A CHANGE OF PROCEDURES

Despite the loss of Liberty Bell 7, the MR-4 mission was considered to have been a success. Eventually, rather than delay the Mercury program, a fully mechanical hatch was designed to replace the explosive version, but it was deemed to be cumbersome to operate and far too heavy, exceeding set weight constraints. The explosive hatch would remain. What did change was the implementation of a new set of splashdown procedures. These required the astronaut to leave the removable firing safety pin in place until after the helicopter’s recovery cable had been hooked up.

The Mercury program ended after four more flights – all orbital missions – with none of the astronauts opting to blow the hatch at sea and travel to the waiting carrier aboard the recovery helicopter. John Glenn (Friendship 7), Wally Schirra (Sigma 7) and Gordon Cooper (Faith 7) all elected to remain in their capsule until it had been safely secured onboard ship, following which they would blow the hatch. The only exception was Scott Carpenter, whose MA-7 overshot the planned landing zone by 250 nautical miles, which meant it would be a considerable time before he and his spacecraft could be retrieved from the sea. Rather than remain in the unstable craft with the near-certainty of becoming seasick, or blow the side hatch and risk having Aurora 7 fill with seawater and sink, he squeezed up and out through the alternative recovery compartment exit at the top of the spacecraft.

The fact that his spacecraft had been lost at sea remained a source of irritation and torment for Gus Grissom.

“We had worked so hard and had overcome so much to get Liberty Bell launched that it just seemed tragic that a glitch robbed us of the capsule and its instruments at the very last minute. It was especially hard for me, as a professional pilot. In all my years of flying – including combat in Korea – this was the first time that my aircraft and I had not come back together. In my entire career as a pilot, Liberty Bell was the first thing I had ever lost. We tried for weeks afterwards to find out what happened, and how it happened. I even crawled into capsules and tried to duplicate all of my movements in order to see if I could make it happen again. But it was impossible. The plunger that detonates the bolts is so far out of the way that I would’ve had to reach for it on purpose to hit it – and this I did not do. Even when I thrashed about with my elbows, I couldn’t bump against it accidentally. It remained a mystery how that hatch blew. And I am afraid it always will. It was just one of those things.”27

|

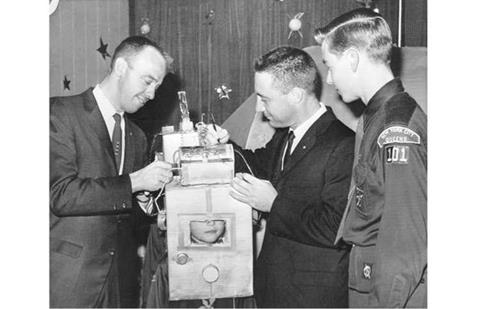

Four days after the MR-4 mission, a McDonnell engineer occupies a test capsule showing an astronaut’s position in relation to the explosive hatch detonator, seen above his head. (Photo courtesy the Kansas Cosmosphere and Space Museum) |

ON TO GEMINI

As of 15 July 1962, Grissom was promoted to the rank of major. Four days later he proudly received the Gen. Thomas D. White Trophy as the “Air Force member who has made the most outstanding contribution to the nation’s progress in aerospace.” Also in 1962, NASA finally moved its manned space flight operations from Langley to the newly built Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) in Houston. The Grissoms were now able to build their first real home, a three-bedroom house in the Timber Cove development near Seabrook.

Following his MR-4 flight, Grissom acted as CapCom for later Mercury flights, but spent a lot of his time in St. Louis assisting McDonnell in the development and construction of the Gemini spacecraft. In October 1962 Deke Slayton also assigned Grissom to supervise the nine Group 2 astronauts in the lead-up to Project Gemini. A practical man, Grissom had understood early on that a second Mercury mission was not on the cards for him, as the remaining astronauts would each be assigned flights that would complete the program. “By then Gemini was in the works,” he wrote in his memoir, “and I realized that if I were going to fly in space again, this was my opportunity, so I sort of drifted unobtrusively into taking more and more part in Gemini.”28

Grissom then turned his efforts to the Gemini spacecraft and specifically the layout of the cockpit controls and instrumentation. He was instrumental in having everything laid out as a pilot would like; so much so that the spacecraft soon became known as the

|

Gus Grissom is congratulated by Air Force Secretary Eugene M. Zuckert on being presented with the Thomas D. White trophy. (Photo: UPI) |

|

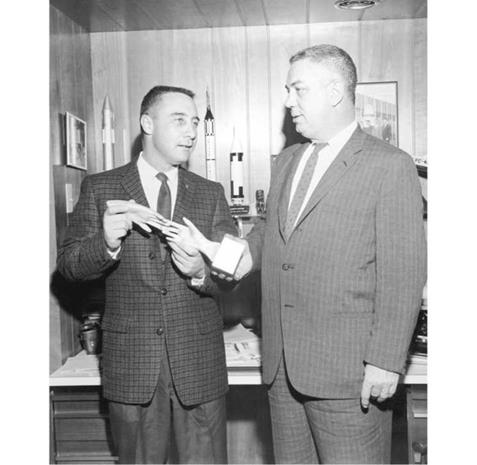

Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom autograph an improvised space helmet made by a New York Boy Scout. (Photo: NASA) |

“Gusmobile.” However, later in the program taller astronauts such as Ed White and Tom Stafford complained that although the arrangement might have been ideal for Grissom’s compact five-foot seven-inch frame, it was something of a tight squeeze for them.

As recalled by Betty Grissom, “Gus was living with the Gemini spacecraft, putting the flier’s touch on the vehicle in which men might live and maneuver in space for days or weeks. At the McDonnell plant in St. Louis he sat in the mockup for hours, day after day, testing each switch and control knob, applying the aviator’s instinct which would guide engineers and technicians in making the machine more flyable and habitable. Although his advice usually was quiet and brief, the engineers never doubted that he meant business, and never forgot that the inanimate mass of metal, wiring and black boxes was a flying machine to carry men from Earth and back again. In fact, they were laying bets that Gus would be the first to fly it.”29

Then, in April 1964 Grissom’s diligent work was rewarded when he received his second mission assignment as commander of the first Gemini two-man mission. The official announcement came on 13 April, five days after the successful launch of the unmanned Gemini 1 capsule. He was the first astronaut to be officially assigned to a second space flight.

|

Among many other honors, Grissom received a presentation trophy from the U. S. Junior Chamber of Commerce as “one of the ten outstanding young men of 1961.” (Photo: NASA) |

Wally Schirra, selected as the Gemini-Titan 3 (GT-3) backup commander along with co-pilot Stafford, was delighted that his Mercury colleague and friend had been given the first flight assignment, saying that he felt Grissom now had something to prove. “He was angry about being blamed for his spacecraft having sunk, and he was fighting to come back out of the pack. Gus was a tiger. He wanted the first Gemini flight, and by God he got it.”30

|

Grissom shows his trophy to NASA Operations Director Walt Williams. (Photo: NASA) |