THE FIRST GEMINI CREW

The following month the new program had been given a name. On 3 January 1962 NASA announced the two-man spacecraft would be called Gemini, the Latin word for “twins.” This followed a suggestion by Alex P. Nagy from NASA’s Office of Manned Space Flight at the agency’s Washington Headquarters, who not only had the distinction of naming the nation’s new space program but also of receiving the associated prize of a bottle of scotch whiskey. Appropriately enough, Gemini was the name given to the third constellation of the zodiac (the sign in astrology that is controlled by Mercury) and comprised of two stars called Castor and Pollux. The Gemini spacecraft

|

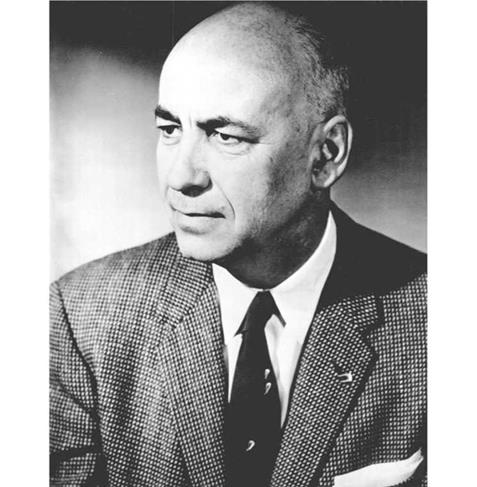

Dr. Robert Gilruth of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston. (Photo: NASA) |

|

|

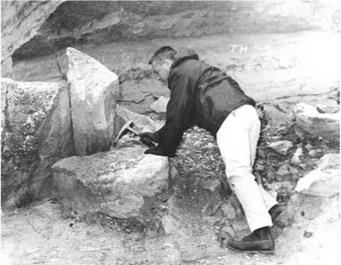

In preparation for future Apollo lunar missions, all eligible astronauts including Gus Grissom underwent geology training, and he is shown here in the Grand Canyon in 1964. (Photo: NASA)

|

|

Part of the fun of astronaut geology training in the Grand Canyon was riding out on mules. (Photo: NASA)

was the same high-drag shape as the Mercury capsule, but with around 50 percent greater interior room.

The first test flight (GLV-1) of a Gemini spacecraft atop a Titan II took place on 8 April 1964, using Launch Complex 19 at Cape Canaveral, and it was a complete success. The second stage of the Titan II and the attached, uninhabited spacecraft orbited the Earth 64 times, although the official part of the mission ended after only three orbits. As there were no plans to retrieve the spacecraft, the entire assembly of the spacecraft and the upper stage of the booster reentered the atmosphere four days later and burned up over the South Atlantic. All the major mission objectives had been met, principally that of testing the structural integrity of the spacecraft and the modified Titan II booster and proving that the spacecraft was capable of carrying a crew.

|

Liftoff of the first Gemini-Titan II flight (GLV-1) on 8 April 1964. (Photo: NASA) |

As history records, Alan Shepard was actually the original choice to command the first Gemini orbital test flight with co-pilot Tom Stafford, but to his consternation he fell victim to a debilitating inner ear ailment (later diagnosed as Meniere’s disease) which caused him to be medically disqualified from flying in October 1963.

Early in 1964 Missiles and Rockets magazine made a surprise claim. “There are unconfirmed reports that the first Gemini astronaut team will be made up of Virgil (‘Gus’) Grissom and Neal [sic] Armstrong. Grissom is the member of the original Mercury astronaut team who has worked most closely with McDonnell Aircraft Corp. in design and development of the spacecraft. Armstrong has chalked up many flight hours during the X-15 program. Official announcement of the first pilot team is expected around May 1.”2

Grissom had been penciled in to command the fourth manned Gemini flight and the grounding of Shepard caused Deke Slayton (who had himself been grounded before he could make a Mercury flight and, as the newly named deputy director of Flight Crew Operations, was in charge of crew assignments) to promote Gus to the first manned mission, the three-orbit test flight designated Gemini 3. Now a suitable copilot was needed to partner him, and Slayton wanted to give flight experience to the nine newly selected astronauts. He subsequently paired them in the first Gemini flights with an experienced astronaut from the Mercury program.

At first the Gemini 3 mission was scheduled for launch in December 1964. Air Force Capt. Frank Borman had recently finished his astronaut training and, like the other eight pilots of the second astronaut group, was wondering when he might be assigned to a Gemini mission and which one it would be. Everyone knew that the Mercury astronauts who would fly as mission commanders on Gemini would have the power to veto any decision that Slayton might make regarding their co-pilot in order to avoid any potential clashes of personality.

It came as an unexpected but welcome surprise when Borman received a phone call one day from Grissom, who told him (although it was yet to be made official) that he, Grissom, had been named by Slayton to command the first manned Gemini mission and Borman had been tentatively assigned as his co-pilot. Grissom wanted to talk over the mission and its requirements before the final crewing decision was made. The two men arranged to meet at his house, and Borman could not get there soon enough. They spent an hour or so deep in conversation and not long after that Borman was informed of a change of crewing that meant Grissom would fly with another member of the Group 2 astronauts.

“I haven’t the slightest idea what went wrong,” Borman later pointed out in his autobiography, “but he apparently wasn’t too impressed with me. The next thing I knew, I had been replaced by John Young, who didn’t try very hard to conceal his delight, for which I couldn’t blame him.”3

To soften Borman’s disappointment at the news, Slayton told him that he would instead be assigned as backup commander of the second mission, with co-pilot Jim Lovell.

|

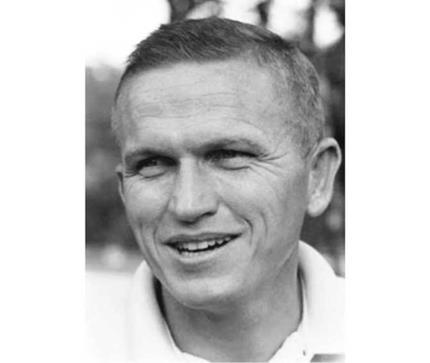

USAF Capt. Frank Borman, Group 2 astronaut. (Photo: NASA) |