SAFELY ABOARD

Jim Lewis nursed his helicopter back to the Randolph, later acknowledging he was less concerned about the losing the spacecraft than he was in getting his aircraft and crew back safely to the carrier. After landing, his attention was more focused on the wellbeing of Gus Grissom. Like everyone else, Lewis and Reinhard could only wait anxiously for Upschulte’s helicopter to arrive.

As Don Harter told the author, although the Navy helicopter and its crew had not been needed in the rescue of Gus Grissom, the astronaut still had to be transported over to the safety of the waiting aircraft carrier. “After George Cox had raised Gus into their helicopter we escorted them to the carrier, as their cargo was top priority. By this time Lewis had already landed on the carrier.”25

The second Marine helicopter landed gently on the carrier’s deck at 8:01 a. m., just 41 minutes after Grissom’s Redstone booster had thundered into the Florida skies. Having removed the lifejacket, but still clutching his gloves, a sodden and bewildered Grissom clambered out of the helicopter as soon as it had shut off its engine. The Associated Press reported his first words as, “Give me something to blow my nose. My head is full of water.”

There to greet Grissom and hustle him off to his post-flight debriefing were two military doctors – Navy Cdr. Robert Laning and Army Capt. Jerome Strong. They had both performed the same duty after the recovery of Alan Shepard two months earlier.

Laning and Strong would not only conduct a preliminary medical examination and evaluation of the astronaut, but also guide him in the process of “debriefing,” speaking into a tape recorder and giving his immediate recollections of the flight. The debriefing

|

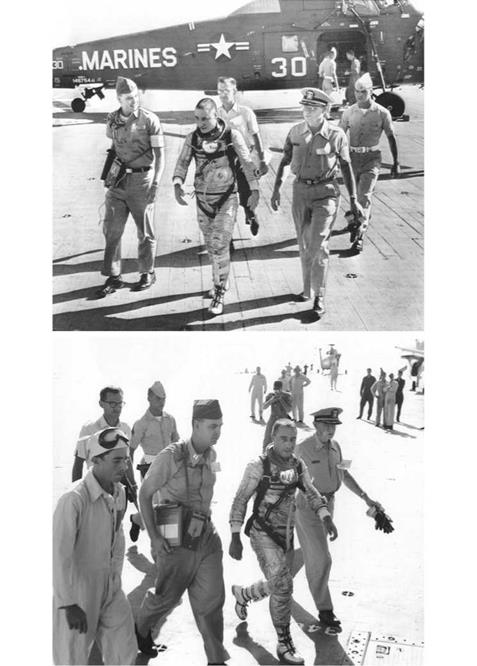

As Grissom is helped from the helicopter by George Cox, Drs. Laning and Strong are ready to assist him onto the Randolph’s flight deck. (Photo: NASA) |

|

Still drenched in sea water, Grissom appears to pump his fist at being safely onboard the recovery carrier. (Photo: NASA) |

would take place in a quiet, air-conditioned and oak-paneled cabin normally occupied by the Randolph’s skipper, Harry Cook. The cabin included a sitting room, a bedroom, a bath, and a small galley.

Before he had a chance to towel off and change out of his water-soaked space suit, Grissom, still dripping water, received a congratulatory telephone call from a relieved President Kennedy.

“Although we were still in the air at the time, we learned the sailors aboard the Randolph were deeply sad over the loss of the Liberty Bell,” Don Harter recalled. “Especially when they saw the helicopters come back without the capsule. However we were proud to be a part of it – a part of history – and the sailors on board cheered as Grissom exited the recovery helicopter, knowing he was safe as he walked across the flight deck while he was being escorted to the debrief.”26

Despite the passage of more than 50 years, Roger Hiemstra has many memories of the day they welcomed America’s second astronaut onboard, although he admits some things have been forgotten with the passage of time. “I remember quite well, though, that very hot and sunny day. We had been primed for the recovery and were kept up to date over the loud speakers. I recall that the flight deck was full of sailors awaiting the recovery. As I knew it could be a long wait and I wanted to get a good location, I had brought a book with me and was sitting on the deck among everyone waiting it out. I do remember a Look or Life photographer was on board and he came over and took a picture of me reading and asked a couple of questions about what I was doing.

|

|

The scene from the bridge as Grissom is escorted across to the doorway leading to the quarters of the ship’s Captain. (Photo courtesy of Otto Preske) |

“I had brought along my old 8-mm camera to take some film, but a chief petty officer soon saw me with it and made me put it away. We clearly saw the parachute when it came into view (we were prompted over the loud speakers on the progress and where to look) and watched the splashdown even though it was perhaps a half mile or more from the ship. Even I, as an E3 Yeoman, could soon tell something was wrong. We could see that the helicopter [pilot] had clipped onto the capsule and was struggling to pull it up – at least it certainly looked like a struggle. As we now know water was pouring in. Then there was what appeared to be a cutaway or breakaway and that helicopter struggled to make it back to the carrier. We were told later that the engine had been just about ruined.

“Then there was action around the second helicopter, which was them pulling in Gus. That chopper made it back to the ship just fine and I can clearly see in my mind Gus walking away from the chopper and into the bowels of the ship through a hatch. He passed by within 20-30 feet of where I was sitting. We (the lower enlisted men) never saw him again and I was so saddened to hear later of his death in the [Apollo 1] fire.”27

Airman Robert (‘Bob’) Bell was also amongst the crowd of spectators gathered on the flight deck of the Randolph for the arrival of astronaut Gus Grissom. “If my memory is correct, I was aft of the number two elevator,” he recalled. “So my view wasn’t all that great. Everyone was kept back from the landing area for both safety reasons and to shield Grissom. He stepped from the recovery helicopter and nearly ran straight to the hatch leading into the island.” Apart from being disappointed at the rapid disappearance of the nation’s newest astronaut, Bell believes Grissom was not in a very good mood and still recalls him as being “not at all enlisted-friendly” to the scores of sailors who had gathered on the deck to witness this historic moment. “He may have been upset over the capsule sinking, but he snubbed the sailors on the flight deck and went straight to the officers’ area. Nothing like the pickup of John Glenn a few months later,” Bell added. “Glenn was a great guy. I still have a slip of paper he signed and dated.”28

Another excited onlooker was radarman/seaman apprentice Mike Andrew, who was up early in the morning at his station on the Randolph’s bridge along with Capt. Cook. After several postponements of the Mercury shot, he was not alone in hoping it would all come together that day.

“At the time, I was a seaman apprentice and the CIC radar representative for Capt. Cook,” he explained. “This was my normal station and we were on our fourth mission attempt to retrieve Gus Grissom and his capsule. Lots of volunteers for my station that morning, but no way was I going to miss this – I didn’t know I had that many friends!

“Spirits remained high and the ‘RAND DO – CAN DO’ attitude was in high gear throughout the bridge crew, especially since we had the best seats in the house. The clouds seemed less intrusive than the past days and there was a feeling on the ship’s island that this was the day after three cancelations. For me, at 20 years old, this was a dream of a lifetime, as space flight was the wave of the future and on the carrier’s island I had the best seat in the house.” There was only one disappointment for Mike Andrew. “I forgot my camera!”

The air of expectancy onboard grew when the sailors learned of the successful launch from the Cape. “Not knowing what was going to happen, all we could do was look towards the heavens and keep an eye on the choppers,” Mike Andrew continued. “Each one of us was eager to be the first to sight the capsule. Finally the capsule appears and settles onto a kinda rough Atlantic Ocean. A while later we see a chopper struggling with the capsule. Soon it returns without the capsule which we learned had sunk, but a second chopper had Gus aboard. Our event ended quickly, as once on deck Gus disappeared. I will, however, always remember the smiles and laughter on the bridge that day. High fives hadn’t been invented yet. Then, back to work for all. We had a ship to sail.”29

In watching footage of Grissom’s arrival on the Randolph, one can understand why he did not think to wave at the surrounding hordes of sailors, or even have time to do so. As he stepped down from the helicopter he was immediately book-ended by Laning and Strong, who quickly ushered the chilled astronaut in his sodden suit across to a nearby hatchway at the foot of the bridge island, asking him questions along the way. Unlike Shepard, who had to traverse a considerable distance of the Lake Champlain’s flight deck, and even turn back to retrieve his helmet from inside his spacecraft, a

|

These two photographs show the recovered parachute canister on the deck of the Randolph. (Photo: NASA) |

soaked and miserable Grissom was closely escorted just a few feet to the open hatchway and disappeared within seconds of planting his feet on deck. Understandably, despite what he had just accomplished, he was not in the best of moods.