CLOSE TO DEATH

As the drama continued to unfold, it was being captured on film by photographers aboard a second Navy helicopter, whose pilot had been instructed to remain well clear of the recovery area. Their dramatic images caught Grissom wallowing in the ocean swell. Every so often, the powerful down draft from the helicopters would momentarily force him below the surface of the water, and then he would bob up again like a cork.

Donald Harter from Columbus, Ohio recalls that day as one filled with many emotions. He was a DC2 (Damage Control, 2nd Class Petty Officer) temporarily assigned to the rescue/recovery team aboard the USS Randolph, and was aboard Navy Sikorsky HSS-1 N No. 52 from Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron HS-7 (“The Big Dippers”). Positioned in the helicopter’s doorway, he witnessed the drama below from close hand.

“I had trained in astronaut recovery previously,” he reflected. “The protocol was to always have two helicopters involved in the recovery of the astronaut and the capsule. There was another helicopter in the area filled with photographers, but they had been warned to keep well away from the recovery effort.

|

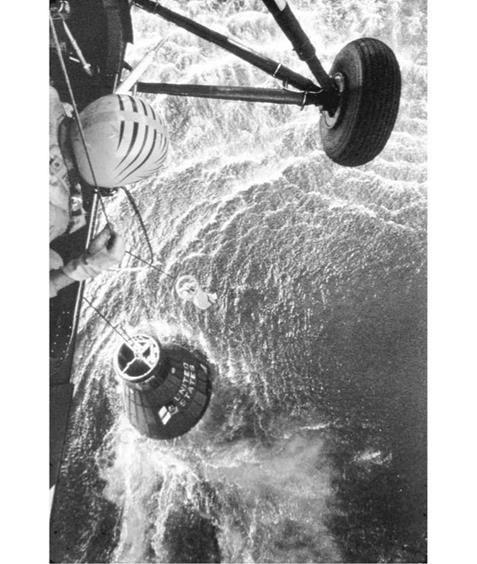

John Reinhard begins to lower a horse-collar rescue sling down to Grissom before the crew’s attempt to raise him was aborted. (Photo: NASA) |

“When Lewis notified that he was returning to the carrier because of possible engine failure, we were dispatched as part of the two-aircraft protocol to assist Upschulte and Cox if necessary. If something unforeseen were to happen, we had recovery gear on board; in fact all the helicopters aboard the carrier had winches on the open side door and safety harnesses.”18

|

Taken from a high-level recovery airplane this photo shows Lewis’s helicopter trying to raise Liberty Bell 7 while Upschulte approaches Grissom from behind. They are flanked by a Navy support helicopter and (nearest the camera) the photographic helicopter. (Photo: NASA) |

Grissom, now struggling to keep his head above water, noticed with alacrity the photographic helicopter in the distance, and would later recall that “I could see two guys standing in the door with what looked like chest packs strapped around them. A third guy was taking pictures of me through a window.” Unbeknownst to them, the photographers might very well have been recording on film the last desperate moments of astronaut Gus Grissom, for as he revealed in We Seven he was now in a fierce struggle just to stay afloat. Flailing about in the water, he knew he could not last much longer.

“At this point the waves were leaping over my head,” he wrote. “I was floating lower and lower in the water. I had to swim hard just to keep my head up. I thought to myself, ‘Well, you’ve gone right through the whole flight, and now you’re going to sink right here in front of all these people.’”19

Grissom then saw to his relief that the backup helicopter was moving in towards him, dragging a horse-collar sling across the surface chop of the water. He was still in danger of drowning, however, since the rotor wash of the two rescue helicopters and the weight of his waterlogged space suit meant that he could not reach the sling, now about 20 feet away.

Sensing Grissom’s problem, Phil Upschulte flew a little further forward, dragging the horse collar right up to the astronaut, who was also swimming towards the sling. Despite his fatigue, Grissom looked up and saw the familiar face of George Cox leaning out of the doorway. The Marine pilot had earlier been involved in successful ocean recoveries of both Alan Shepard and the chimpanzee Ham. “As soon as I saw Cox, I thought, ‘I’ve got it made,’” Grissom later reflected. Now close to complete physical exhaustion, he was able to grab hold of the lifesaving collar. “I had a hard time getting it on,” he reported at his post-flight technical debriefing, “but I finally got into it.

|

Upschulte and Cox finally retrieve an exhausted Grissom from the ocean. (Photo: NASA) |

A few waves were breaking over my head and I was swallowing water.” In fact, he was so exhausted that he could do little more than pass his arms through the lifesaving collar, not caring that it was on backwards, and hang from it.

By this time Grissom had been swimming or floating in the choppy seas for four or five minutes, “although it seemed like an eternity to me,” he reflected later. In a departure from procedure, he was dragged 15 feet through the water prior to being hoisted into the air with water streaming from his space suit until he was able to be assisted into the cabin of the helicopter.20

Don Harter, watching from nearby Navy helicopter No. 52 remembers the scene well. “We arrived just before [George] Cox had lowered their harness to Gus. We backed off so as not to prop-wash Gus, and let Cox complete the recovery, but still near enough to give assistance. Gus had to swim for the horse collar, with swells going over his head. The NASA helicopter with the photographers who had been waving at Gus while he was trying to stay alive left and returned to the carrier.”21

Prior to a waterlogged Grissom being hoisted into Upschulte’s helicopter, Jim Lewis had been faced with an incredibly difficult decision.

“I was pointed into the wind at this stage and the backup helicopter was behind me, also pointing into the wind to give added lift, so I could no longer see Gus. But as we had communication between aircraft, the pilot of the backup craft let me know when he had Gus aboard. Gus was safely aboard and on his way to the Randolph in less than four minutes after the hatch blew on Liberty Bell 7, so you can see that our contingency procedures worked perfectly. This is exactly why we had the backup helicopter close at hand.

“After close to five minutes of pulling maximum power [on my helicopter], the cylinder head temperature began to rise and the engine oil pressure began to drop. I decided to release the capsule, so I could set the helicopter down ‘normally’ in the water if the engine died. That was accomplished by pulling a trigger in the cockpit that caused the hook to open and release the recovery cable from the helicopter. I couldn’t see the line but I could feel the result of a reduced payload. I wondered if we could make it back. I declared an emergency at that point, and proceeded back toward the Randolph, and was able to land aboard the carrier.”22

Once onboard Upschulte’s helicopter, Grissom shed the horse-collar, and shook Cox’s hand with a heartfelt, “Boy, am I glad to see you.” Then he grabbed a nearby Mae West life preserver and slipped it over his head. While this might have been standard over-the-water military procedure, he was simply ensuring he was ready in case anything happened to the craft he was now occupying. Once was enough, he figured: he had no wish to endure any more time splashing around in the Atlantic trying to stay afloat. As he fastened the Mae West he was told that his capsule had been lost. He then spent the duration of his ten-minute flight over to the Randolph without speaking, tightly buckled up in the lifejacket.

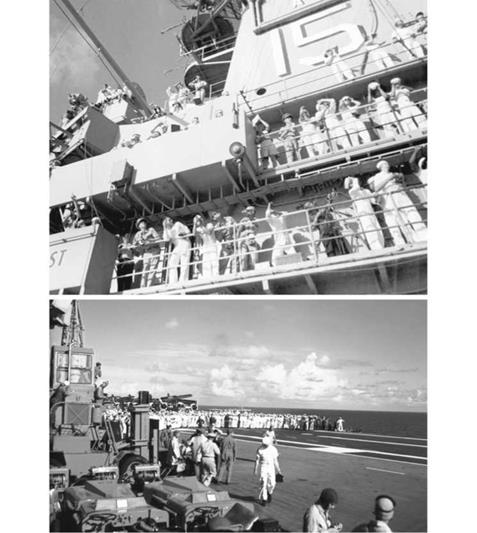

Meanwhile, on the USS Randolph, Capt. Henry (‘Harry’) E. Cook, Jr. had been made aware of the problem as Lewis’s helicopter was straining to lift Liberty Bell 7 out of the water. “The capsule was filled with sea water and so heavy it just couldn’t be lifted,” he said, looking back to that time. “I was preparing to launch boats to lash on to it and tow it alongside and then use the ship’s boat crane to hoist it aboard.”23 When word passed around the nearly 1,000 crewmen lining the afterdeck and the superstructure of the Randolph that the capsule had sunk, there was a brief chill as those watching the drama out at sea feared Grissom himself might have been lost. But the Navy quickly made it clear that the astronaut was safe. Several hundred sailors, including midshipmen from various universities undergoing reserve officer training, were lined up behind ropes on the flight deck of the carrier. But this time there was less of the joyous whooping and hollering that marked the scene on the USS Lake Champlain when Shepard came aboard that carrier. Perhaps this relative quietness was due to the observers silently offering thanks that the astronaut had made it.

Meanwhile, back in the Mercury Control Center, everyone was tense, waiting to find out what was happening. They had heard that Grissom was in the water, but the conversation on Chris Kraft’s communication line was becoming confusing.

|

Anxious crewmembers aboard the USS Randolph scan the skies as they wait for news on the fate of the astronaut and his spacecraft. (Photos: NASA) |

“We didn’t know what had happened to Gus,” he later wrote. “After a minute of silence, a second helicopter reported that they were ‘attempting to recover the astronaut.’”

“What does that mean?” someone innocently asked Kraft.

At that Kraft snapped, and loudly told everyone to just shut up and listen.

“I remember thinking, I hope it’s not a body they’re recovering,” Kraft related. “The next minute dragged on forever. Then we heard it. Gus was aboard the chopper. They were returning to the ship.”24