“GRISSOM DID NOT BLOW THE HATCH”

When asked if he’d had much of a chance to discuss the loss of Liberty Bell 7 with Grissom on Grand Bahama Island or afterwards, helicopter pilot Jim Lewis replied, “We saw several of the astronauts at GBI, including Gus, but other than shaking hands and passing momentary pleasantries, I didn’t see Gus again until working at MSC in Houston.

“We really never discussed MR-4. I think we had moved on, and both of us knew we had followed nominal and contingency procedures properly. I had received two commendations for my actions that day and [later] Gus was subsequently selected to command the first Gemini and Apollo missions. No greater vote of assurance could have been given to him.

“We both knew he had done nothing to cause the door to detach itself that day, and we both knew we would not be able to find out specifically what happened, so there was little to discuss. Our conversations revolved around the present and future, and I’ll guarantee you we had plenty to keep us occupied. The work in those days was exhilarating, intense, long, and hard… and, great fun.”14

|

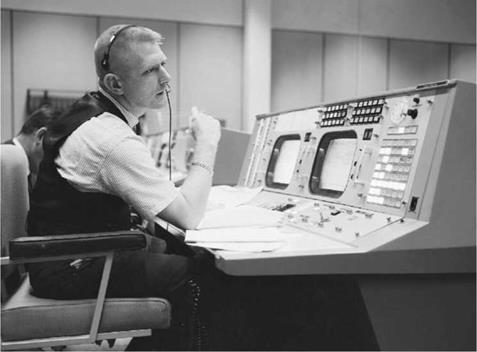

Flight Director Gene Kranz at his Mercury Control Center console. (Photo: NASA) |

The agency’s near-legendary flight controller Gene Kranz always set the tone in launch control with his calm, confident and professional manner. He would display very little emotion in the thick of a mission and he always remained focused on the tasks that lay ahead, like a general before a battle. He was not one to quibble or stay silent if he felt someone had underperformed, and he is quite adamant that Grissom did not blow the hatch.

“I spent a lot of time with Gus,” Kranz stated. “Everybody alleges that the guy panicked. Gus is not the kind of guy who would panic… he is a very controlled person. I also knew we had an inherently different hatch design, from the standpoint of a release mechanism, to the other [Shepard] one. I knew the limitations in testing, and if Gus says he didn’t do it, then he didn’t do it. It’s that straightforward.”15

Another front-line exponent of Gus Grissom was McDonnell engineer Guenter Wendt, who helped insert Grissom and the other early astronauts into their spacecraft prior to hatch closure. Wendt, who died in May 2010, was a staunch admirer of Grissom. “We cannot prove what happened,” he told interviewer Jim Banke in June 2000. “It was an unexplained anomaly. But we know that Grissom did not blow the hatch.”

|

Former McDonnell Pad Leader Guenter Wendt (Photo: NASA) |

Based upon his interview with Wendt, Banke later wrote that to detonate the ordnance, either Grissom would have had to firmly bang his wrist on a plunger inside the capsule, or a recovery diver alongside the spacecraft in the water could move a small panel on the outside and pull a T-shaped handle in the event that the astronaut was disabled. Later experience would show that if a Mercury astronaut were to detonate the hatch from the inside, the amount of force necessary to hit and activate the plunger would leave a nasty bruise, which Grissom didn’t have.

It was put to Wendt that perhaps the switch on the outside of the capsule was accidentally pulled. Wendt responded with a theory that the small panel on the outside of Liberty Bell 7 might have broken off as the spacecraft deployed its main parachute or shortly thereafter. In one transmission to Alan Shepard in the Mercury Control Center, Grissom said “you might make a note” of the fact that there was a six-by-six-inch hole in the parachute which Wendt said approximated the size of the access panel. Then, after splashdown, Wendt believes something may have tugged on the exposed handle just enough to cause the hatch to blow – perhaps a parachute line or a line associated with the green dye markers deployed from the capsule after splashdown. It is a known fact that after Grissom quickly egressed from the sinking spacecraft he reported becoming tangled in a marker line outside the hatch.

“That is the one [possibility] that I believe in,” Wendt concluded. “It is the most logical explanation. Can we prove it? No.”16

When asked to characterize Gus Grissom in the light of later criticism of him and his actions that day – particularly in the movie adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s book, The Right Stuff – Jim Lewis expressed his particularly strong recollections and feelings.

“Gus flew 100 combat missions in Korea. He was a successful test pilot. He had been selected to be an astronaut. Many applied, few were chosen. He was selected to fly the second manned U. S. space mission. He was later selected to command both the first Gemini mission and the first Apollo mission. Those kinds of things do not happen to a ‘screw up.’

“That kind of person would never have survived combat or been a test pilot, and would not have been selected to be the first in line to blaze the way for new space programs… Gemini and Apollo. NASA obviously had confidence in Gus. I am sad that Wolfe and his media apparently chose to ignore what, to me, is the obvious. I went through the same flight school as Gus – a bit later – flew in the Far East, and was an engineering test pilot. Nothing in Wolfe’s book about flight school or the MR-4 mission or flying in general was characterized the way I would have chosen. but Wolfe neither interviewed me nor asked my opinion.

“In addition, think about this. MR-4 had a large window – the first spacecraft to have such – adjacent to the hatch. When the capsule was floating, Gus looked right out that window and could see water above the hatch sill and above the lower edge of the window, which was lined up with the lower sill of the hatch. Do you think anyone would have purposefully released a hatch under those conditions? I would add that since we had practiced such things, he also knew that I wasn’t there yet and obviously hadn’t lifted his spacecraft clear of the water. So then, did he accidentally hit the release? NASA records show that every astronaut who used that plunger to release a hatch got a bruise or skin abrasion from the rebound of the plunger. Gus’s post-flight physical documented that his body was totally unmarked. This is positive evidence that he did not ‘accidentally’ hit that plunger. Had he done so, he would have been even less able to escape its rebound than any of those who actuated it on purpose.

“Gus was a consummate pilot, a very bright individual, and a skilled engineer who had everyone’s respect. No one who knew him could or would argue with that statement, and that is how he should be remembered.”17