EJECTION SEATS AND A FAULTY HATCH

Prior to the first manned Gemini mission, plans were accelerated for the suborbital flight of Gemini 2, which was to test the spacecraft’s heat shield and splash into the South Atlantic carrying two instrument boxes substituting for astronauts. Unlike the GLV-1 mission, this one was jinxed. In addition to a succession delays for technical reasons, it fell prey to severe weather patterns over the Cape. On 20 August 1964 a violent electric storm hit the area and a bolt of lightning struck the Titan II, which had been erected in its gantry the previous month. Many of the delicate instruments were damaged, and the vehicle had to be dismantled in order to check thousands of vital components and revalidate its systems. A second launch attempt was aborted when the rocket had to be removed from the pad again to protect it from the fierce winds of the rapidly developing Hurricane Cleo. Soon after the rocket had returned to the pad, the prospect of a battering by Hurricane Dora caused it to be removed a third time on 11 September. And then on 9 December the Titan II suffered a launch pad shutdown due to a malfunction in the booster’s hydraulic system. The mission was rescheduled for 19 January 1965. This time the launch was successful, and the spacecraft splashed down 25 miles from the recovery force. The spacecraft and heat shield were found to have performed as required, and NASA gave the go-ahead for the first manned launch.

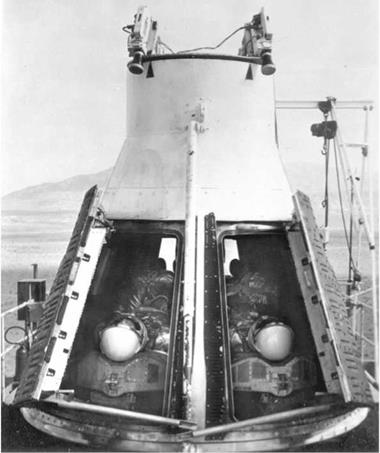

Unlike the cramped Mercury, the Gemini spacecraft was fitted with powerful ejection seats that either astronaut could activate to escape a launch pad explosion. The seats ejected with such a tremendous thrust that the astronauts hoped never to find themselves in situation where they would have to eject. Tests were carried out using mannequins, and one of the final tests occurred on 16 January with Grissom and Young looking on as ground controllers sent the firing signal to the spacecraft. In milliseconds, powerful solid rocket motors hurled the dummy astronauts along with their seats and parachutes through the simultaneously opened hatch exits. At least, that was the plan. Both Grissom and Young winced visibly when one of the hatches failed to open and the seated mannequin was propelled straight through it. “That would give you one hell of a headache,” the laconic Young later observed, “but a short one.”

|

In the event of a launch pad explosion, the Gemini spacecraft was equipped with ejection seats to blast the astronauts 800 feet from the pad. To test the ejection and parachute systems, boilerplate capsules were mounted in launch attitude on top of a high tower and the seats carrying mannequin astronauts were fired across the desert. (Photo: NASA) |

The test served only to reinforce in the astronauts their mistrust of the system, and gave Grissom another reason to dislike the word “hatch.” Although a further test two weeks later worked perfectly, somewhat restoring their faith in the escape apparatus, they still hoped they would never have to use it.