CELEBRATIONS CONTINUE

Also facing a barrage of questions from reporters that day was the youngest sibling of the Grissom family, 27-year-old Lowell from St. Louis, Missouri, who worked as a systems analyst for the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, the firm which had made the Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft. He had watched his brother’s successful shot from their St. Louis living room with his wife Bobette, and said that they had finally been able to relax for the first time in fifteen days. “We’re greatly relieved,” he stated. “One more postponement was about all we would have needed.”

Lowell disclosed that his brother had told him by phone fifteen days earlier that he would be the pilot for the next mission, well before the public announcement of Gus’s selection. “I couldn’t tell anyone that Gus would be the pilot,” he said. He also revealed that some top McDonnell officials knew his brother had been named, “but they weren’t talking about it.”

Lowell and Bobette said they only slept “on and off” during the night and were up around 5:00 a. m., “long before the alarm went off.” He said that once the Redstone rose from the launch pad safely he was confident everything would go well. His wife said, “I was really shaken up when they said they had lost voice contact for a time. I suppose Lowell was too, but we weren’t doing much talking during the shot.”

Lowell declined firmly, but politely, to permit newsmen and photographers into their suburban apartment during the space shot, but admitted them once his brother was in the recovery area and ready to be hoisted aboard the helicopter. They were obviously worn down by the two postponements.

“If Gus can stand it, so can we,” Bobette said.3

In Newport News, Virginia, a proud but relieved Betty Moore Grissom said she was “happy” her husband’s flight was a success. “But I’m so sorry the capsule was lost,” she remarked.

In her memoir Starfall, it was revealed that even though Betty knew Gus’s craft had been lost she had no idea how close she had come to losing him. “I didn’t have time to worry if he was safe,” she explained. “The first thing that went through my head was: I hope he didn’t do anything wrong. It was going through my mind, that probably was how the news people would write it. I knew if he had made a mistake he would never forgive himself. My second worry was now I had to go out and meet the press.”

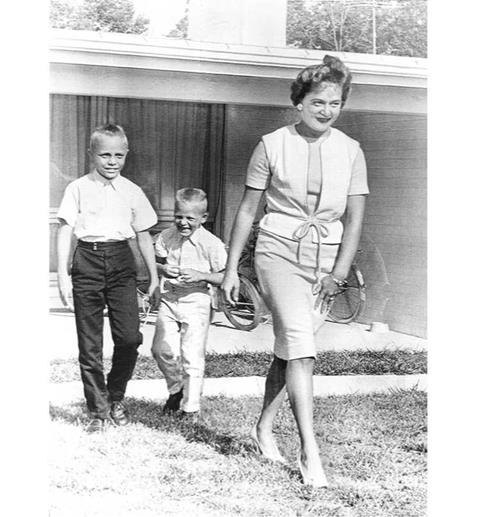

“I’ve always known it would be a success,” she told a dozen newsmen several minutes later on the lawn of her home, perched on the bank of a small lake, perhaps with more confidence than she felt at that moment. Together with their two sons, Scott, 11, and Mark, 7, and with the wives of her husband’s fellow astronauts Deke Slayton, Scott Carpenter and Walter Schirra there to support her, Betty had watched as the dramas unfolded on their television set. She had emerged from her home with Scott

|

Lowell and Bobette Grissom. Lowell was an engineer at the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation where Liberty Bell 7 was constructed. (Photo: Associated Press) |

and Mark shortly after her husband was safely aboard the aircraft carrier USS Randolph. Wearing a light blue dress and a blue and white striped jacket, she was smiling and animated throughout the interview. “We achieved a first today – the boys and I talked by telephone to Gus as he lay flat on his back in the capsule before it was launched. He said if we stopped talking he could go to sleep,” she laughed.

How did the boys feel about their father’s achievement that day?

“Scott clapped his hands when the rocket went up,” Betty said.

“And I whistled too,” Scott remarked, then added he would have liked to have been with his father on the flight.

Responding to one question, Betty said that “the last two seconds before liftoff” were the most concerning moments for her. Asked if she prayed during the flight, she said, “certainly.” She was also asked if she would like for her husband to be the first astronaut to make an orbital flight. “I think I would, because he would,” she dutifully replied.

|

Betty Grissom at their Newport News home with sons Scott (left) and Mark. (Photo: Associated Press) |

When asked about the last time she had seen her husband, Betty replied that she last saw him two weeks before the flight, but had talked to him by telephone daily during that time. “I hope he calls me when he reaches Grand Bahama Island,” she added.

Did she wish her husband was in a less strenuous occupation?

“I’ve always left it up to him to decide what to do,” was her considered response. Space flights were important she observed, but said she “will leave them to Gus and the boys.”

Did her sons wish to follow in their father’s footsteps? She said both boys would probably become pilots.

Finishing up the interview, Betty said, “Now I can rest for a few days and get back to normal.” She planned to spend the remainder of that day “watching television and answering the telephone.”

“And I’ll go swimming,” Scott chimed in. Betty would later state that her interview with the newsmen was “much worse than watching the flight on television.”4