going to be using potassium citrate in the crewmembers on a daily basis to see if that actually reduces the risk of forming renal stones, and collecting the same data that we collected… before and see if the risk is actually decreased… Our research shows that there really is a higher risk, and it has to do with the fact that the crewmembers tend to be somewhat more dehydrated, as well as the fact that their bones are demineralizing, so there’s a greater level of calcium and phosphate in the urine, which can form crystals and form the nucleus of the stone that could occur.’’

Meanwhile, they continued their repair and maintenance work, replacing remote power converter modules in the Quest Airlock after they had shown the initial signs of malfunction. On July 22, the crew’s treadmill began making “clanking noises’’ when they ran on it. Investigation revealed that the problem lay in one of the rollers that the belt ran over, where a ball bearing had seized. The crew also worked on the Elektron oxygen-generating system, but failed to improve its performance.

|

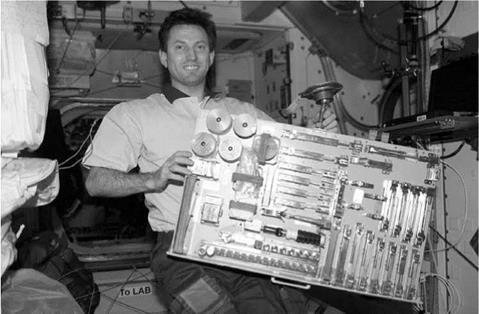

Figure 21. Expedition-5: Sergei Treschev displays one of the station’s many tool kits. MORE CRITICISM |

Following a review of the ISS programme, the director of the US government’s Office of Management and Budget described ISS as one of the Bush government’s “most inefficient and wasteful programmes.” The programme was further described as one of the “biggest [budget] over-runs ever in the federal government.”

The NASA Advisory Council, which had also been tasked to review the ISS programme agreed with the conclusions of the Young Committee. Its report stated that the huge budget over-runs in the ISS programme “cannot be excused and must not be ignored.’’ The Council also agreed that NASA must complete the ISS programme without further budget over-runs for at least two years, during which NASA could not hope to expand the Expedition crew beyond three people. Beyond the criticism, the Advisory Council suggested that NASA begin assigning a modest budget to revive the American Habitation Module and an American CRV.

In March Sean O’Keefe had established a task force to review the station’s ability to support science of merit. On July 10, the force recommended that 15 of the 35 areas of research reviewed be pursued as “first priority’’. The task force also recommended that NASA stop referring to ISS as a “science-driven programme’’, until the size of the Expedition crew was raised to six people. Meanwhile, a Rosaviakosmos spokesman stated that the international agreements on which the ISS programme were based were “deteriorating seriously’’. He suggested that Russia should demand those agreements be renegotiated, and suggested that, if it wished, Russia could build and launch a “European’’ space station as an alternative to ISS.