WATERLOGGED, BUT WELL

In a later report for the waiting media, Drs Laning and Strong stated that on arrival, Grissom had immediately received a preliminary physical examination, and blood, urine and other samples had been taken for later analysis. Dr. Strong told reporters that, “Our shipboard examination finds no abnormalities. He is in excellent spirits except that he feels unhappy about the capsule. Both Dr. Robert Laning of the Navy and I are pleased that he is in excellent shape. All tests and observations are within normal limits.”34

Dr. Laning added that Grissom was in just as good a physical shape as Shepard was after his flight, “except that he was a little more tired after the swim.” Laning pointed out that Grissom had swallowed a considerable amount of sea water and was suffering a slight soreness in the throat as a result. He said the astronaut reported he was feeling “a bit shaky” when he first came onboard ship, but soon relaxed and ate a second breakfast that day of orange juice, fried eggs and bacon. The doctor stated that Grissom’s pulse rate was 160 when he first came aboard but it shortly dropped to a near normal 100. “He said he had a thrilling ride,” Laning told the assembled reporters. “He is feeling well.” Laning also said that Grissom asked for a drink of water as soon as he entered the debriefing. “Fresh water, that is,” grinned Laning as the reporters jotted down this little gem of information.35

Once the initial excitement of Grissom’s arrival on the Randolph had died down, and while the astronaut was undergoing his preliminary physical examination, Jim Lewis made an official report to the ship’s skipper, Harry Cook, on his own part in the recovery effort.

Meanwhile, mechanics inspecting Lewis’ helicopter were puzzled, having failed to find anything amiss with the engine. It was later suspected that the chip detector light might have been triggered by a stray metal flake that had somehow worked its way into the engine’s oil sump.

Asked what actions he might have taken if the indicator light had not illuminated while he was struggling to raise Liberty Bell 7 out of the water, Lewis responded, “I would have waited and just hovered with the spacecraft, holding it under water until the recovery carrier arrived. Of course, if that happened, figuring out how to bring the spacecraft aboard the carrier would have been a challenge.”36

|

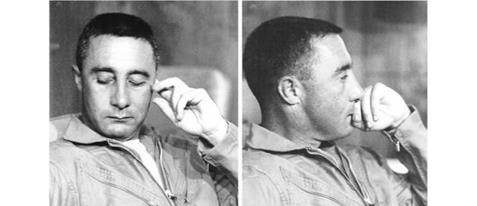

A contemplative Grissom, now wearing his orange flight, shows evident exhaustion as he awaits a flight to Grand Bahama Island. (Photos: Dean Conger/NASA) |

|

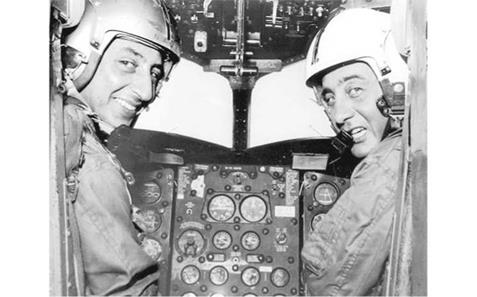

Grissom chats to Capt. Harry Cook as he prepares to fly off the USS Randolph for his debriefing on Grand Bahama Island. (Photo: Dean Conger/NASA) |

Overall, Jim Lewis recalls that everything he experienced onboard the Randolph after he landed was “very businesslike and professional because that is how one is trained in the military. Gus understood all that occurred and appreciated the efforts that were made to bring [the capsule] back. While we all would have preferred to have the spacecraft, what resulted, given the circumstances, represented excellent results.”37 Following Grissom’s physical tests and debriefing it was time for the astronaut and the Marine recovery pilots to board a waiting twin-engine S-2F Tracker airplane and proceed to Grand Bahama Island, where the nation’s newest hero would undergo a far more extensive medical examination and provide a comprehensive account of his flight, along with his recollections of the post-splashdown dramas. At the island facility the four Marine helicopter pilots would also discuss with Grissom and NASA officials what they had observed from above Liberty Bell 7, and attempt to figure out what had led to the loss of the spacecraft.

As he strode over to the flight line with Capt. Cook heading for the S-2F Tracker, Gus was talkative and grinning, and took a moment to wave up to Rear Adm. John E. Clark, who was standing on the bridge. As he reached the airplane, two bells were rung for the attention of all on the carrier and the loud speaker called out, “Captain, United States Air Force departing” – an honor normally only reserved for admirals.

There was another pleasant surprise in store for Grissom courtesy of Capt. Cook as Lewis and Reinhard buckled themselves into two seats in the rear of the airplane. Following a spontaneous request from Cook, and with the agreement of the chief pilot, the Navy co-pilot had happily relinquished his right-hand seat to Grissom.

|

An S2-F Tracker of VS-26 on the Randolph’s elevator. (Photo: VS-26/U. S. Navy) |

As Cook shook Grissom’s hand he gave him this news. As Cook later observed, while Grissom was clearly pleased to make it safely onto the Randolph after his recovery, “he got almost as much thrill… when I invited him to act as co-pilot on the catapult launch of the plane to take him to [Grand Bahama Island].”38

The Navy pilot in command on that brief flight was John Barteluce, who, at the age of 90, still hasn’t lost his lifetime fascination for aviation. In fact, these days he is the oldest crew member of Coast Guard Auxiliary Flotilla 10-01, whose airplanes fly security patrols each day, extending from the Canadian border to the Manasquan Inlet. “I’m going to go on as long as I can,” he told an interviewer in 2012.

Grissom left the carrier by plane for Grand Bahama Island just 77 minutes after stepping onto the deck from the recovery helicopter.

When asked to comment on the events of 21 July 1961, Barteluce told the author, “Needless to say I was happy to be chosen to fly Grissom from our carrier to Grand Bahama Island. Gus was elated that I asked him to be my co-pilot and experience his first and only takeoff from an aircraft carrier.

“It was a fairly short flight and the conversation was mostly about his asking me about my background. I told him that I was a fighter pilot flying F4F Wildcats from the baby carrier USS Nehenta Bay [CVE-74] during World War II.”

One of Barteluce’s most prized possessions is a Dean Conger photograph of him flying alongside Grissom on their way to Grand Bahama Island, which the astronaut later signed for him.39

Meanwhile, a press conference was being held at NASA Headquarters at which officials were discussing the loss of the spacecraft. Mercury Operations Director Walt Williams told reporters that the only significant records of the mission lost were two

|

John Barteluce and his temporary “co-pilot” Gus Grissom. (Photo: Dean Conger/NASA) |

color-camera films of Grissom and the instrument panel taken during the flight. They showed the movements of his hands and facial expressions, and might have assisted in improving the positioning of some instruments for later missions.

Robert Gilruth, director of the STG, added that most of the desired information was received and recorded through telemetry. He was quick to point out that despite a dramatic and valiant effort to save the capsule, “the vital part of the cargo – the astronaut – was saved.” This sentiment was backed up by another NASA official, who said “We’ve got only one Gus, but we’ve got plenty of space capsules.”

With questions about the end of the flight still to be answered, Gilruth decided to withhold his planned announcement that the MR-4 flight concluded the suborbital segment of NASA’s $400 million man-in-space program, despite there being two suborbital flights listed on the original schedule. He had been expected to say that if everything had worked perfectly, that there was no longer any need to risk the other five astronauts on short but dangerous flights, and the agency would instead start to insert astronauts into orbit using the 300,000 pounds of thrust delivered by the Atlas booster.40

Amazingly, the Mercury flight of Gus Grissom had attracted far less attention than that of Alan Shepard just two months earlier. In one serendipitous exercise, the KWK radio station in St. Louis selected telephone numbers at random on the day of the flight and asked thirty people who answered, “Who is Virgil Grissom?” Eleven correctly identified him as the latest astronaut; thirteen said they didn’t know; three said he was a disc jockey; one thought he was a radio announcer. Another believed him the former tenant of her apartment, “because I got some of his mail.” And one sleepy woman answered, “With this hangover, I couldn’t care less!”41