On April 4, Bursch wrote

“Today is the scheduled launch of STS-110, which will be bringing up the S-0 Truss segment… I am very much looking forward to the arrival of Atlantis and her crew. They promise to bring new care packages from home, fresh ‘smells’ of the Earth and old friends. We know that the work pace will once again speed up, but we are ready! We worked many hours together on the ground developing procedures to use the Space Station robotic arm (SSRMS) as a ‘cherry picker’ as we manoeuvre space walkers ‘flying’ on the end of the arm. This will be the first time that this new arm will be used in such a capacity… Later we heard that the launch was delayed. It is disappointing, but I am fairly familiar with launch delays and understand what the crew is feeling right now. There are many things that need to come together before the SRBs ignite. Some we can control, some we can’t.’’

On the new launch day the countdown proceeded to T — 5 minutes when it was held due to a software difficulty. Atlantis finally climbed away from LC-39B at 16: 44, April 8, 2002, just 12 seconds before the end of the 5-minute launch window. Mission Specialist Jerry Ross was beginning his record-breaking seventh spaceflight. The ISS was high over the Atlantic Ocean and approaching the US eastern seaboard as a live video link with MCC Houston allowed the Expedition-4 crew to watch Atlantis climb into space.

In its payload bay Atlantis carried the first segment of the Integrated Truss Structure (ITS). The $600 million, 13.4m long S-0 (Starboard-0) ITS would be attached to Destiny’s upper surface and would form the centre element of the 100 m long ITS. Later Shuttle flights would deliver a further eight ITS elements, to be located four on either side of the S-0 ITS. The elements on the station’s port (left) side would be numbered P-1, P-3, P-4, P-5, P-6, with P-6 being re-located from its temporary position on top of the Z-1 Truss. Those segments on the starboard (right) side would be numbered S-1, S-3, S-4, S-5, S-6. P-3, and P-4 would be launched as a single combined unit, as would S-3 and S-4. The P-2 and S-2 ITS elements had been part of a larger Space Station Freedom design, but had been deleted when the ISS design was downsized. The remaining ITS elements were not renumbered at that time and there are no P-2 and S-2 ITS in the current ISS design. STS-110 would also deliver the $190 million Mobile Transporter (MT) for the SSRMS. Built in Canada, the MT will allow the SSRSM to travel along rails on the ITS following the delivery of the Mobile Base System onboard a later flight.

Nine minutes after launch Atlantis was in orbit and Bloomfield set up the orbiter’s computers for the rendezvous with ISS. The payload bay doors were opened on schedule allowing the flight to continue. Ochoa described the view of the payload bay through the flight deck’s rear windows, including the S-0 ITS, “It takes up pretty much the whole payload bay. You just look out and you think ‘Wow, it looks beautiful and we can’t wait to get started on operations.’ We’re just raring to go.’’ The crew began their sleep period at 21:44, and began their first full day in space at 05: 44, April 9. Bloomfield’s crew spent the day performing the standard rendezvous routines and preparing their equipment for the docked operations ahead. Onboard ISS, the Expedition-4 crew spent their time preparing for their visitors, having adjusted their sleep period routine to match that of the STS-110 crew. The crew on ISS described Atlantis as a ‘‘hot star on our tail’’. On Atlantis the day ended at 20: 44.

Following a textbook rendezvous Bloomfield and Frick gently docked Atlantis to Destiny’s ram at 12: 05, April 10. On ISS, Bursch rang the ship’s bell that had been installed by the Expedition-1 crew to welcome their first visitors since occupying the station in December. After two hours of post-docking checks the hatches between the two spacecraft were opened at 14: 07. Bursch reported, ‘‘I’m just so happy to see other faces.’’

Following a Safety Briefing from Onufrienko the two crews began a rehearsal of the procedures required for the installation of the S-0 ITS on the upper surface of Destiny. During the procedures, Ochoa and Bursch put the SSRMS through the manoeuvres required to transfer the S-0 from Atlantis’ payload bay to its location on Destiny. Meanwhile, Smith and Walheim transferred the equipment required for their first EVA from Atlantis to the Equipment Fock in Quest. Morin and Ross transferred the Commercial Protein Crystal Growth High Density (CPCG-H) experiment from Atlantis to the station and powered it on. Data received on the ground showed that it had survived the journey into space without damage. The day ended at 20: 44.

Both crews were woken up at 04: 44, April 11, to begin the assembly work that was the highlight of the flight. Ochoa and Bursch used the SSRMS to grapple the 13.5-tonne S-0 ITS at 05: 00. Thirty minutes later S-0 was out of the payload bay. It was then manoeuvred into place above the Fab Cradle Assembly on Destiny and lowered to a semi-rigid fixing just under four hours after the task was begun. Throughout the installation Bloomfield and Frick operated Atlantis’ RMS so that its cameras could provide additional views to Ochoa and Bursch.

In his pre-launch interview on the NASA Human Spaceflight website Bursch had described the S-0 ITS and the tasks involved in mounting it on ISS in the following terms:

‘‘The S-0 is the first segment that comes up that is crossways on the Fab. And so structurally it’s the backbone of the truss that will be installed on the Fab. Second of all, the S-0 will bring up some equipment onboard that will allow the American segment… of the space station to determine its own attitude, and also to determine its rate. Right now we have computers on the American segment that can control the attitude of station, but we get all of our attitude data, meaning how the Space Station is positioned in space and where it’s positioned in space,

|

Figure 15. STS-110 crew (L to R): Steven Smith, Stephen Frick, Rex Walheim, Ellen Ochoa, Jerry Ross, Michael Bloomfield, Lee Morin. |

from the Russian segment. It’ll be the first time that we’ll be able to do that by ourselves on Space Station. It’ll have GPS [Global Positioning System satellite] antennas that will be able to not only determine a state vector, or a position and a velocity and acceleration in space, but also the attitude of Space Station while it’s flying.

Right now there are four space walks scheduled for, in the installation of the S-0 Truss… we’re going to be using the Big Arm [SSRMS], so myself and Ellen Ochoa will be grappling the S-0 Truss in the Space Shuttle payload bay picking it up out of the payload, and it basically takes up just about the entire payload bay of the Shuttle, pick it up, move it over to the port side, and eventually install it on the top of the Lab. And then there’ll be some preliminary mechanical connections that are made just to hold it temporarily on Space Station. [W]e’ll actually have the two space walkers, Steve Smith and Rex Walheim, waiting in the airlock while we do that… and then they go out the hatch. And there’s some struts… to better structurally attach the S-0 Truss to the Laboratory… There’re two in the front and two in the back of the S-0 that go to the Lab, and those have to be attached… we have mechanical connections that need to be made, to fix the S-0 Truss to the

Lab; there’s also umbilicals that need to be connected, and these are for power to some of the equipment that we have on the S-0 Truss, it’s also data to some of the computers that we have in the S-0 Truss, there’s also video channels that will eventually go to the Mobile Transporter and to the Mobile Base System that comes up on a later mission… There’s a time limit in attaching the S-0 Truss, because there’s equipment, once we take it out of the payload bay, we undo a remote umbilical that powers some of this equipment while it’s in the Space Shuttle payload bay; once we take it out of the payload bay then there’s a clock that starts ticking that says we need to get power to this equipment before, or else we have the chance of losing some of the equipment on S-0.’’

Bursch had only hinted at the S-0’s complexity. It carried over 100 electrical and fluid connectors that would allow current and fluids to flow across the length of the completed ITS. It also contained a number of computers among its 475,000 individual parts. Walz described its function with the following words:

“The addition of the S-0 Truss plus the new command and control software that will come up about a month earlier will allow the U. S. to have a full guidance and navigation capability equivalent to what we have on the Russian segment. So we’ll have GPS antennas and also we have the rate gyro assemblies, and so we will have data from both the U. S. and the Russian segment. And it’ll just make the station a more reliable station, because if one source of data for some reason cuts out, we have this equivalent data on the other side. So it’s just a more robust station.’’

Smith and Walheim had been inside Quest, preparing for the first of four EVAs on STS-110. They exited the airlock at 10:38, and Walheim became the first person to ride the SSRMS. Smith made his own way around the exterior of ISS. Smith, who was making his sixth EVA remarked, “Beautiful, beautiful,’’ as he viewed the sight in front of him. “This is incredible, unbelievable! Amazing! Amazing!’’ added Walheim, who was on his first EVA.

They worked together and unfurled two of the four mounting struts on the S-0 ITS and attached them to Destiny, making permanent fixtures. Next, they deployed trays of avionics equipment and connected a series of power, data, and fluid lines between S-0 and Destiny. They also connected an umbilical system between S-0 and the MT. The MT would run along a small rail track mounted on the ram face of the ITS and act as a mobile base for the SSRMS during future assembly tasks. Throughout the multitude of tasks, Ross and Walz directed the EVA from the Shuttle’s aft flight deck. When the tasks took more time than expected the EVA was extended by one hour. Even then, the astronauts’ limited oxygen supply led to a halt being called before they had installed the final two circuit breakers on S-0. The EVA ended with the astronauts’ return to Quest at 18:24, after 7 hours 48 minutes outside. Both crews began their sleep periods at 20: 44.

April 12 began at 04: 44 for Bloomfield’s crew. Onufrienko’s crew woke up 30 minutes later. The day was occupied by a series of transfers between the two spacecraft. Morin and Ross moved an experimental plant growth chamber from

Atlantis to a rack in Destiny. It would replace the malfunctioning protein crystal growth experiment, which was moved into Atlantis for return to Earth. Walheim and Ochoa installed a new freezer in Destiny, to store future crystal samples. Oxygen and nitrogen was transferred from Atlantis to ISS to replenish the supply in Quest’s tanks. The astronauts completed a number of live interviews in the middle of the day. They also watched a live broadcast by NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe, in which he voiced his vision for the future of NASA. In the afternoon the transfer work continued. The Biomass Production System-Photosynthesis Experiment and System Testing Operation (BPS-PESTO) and the Protein Crystal Growth-Enhanced Gaseous Nitrogen Dewar (PCG-EGN) were both transferred from Atlantis to the station. Both crews had two hours free time before beginning their sleep periods at 20:44.

Meanwhile, the powering up of the S-0 ITS systems had begun almost as soon as the first EVA had finished and had continued since that time. The four computers on the ITS were performing as planned, as were the new devices for determining the position of the station relative to Earth. The Global Positioning System antennae and the truss’ thermal control system were all functioning within normal parameters.

April 13 began at 04: 44, with both crews being woken up for another day of EVA. Ross and Morin left Quest at 10: 09. Ross, who was on his seventh flight and was making his eighth EVA had been an astronaut for 20 years and had specialised in EVA, participating in the development of many of the tools that his colleagues would use to construct ISS. As he told a pre-flight interview, “I know what to expect. I can’t wait to do it again… I think it’s a religion. Literally, it’s the human being in the space element as close as you can get. To do it safely and efficiently is a challenge.’’ Ross and Morin were both grandfathers and had therefore earned themselves the nickname the Silver Team for their EVAs. During the EVA, Smith, working inside the station, asked Morin, “how do you like this fraternity so far?’’ Morin replied, “It’s pretty wild.’’ Once the two men had collected their tools Morin rode the work platform in the end-effector of the SSRMS, while Ross made his own way around the exterior of the station. They lowered the second pair of struts supporting the S-0 ITS and connected them permanently to Destiny before removing the panels and clamps that had supported the truss during launch.

The two men also connected a second cable and reel to the MT; the two systems operated independently, offering redundancy in the case of failure. Ross attempted, unsuccessfully, to remove a restraining bolt from the mechanism designed to guillotine the MT umbilical in an emergency. The attempt was abandoned rather than waste precious time. Both men returned to Quest and the EVA ended at 17: 39, after 7 hours 30 minutes. Following the EVA, Frick fired Atlantis’ manoeuvring thrusters in the first of three series of burns to raise the station’s orbit.

During the day, the first readings were made with the PCG-EGN experiment, which had been placed in Zarya. A muffler installed following transfer to the station had to be removed on April 15, when it caused humidity to rise inside the environment chambers of the experiment. The final samples were also recovered from the ADVASC and the experiment was powered off before being transferred to Atlantis for return to Earth. Both crews ended their day at 20: 44.

Smith and Walheim’s third EVA was on April 14; they left Quest at 09:48. Smith rode the SSRMS while Walheim relied on the strength in his arms to move himself around. Their first task was to release the claw-like device that had originally held the S-0 ITS in place above Destiny, before its four legs were lowered and secured in place. Next, they reconfigured a number of electrical and data connections on the SSRMS, to allow it to be commanded through the S-0 ITS. The cables had become stiff in the cold of space and Smith reported, “These cables are again sticking together [as they had on the first EVA]. It’s a little scary taking them apart because they’re fibre optics.’’ They changed and tested the primary series of connectors before changing and testing the back-up system. At one point Smith admired the view of Earth far below him, remarking, “Beautiful place we live.’’

Moving on, they released the clamps securing the MT in its launch position. This cleared the way for the first tests of the system, planned for April 15. Tests of the new SSRMS connections took longer than planned, so activities using the SSRMS to move an EVA handrail from its launch position on the side of the S-0 ITS were cancelled. Smith and Walheim returned to Quest and ended their EVA at 16: 15, after 6 hours 27 minutes. Following the EVA, Frick performed the second series of manoeuvres to raise the station’s orbit. Inside the station the crew began preparing the ZCG experiment for a 15-day run, beginning on April 22. They also moved the Commercial Generic Bio-processing Apparatus (CGBA) from Atlantis to the station. The workday ended at 20: 44.

After waking up at 04: 44, April 15, the crews spent the day transferring equipment from Atlantis to ISS. Meanwhile, controllers in Houston began the first tests of the MT. At 08 : 22, the MT was commanded to move, at less than 2 cm per minute, from its initial position. The small flatbed car was then commanded to travel 5 m along the track, to its first work position. After approximately 30 minutes of travelling a software problem prevented the car automatically latching itself to the ITS at the work site as it should have done to stabilize itself. Controllers sent a series of commands to achieve the latching down. After moving to a second work site, the car again required the commands to latch it to the ITS to be sent manually, as indeed it did after it returned to the first work site. In all, the car had travelled approximately 22 m at rate of 2.5 cm per second. With the exception of the latching software all MT systems functioned as planned. The work day ended at 20: 44.

At a post-EVA press conference at Houston, STS-110 launch package manager Ben Sellari reported, “We did have a very successful activation of the Mobile Transporter… I think what we’re finding out is how the Mobile Transporter works in zero gravity.’’ On the problems encountered with the MT, Sellari stated that he believed that the MT’s wheels had become misaligned with the two magnetic strips that they travelled along, causing the system to shut down.

Walz had described the MT’s first motion in the following terms: “It moved from its launch position to the initial work site… It works on a standard command from the computer and then all of a sudden it started to move, very, very smoothly and, of course, very, very slowly. It got to a position and

started to latch and something went wrong with the automatic software. The

ground was able to move it manually.”

The crew were awake once more at 04:44, April 16. The highlight of the day was the fourth and last EVA, which started at 10:29. Ross and Morin began by pivoting the Airlock Spur away from the S-0 ITS and connected it to Quest, giving future EVA astronauts an easy, direct route between the two. They tested micro-switches on the exterior of the S-0 ITS that would be used to confirm the attachment of later ITS segments and installed two 40-watt halogen lights on the exterior of Unity and Destiny. Next, they erected a work platform on the exterior of the station and installed the two S-0 ITS circuit breakers that had not been installed during EVA-1. Shock absorbers were attached to the MT, to prevent vibrations on the ITS during future EVAs from reaching the SSRMS. During the EVA, Ross joked, “Sure beats the dollar an hour I used to get for baling hay.” Struck by the view of Earth he exclaimed, “This is what I call a room with a view.” During the EVA they observed a thunderstorm over the Pacific Ocean and the Moon over the Atlantic Ocean.

The two men also returned to the bolt that Ross had not been able to disconnect on the MT umbilical guillotine, during the second EVA. They were still unable to remove the bolt, so the problem was left for a later EVA team to resolve. Finally, they tied down an insulation blanket that had come loose around a navigational antenna on the S-0 ITS. Plans to deploy a gas analyser were abandoned when the equipment proved faulty. The EVA ended at 17: 06, after 6 hours 37 minutes. While the EVA went ahead, Onufrienko, Bloomfield, Frick, and Smith continued to transfer equipment in both directions between Atlantis and ISS. The day ended at 20: 14, following the crew’s evening meal.

One of the final joint activities was to transfer the Arctic-1 refrigerator from Atlantis to ISS. It would be used to store samples awaiting return to Earth. With the new item installed and powered on, the Bio-Technology Refrigerator, which had been used for the same function until that point was powered off. Bloomfield led his crew back to Atlantis and sealed the hatches at 12: 04, April 17. Following pressure checks the orbiter was undocked from Destiny at 14: 31, and backed away. Frick flew Atlantis on a 1.25 circuit fly-around of ISS before firing her thrusters at 16: 15, when his spacecraft was directly above ISS, to complete the separation. The crew spent the remainder of the day preparing their spacecraft for the return to Earth.

The last full day of the flight began at 03: 44 April 18. The crew spent it preparing for re-entry. During the end-of-flight press conference they were given the opportunity to sum up their feelings. Bloomfield said, “We made our first step toward our commitment to our International Partners. Once work on the truss and arrays is finished we will actually have enough power that we can add two more laboratories.’’ Those two laboratories would be the European “Columbus” and the Japanese “Kibo” science modules.

Asked about his record-breaking ninth EVA, Ross answered, “I felt the same on this one as I did on the first one, totally enthralled. The spacewalks were incredible.’’

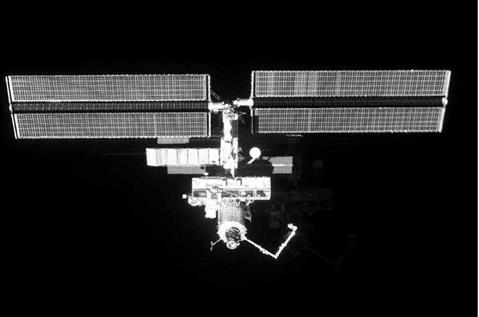

|

Figure 16. As STS-110 leaves the International Space Station, the Starboard-0 Integrated Truss Structure is visible on Destiny’s zenith. |

Smith took a question on his feelings when viewing Earth from space, but knowing that there were numerous wars being fought on the planet’s surface, he answered,

“Every time one of us looks out the window, we have really strong feelings about Earth. It looks very peaceful from up here and it really is very hard to believe that there is strife in different places on Earth. I think we are really good ambassadors, when we come back, about being good to the Earth and promoting peace.’’

Retrofire occurred at 11:20 April 19 and Frick flew Atlantis to a safe landing at KSC at 12: 27. Capcom at Houston told the crew, “That was a great landing and a great way to end a mission that has been superb in all respects.’’

After leaving Atlantis the crew were greeted by the new NASA Administrator, Sean O’Keefe. Bloomfield told the waiting crowd,

“We just got done with an incredible mission up to the International Space Station. We had an outstanding time while we were up there… It’s great to be back home. Please don’t forget those folks that are still up there on the International Space Station. Keep them in your thoughts and prayers.’’

|

SOYUZ TM-34 DELIVERS A FRESH CREW RETURN VEHICLE

|

Even as STS-110 prepared to return to Earth, Onufrienko, Bursch, and Walz were working hard to place ISS into hibernation mode. On April 20, they sealed themselves inside Soyuz TM-33 and undocked from Zarya’s nadir at 05: 02. Onufrienko then flew the spacecraft to a docking with Pirs’ nadir at 05: 35. On returning to ISS they reactivated the systems that they had turned off before the manoeuvre. The change of position had cleared Zarya’s nadir for the arrival of Soyuz TM-34, the new CRV due to replace Soyuz TM-33.

The last Soyuz TM spacecraft, Soyuz TM-34, was launched at 02: 26, April 25, 2002. Flight Commander Yuri Gidzenko was returning to ISS, having served as a member of the Expedition-1 crew. Interviewed before that flight, Gidzenko described the standard 2-day Soyuz flight as follows:

“OK, previously it took only one day from taking off ’til docking between the Soyuz vehicle and the space station. After that, our specialists decided to increase this period of time to two days. It’s maybe more comfortable for crew and more convenient for ground people to calculate our orbit and to calculate inputs so that we can dock. Then for two days, we are going to alter the orbit so that we gradually approach the station. After two days, in Orbit 32, we’ll begin the process of docking. We’ll still have a distant approach, then we approach the station, then we have the docking itself. As a rule this is all done automatically, on an automated mode; the astronauts or cosmonauts are monitoring the process, and if something does occur with the automatic docking, well then the crew gets involved and does it manually. Specifically I have two levers that would allow me to control the vehicle to do the approach and docking manually. Then following the docking we check the seal, equalizing pressure between the transport vehicle and the ISS. We open hatches. Then we start working on the station.’’

Roberto Vittori was a professional Italian astronaut and Mark Shuttleworth, who held joint South African and British citizenship, was the second paying visitor to the station. The launch of Soyuz TM-34 passed without incident and the spacecraft began a standard 2-day rendezvous, docking with Zarya’s nadir at 03: 56, April 26. Hatches between the two spacecraft were opened at 05: 25, and the Soyuz crew floated into Zarya for their safety briefing.

South African President Thabo Mbeki called to congratulate Shuttleworth, who he called “the first African citizen in space’’. The President told him, “The whole

|

Figure 17. Expedition-14: The Expedition-4 and Soyuz TM-34 crews pose in Zvezda. (rear row) Carl Walz, Yuri Onufrienko, Daniel Bursch. (front row) Roberto Vittori, Yuri Gidzenko, and South African Spaceflight Participant Mark Shuttleworth. |

continent is proud that at last we have one of our own people from Africa up in space… It’s a proud Freedom Day because of what you’ve done."

In reply, Shuttleworth described his launch in the following terms, “I had moments of terror, moments of sheer upliftment and exhilaration.’’ He also described ISS, “It’s amazingly roomy… Although it’s very, very large, we have to move very carefully. As you can see around us, there are tons of very precious and very sophisticated equipment. We hope that we will be good guests.’’ Of his home planet, Shuttleworth said, “I have truly never seen anything as beautiful as the Earth from space. I can’t imagine anything that could surpass that.’’

Following the farce and ill-will surrounding Denis Tito’s flight on Soyuz TM-32, NASA and RCS Energia had negotiated a set of rules governing the inclusion of Space Flight Participants (commercial passengers or “space tourists’’) in the otherwise empty third seat on Soyuz “taxi’’ flights to replace the Soyuz CRV attached to ISS. Although Shuttleworth would remain the responsibility of Gidzenko and Onufrienko whilst on the station, he was not required to be escorted while in the American ISS modules, as Tito had been. Shuttleworth had also negotiated the use of a NASA laptop computer to send e-mails from the station and some time on the NASA communications link to download audio and images. Like Tito, Shuttleworth had spent one year training in Korolev, and had even received 1-week training in Houston, which NASA had denied to Tito. Unlike his predecessor, Shuttleworth planned to perform experiments whilst on the station. When interviewed by CNN, Tito remarked that he was pleased that negotiations had formalised the position of Space Flight Participants and had allowed Shuttleworth to fly without the acrimony that had surrounded his own flight the previous year.

In orbit, Shuttleworth spent his time performing experiments in crystal growth, stem cell research, and AIDS research. He also spent long periods looking out of the windows at the magnificent view of Earth. During his stay on ISS he became a national hero in South Africa and also received considerable press coverage in Britain. He spoke with Nelson Mandela during a press conference and was embarrassed when a 14-year-old South African schoolgirl asked him to marry her. The short-duration flight came to an end on May 6, when Gidzenko, Vittori, and Shuttleworth sealed themselves inside Soyuz TM-33 and undocked from Pirs at 20: 31. They landed in Kazakhstan at 23:51. Shuttleworth described his flight as “the most extraordinary experience”.

In 2003, it was announced that female Russian cosmonaut Nadezhda Kutelnaya had been named to the Soyuz TM-34 crew, but had been removed to make way for Shuttleworth who had paid $20 million for his flight. It turned out that Kutelnaya had previously been named in the original crew for Soyuz TM-32, but had also been removed on that occasion, to make way for the fee-paying Denis Tito.

Even as the Soyuz TM-33/Soyuz TM-34 exchange took place in orbit, RCS Energia remained in serious financial difficulty. The failure of the Russian government to pay the company millions of roubles that it was owed meant that Energia was unable to purchase the equipment required to finish manufacturing a number of Progress spacecraft then under construction. The funding problem particularly threatened the Progress vehicle due for launch in January 2003. Energia officials admitted that contingency plans were in place, in full co-operation with NASA, to end permanent occupation of ISS if the problems with funding persisted. The station would then be occupied by visiting crews on self-sufficient, short-duration Shuttle flights, as Skylab and the early Soviet Salyut stations had been. At the same time work on the Soyuz TMA-1 spacecraft, due to replace Soyuz TM-34 in October 2002, and others of its class, was also running behind schedule. If the new spacecraft were not available in time then permanent occupancy of ISS would have to be temporarily suspended.

While demanding that the Russians meet their contractual agreements the Americans continued to move on with their own decision to stop developing ISS after it reached “Core Complete”. Few people now believed that they would ever see ISS reach the original “Assembly Complete” configuration. The on-going Russian budgetary difficulties only served to highlight the far-reaching implications of the American decision to cancel the development of the X-38 CRV and the failure to develop relatively inexpensive robotic cargo delivery vehicles. The combination of a new American President (George W. Bush) and a new Administrator (O’Keefe) at NASA, both of whom had vowed to rein in spending on ISS, meant that on this occasion NASA was far less likely to hurry to the Russians’ aid with an injection of much needed cash. The time had come for the Russian government to prove that they intended to live up to their contractual agreements and support ISS, or admit that they can no longer afford to do so due to pressing problems at home on Earth and withdraw from the programme. The latter would no doubt have seen the end of the Russian space programme for the foreseeable future and would have been a very sad day indeed.

In the wake of Shuttleworth’s successful flight, Energia announced that it was likely that Space Flight Participants would be included in most Soyuz taxi flight crews. The private flights, which cost $20 million each, including a very basic training regime in Korolev, were contracted through the American company Space Adventures. They were a major source of income for the Russians, allowing them to plough the money back into the Soyuz/Progress spacecraft needed to fulfil their contractual commitments to ISS. Lance Bass, a rock band vocalist, was originally in line for the space participant’s couch on the October 2002 Soyuz taxi flight, but failed to raise the $20 million to pay for his flight. The Russians removed him from the flight roster.

At the same time, NASA Administrator Sean O’Keefe announced that NASA would select an Educator Astronaut, a teacher, in each subsequent group of new astronauts selected after 2003. Unlike Christa McAuliffe, who was a passenger on STS-51L, the Educator Astronauts would be professional astronauts, serving as Mission Specialists, with the years of training that that would involve before they made their first flight into orbit. The first Educator Astronaut to be selected was Barbara Morgan, Christa McAuliffe’s back-up in 1986. The Educator Astronauts would be used to encourage students to study mathematics, engineering, and spaceflight-related science subjects.

Following the departure of Soyuz TM-34 Onufrienko and the Expedition-4 crew had 1.5 days of free time before splitting their time between long-running experiments and preparing to come home. During the second week of May, Onufrienko repaired the Elektron oxygen generator, which had been malfunctioning again and had been off-line. From Korolev, Valeri Lyndin assured the media, “There is enough oxygen in the station, so there is nothing terrible about this. There is enough oxygen to last three or more months.’’ He continued, “Elektron was working on the ISS, taking oxygen from water, but there are other mechanisms, and they are getting oxygen with the help of these systems now… The system is automated, so you can command it from Earth or from the computers onboard. We are taking the appropriate measures.’’ In the last days of their stay, Onufrienko’s crew performed their final experiments.

STS-111 DELIVERS EXPEDITION-5 AND REPAIRS THE SSRMS

|

STS-111 |

|

|

COMMANDER |

Kenneth Cockrell |

|

PILOT |

Paul Lockhart |

|

MISSION SPECIALISTS |

Franklin Chang-Diaz, Phillippe Perrin (France) |

|

EXPEDITION-5 (up) |

Valeri Korzun (Russia), Sergei Treschev (Russia), Peggy Whitson |

|

EXPEDITION-4 (down) |

Yuri Onufrienko (Russia), Daniel Bursch, Carl Walz |

STS-111 would take the Expedition-5 crew, Valeri Korzun, Sergei Treschev, and Peggy Whitson, up to ISS and return the Expedition-4 crew, Yuri Onufrienko, Daniel Bursch, Carl Walz, to Earth. It also carried the MPLM Leonardo, with experiment racks and three stowage and re-supply racks for Destiny. The flight would deliver the Mobile Base System (MBS) which, when mounted on the MT, would complete the Canadian Mobile Servicing System (MSS). When the assembly of the MBS was complete the SSRMS would be moved end over end, from its position on the exterior of Destiny, to mount itself on the MBS. Once in place, the MBS would be able to run along rails on the ram face of the ITS. This combination offered new mobility that would be used extensively in the remainder of the ISS construction programme, as well as in support of numerous EVAs and experiments. There would be three EVAs during the flight of STS-111, two in support of the MBS, and one to replace a faulty wrist joint on the SSRMS. The latter repair had resulted in a 1-month launch delay, while the crew learnt the new repair procedures.

The flight was due to be launched at 19:22, May 30, 2002, but on May 28 a problem was found in one of Endeavour’s Auxiliary Power Units (APUs). It was repaired on the launch pad, without delaying the launch. On May 30, the launch attempt was cancelled at 19 : 21, due to the fact that there were thunderstorms within the area around the Kennedy Space Centre.

The launch was rescheduled for 24 hours later, with the countdown resuming at T — 11 hours and propellant loading commencing at 10: 00. However, at the Tanking Meeting, prior to commencing propellant loading, mission managers decided that there was little chance of the weather improving in time for the day’s launch. This time the launch was re-set for June 4, and the Rotating Service Structure was moved back around the Shuttle on the launch pad, to protect it from the weather. On June 2, the launch was moved back a further 24 hours, to June 5, due to work on a malfunctioning gaseous nitrogen pressure regulator in Endeavour’s left-hand Orbital Attitude and Manoeuvring System (OAMS) pod. The regulator had malfunctioned earlier in the countdown and the decision had been taken to change it.

As the new countdown reached its final stages, Launch Director Mike Leinbach told Cockrell, “Sorry we had to keep you here an extra 6 days. Good luck, have a good flight.’’ Cockrell replied, “We’ll do a good job for you.’’

STS-111 finally lifted off at 17: 23, June 5, 2002, while ISS was west of Perth, Australia. At launch Frank Culbertson, who had been Commander of the Expedition-3 crew, and who was working the Capcom’s position in Houston, informed the Expedition-4 crew, “It’s on the way. I know you will be happy to hear that.’’ After 182 days in space Bursch yelled, “All right!’’ Walz was more reserved saying, “Good. We look forward to seeing you.’’

Following a perfect launch, Endeavour entered the correct orbit and was configured for orbital flight. As Endeavour left Earth, Chang-Diaz equalled Jerry Ross’ record set on STS-110, becoming the second person to fly in space seven times. Asked about his new record in a pre-flight interview he had replied, “I’m hoping that these kinds of records will be easily broken and many times over. And I’m hoping that there will be many, many people who will fly not 7 or 8 times, but 10, 15 times.’’ The crew’s day ended just 3 hours after launch when they settled down to their first night in space.

June 6 was spent doing all of the routine things that a Shuttle crew does during their first full day in space. While Cockrell and Lockhart concentrated on the rendezvous, Perrin and Chang-Diaz fitted the centreline camera and deployed the docking ring. They also checked out the EMUs that they would wear during their three EVAs. On ISS, Onufrienko, Walz, and Bursch prepared the station for the arrival of the Expedition-5 crew and the visitors that would deliver them.

Day 3, June 7, began at 05: 30. Endeavour followed a standard rendezvous path. During the final approach Dan Bursch had remarked, “It’s a great day, a great day.’’ He then rang the Station’s bell to mark Endeavour’s arrival. Soft-docking, on Destiny’s ram, occurred at 12:25. After waiting 1 hour for oscillations to damp down, hard-docking took place at 13: 27. Following pressure checks the hatches between the two spacecraft were opened at 14: 08, and the Shuttle and Expedition-5 crews entered Destiny, where the Expedition-4 crew greeted them. One of the Expedition-4 crew noted that the Expedition-5 crew consisted of older individuals and told Cockrell, “We are so glad that you brought our fathers to the International Space Station.’’ Turning to the newcomers he added, “We wish you good luck. Have a good time.’’

Before launch Korzun had described his views on the Expedition crew hand-over:

“What is [the] purpose of the hand-over? We have [a] special book; we will use this book and there is each system described in this book, and there are some empty space[s] which we need to use to write changes between [the] condition of systems which we study on the ground and [the] real condition of this system onboard Station. And maybe… we will study real situation with stowage of the equipment in station… [W]e need to have some times to adapt, maybe first time, I can [watch] Yuri’s activity or Peggy will see Carl’s activity or, Sergei will follow Dan’s example… [N]ow we needn’t use a lot of time for hand-over because each Shuttle crew bring down some video and, we have [the] opportunity to watch video that crew made in space [to] show us [the] situation. And sometimes I think this is a good idea… to watch video and to recognize [the] configuration inside of the module. [It is] very important for us to use INV—this is Inventory Management System.’’

Following a safety brief, the ten astronauts began transferring equipment and experimental results between the two spacecraft. The Expedition-4 crew removed their couch liners from Soyuz TM-34 and stored them in Endeavour, while the Expedition-5 crew installed their own couch liners in the Soyuz and then checked their Russian Sokol pressure suits. Perrin and Chang-Diaz checked the communication link between their EVA suits and the Quest Airlock. With the latter task completed, they officially took up residence on ISS at 18: 55. At the same time Onufrienko, Bursch, and Walz completed their 182-day stay on ISS and became part

|

Figure 18. STS-111 crew (L to R): Phillippe Perrin, Paul Lockhart, Ken Cockrell, Franklin Chang-Diaz. These four were joined by the Expedition-5 crew during launch and the Expedition-4 crew during recovery. |

|

Figure 19. STS-111: Endeavour delivers the Multi-Purpose Logistics Module Leonardo to the International Space Station. |

of Endeavour’s crew. The day ended with the failure of the Flash Evaporator System Primary controller. It was one of three such controllers and had no effect on the station’s operations. An investigation was begun in Houston.

On June 8, the two Expedition crews continued their hand-over. Onboard Endeavour, Cockrell used the RMS to un-berth Leonardo from the payload bay and dock it to Unity’s nadir, at 10:28. Following pressure checks the hatches between Leonardo and Unity were opened at 17:30. All ten astronauts entered the MPLM and began unloading the logistics and equipment that the Expedition-5 crew would use during their stay on ISS. Early in the day the crew reported, “We’re hearing a pretty loud audible noise, kind of a growling noise.’’ At the same time, one of the station’s four CMGs mounted in the Z-1 Truss seized. It was commanded to spin down (lose speed) and was then shut down. An investigation began, but the remaining three CMGs and a number of alternative systems for controlling the ISS’s attitude meant that the failure had no immediate effect on the mission. Flight director Paul Hill told a press conference, “Big picture wise, losing a CMG is a big deal. From a risk perspective right now, we’re in good shape. But this is a major component that’s failed and we’re going to do the best we can to get the next CMG ready to fly.’’ There was a spare CMG in storage in America, but the full Shuttle manifest meant that it could not be launched before 2003.

As the day continued Perrin and Chang-Diaz checked out their EMUs, as well as the tools and procedures for their first EVA, which would take place the following day. During a briefing from the ground the astronauts were updated on the attempt by Lance Bass to purchase a Space Flight Participant’s position on the up-coming October Soyuz taxi flight to ISS. Expedition-5 crew Commander Valeri Korzun replied, “We would be happy to see one of the Supermodels.’’ He added, “But this is a joke and we will be very happy to receive any space tourist. They’re very welcome here… Probably someone with certain professional qualities would be better. But it would not make any difference to our greetings.’’ That was still a very Russian point of view. On the subject of his own flight Korzun was equally positive saying, “Physically and psychologically, we are prepared to fly at least a year and a half.’’

Regarding the CMG failure, during the day Flight Director Rick LaBrode explained:

“All indications at this point do appear to be a mechanical failure. We saw increases in vibration. We saw increases in bearing temperatures, increased currents and decrease in speed. It looks obviously like a bearing seized.’’

Perrin and Chang-Diaz left the Quest airlock at 11: 27, June 9, at the beginning of a 7-hour 14-minute EVA. Lockhart choreographed the EVA from Endeavour’s aft flight deck, while Korzun and Whitson operated the SSRMS. Throughout the EVA Cockrell used the cameras mounted on Endeavour’s RMS to view the astronauts’ activities. Korzun described the EVA tasks in his pre-launch interview:

“[Everybody on our crew has personal tasks during this activity. I will support [the] EVA crewmember on the Shuttle who is [riding the] robot arm during EVA 1, and Peggy will grapple [the] MBS and translate [the] MBS and connect [the] MBS to the MT, and… Sergei will check [the] station systems during this activity and help us with [a] video view during MBS installation… I need to transfer Franklin from [the] Airlock to [the] cargo bay of the Shuttle; he will ungrapple [a] spare PDGF and then I will translate him to the P-6 … He will install this PDGF and then move back to the cargo bay, and unfasten pack of MMOD shield—this is special protection for the Service Module [Zvezda]. And then I will transfer him, with MMOD shield, to the PMA-1. They will, Franklin and Philippe will temporary stowage of this MMOD shield, and [then], during our EVA, we will take this MMOD shield and we will transfer it to the Service Module, and we will install this MMOD shield around the corner of Service Module. They will protect Service Module from meteors during flight.”

The first task was to install a PDGA on the P-6 ITS. The PDGA would be used to move the P-6 from its position on the Z-1 Truss to its final location, on the end of the Port ITS, during the flight of STS-119. That move would be one of the final actions in the construction of the ISS “Core Complete” configuration. Chang-Diaz mounted a foot restraint in the end of the SSRMS and climbed on to it. He collected six thermal shields from their storage place within Endeavour’s payload bay and was then moved alongside PMA-1, between Unity and Zarya. Perrin made his own way to the same location and helped Chang-Diaz to attach the thermal shields temporarily to PMA-1. In an EVA planned for July, Korzun and Whitson would install the shields in their final location, on the exterior of Zvezda, where they would provide additional micrometeoroid protection, bringing the module up to American standards in that capacity.

Admiring the view from their unique location, Chang-Diaz exclaimed, “This is an amazing experience, I tell you.’’

Frenchman Perrin agreed, “Unbelievable.”

Chang Diaz then conducted a visual and photographic inspection of the failed CMG in the Z-1 Truss, a task added to the EVA only a few days earlier. Their final tasks called for the removal of the thermal blankets covering the Mobile Base System (MBS). With the blankets removed Cockrell released the latches that held the MBS securely in Endeavour’s payload bay. Whitson and Walz then grabbed the MBS with the SSRMS and lifted it to a position 1 metre above the MT, on the S-0 ITS. The SSRMS was then powered off, leaving the MBS to become thermally conditioned. Perrin and Chang-Diaz returned to the airlock and the EVA ended at 18:41.

Onufrienko had intended to carry out a short official hand-over ceremony during the day, but a smoke alarm in one of the Russian modules caused that ceremony to be abandoned. After inspecting the relevant module Onufrienko reported, “Everything is OK. Everything is under control. It was a false alarm. Too much dust; that is probably what triggered it.’’

At 09:30, June 10, Whitson and Walz used the SSRMS to transfer the MBS up to the MT. Controllers in Houston then ordered the latches to close, securing the MBS in place. In the future the SSRMS would be walked end over end until it could attach itself to the MBS. In that position it would be possible to ride the MT up and down the track mounted on the ITS. In that way the SSRMS would be able to assist in attaching future ITS elements to the truss. During the afternoon, Onufrienko’s crew held a ceremony to pass command of ISS to Korzun’s crew. Following the hand-over ceremony, Endeavour’s thrusters were used to raise the station’s orbit.

Chang-Diaz and Perrin commenced their second EVA at 11:20, June 11. Lockhart acted as Intravehicular Officer, guiding them through the items in the flight plan. Their first task was to connect a dozen primary and back-up power, data, and video cables to the MBS and the primary power cable between the MBS and the MT. With the latter task completed Houston sent commands to the MT to plug its umbilicals into the S-0 ITS. The two EVA astronauts then connected the Payload Orbital Replacement Unit Accommodation (POA) on the MBS. This was a copy of the end-effector on either end of the SSRMS and would be used in the future to hold cargo while the MT traversed the ITS. Next, they secured four bolts between the MBS and the MT, thereby completing the installation of the MBS. The penultimate task was to move a TV camera to its final position on the MBS, where it would be used to view future assembly work. Finally, the two men added an electrical extension cable to the MBS and photographed all of the connections that they had made. The EVA had been planned to last 6.5 hours but ended at 16: 20, after only 5 hours. In Houston, Canadian astronaut Bob Thirsk told them, “We consider it a wrap. Your professionalism and skill really showed through.’’

Inside ISS, work continued on the Expedition crew hand-over and the transfer of supplies. With Leonardo already unloaded the crews spent much of the day loading equipment and results from the Expedition-4 crew’s experiments into the MPLM for return to Earth. At 22: 19, Walz and Bursch set a new American endurance record, exceeding Shannon Lucid’s 188 consecutive days spent in space.

At 02: 55, June 12, Walz also surpassed Lucid’s overall record of 223 days in space accrued over numerous flights. The day was spent loading Leonardo and continuing the hand-over of the Expedition crews. Chang-Diaz and Perrin also went over plans for their third EVA, planned for the following day. During the afternoon Endeavour performed a second re-boost manoeuvre. The astronauts also downlinked their pictures of forest fires burning in Colorado.

Chang-Diaz and Perrin left the Quest airlock for the third time at 11: 16, June 13. Lockhart controlled the EVA while Cockrell operated Endeavour’s RMS, to allow its cameras to return pictures of the astronauts’ activities. Their task for the day was to change out the primary wrist roll joint in the SSRMS, which had malfunctioned in March 2002. Since that time all SSRMS functions had been performed using the back-up wrist mechanism. Bill Gerstenmaier, Space Station programme deputy manager had described the SSRMS at a STS-111 launch day press conference, saying, “Without the arm, we could not continue to build the station. So the arm needs to be there, and needs to be functioning.’’

The repair began with the removal of the Latch End Effector (LEE) which was secured to an EVA handrail on the exterior of Destiny. This exposed the wrist joint that required replacement. The two astronauts disconnected six bolts holding the wrist roll joint in place and a seventh bolt holding power, data, and video umbilicals, before Perrin removed the joint and carried it down to its stowage position in Endeavour’s payload bay. He then released the six bolts holding the new joint in place in the payload bay and carried it back up to where Chang-Diaz was waiting. Having positioned the joint the two men tightened the six securing bolts and the umbilical bolt, before recovering and replacing the LEE. While Chang-Diaz and Perrin moved the old joint to its final position for its return to Earth, power was applied to the SSRMS so that Bursch and Korzun could run it through as series of test manoeuvres. The SSRMS was returned to full operation at 16:43. Having collected and stored their tools the two astronauts returned to Quest, and the EVA ended at 18: 33, after 7 hours 17 minutes. Throughout the EVA Whitson and Treschev had continued to transfer items from ISS to Endeavour and Leonardo. In the evening an unsuccessful attempt was made to apply electrical power from the MBS to the SSRMS. Initial investigation suggested that a software glitch had prevented the commands travelling between the two units.

The highlight of June 14 was the closing and removal of Leonardo from Unity’s nadir. Just after 12:00 Perrin used Endeavour’s RMS to manoeuvre the MPLM back into the Shuttle’s payload bay, where it was secured at 16: 11. Cockrell then performed a third re-boost manoeuvre using Endeavour’s thrusters. Back on ISS all ten astronauts brought their group activities to a close.

June 15 began with final farewells and the withdrawal of the STS-111 crew to Endeavour before the sealing of the hatches between the two vehicles at 08: 23. Following pressure checks, Endeavour undocked at 10: 32, and moved clear of Destiny’s ram under Lockhart’s control. Onboard ISS, Whitson rang the ship’s bell and announced, “Expedition-4 departing, Endeavour departing.’’ This Naval tradition, initiated by Shepherd, commander of the Expedition-1 crew, had become standard practice on the station whenever spacecraft arrived or departed. Onufrienko, Walz, and Bursch had spent 181 days on the station. Once clear of ISS, Endeavour made 1.25 circuits of the station while the crew exposed video and photographs. Finally, Lockhart manoeuvred the Shuttle away from the station and the crew enjoyed some free time. On ISS, the Expedition-5 crew began their sleep period at 16: 00, adjusting their daily routine to begin at 02: 00, June 26. When they awoke they began the task of unpacking and stowing the items Endeavour had brought to the station.

Preparations for re-entry filled the whole of June 16. Plans to return to Earth were cancelled on both June 17 and 18, when controllers in Houston instructed the Shuttle’s crew to back out of preparation for re-entry due to rain and thunderstorms in the region of the Kennedy Space Centre. In the meantime, Edwards Air Force Base, in California, was activated as a back-up landing site. Following a third wave – off to Florida, Endeavour finally returned to Edwards, landing on the dry lakebed at 13: 58. The Shuttle flight had lasted 7 days 2 hours 26 minutes. Onufrienko, Walz, and Bursch had completed 196 days in space. In the weeks that followed they underwent the full range of medical and re-acclimatisation studies that previous long-duration space station crews had undergone before them. They were all found to be in good health.