ASTRONAUT OVERBOARD!

Recovery procedures now meant that Lewis and his co-pilot Reinhard had the task of cropping off most of the spacecraft’s 4.2-meter HF whip antenna so that it would not interfere with the helicopter’s main rotor when the craft came down to hook onto the lifting loop in the recovery section of the capsule. The telescopic antenna had been automatically deployed when the spacecraft landed, and was there to provide long – range communications and emit a signal for a contingency recovery in the event of the capsule coming down well away from the planned splashdown zone.

As Grissom had landed in the planned pickup zone the antenna was no longer needed, and the procedure was to cut most of it off before the helicopter moved in. This was accomplished using shears similar a tree pruner, attached to the end of a long pole. The co-pilot’s job was to reach down and sever the antenna using this implement. Once he had hooked onto a strong Dacron loop located at the top of Liberty Bell 7, the pilot would apply sufficient engine power to hoist the capsule around 18 inches until the base of the hatch was clear of the water. Finally, they would lower the rescue sling to a position just above the spacecraft and relay this information to Grissom. The astronaut would then disconnect his helmet (thereby ending communications), power down the spacecraft, blow the hatch, and wait for the rescue collar to appear. He would then carefully egress through the hatch and insert his arms into the loop at the foot of the sling. Apart from the use of an explosive hatch, this was the same procedure that had worked so well for Shepard.

As he awaited further instructions, Grissom suddenly heard a dull thud. Without warning, the spacecraft hatch was gone – blown off and out into the ocean. “There wasn’t any doubt in my mind as to what had happened,” he would report in his later debriefing.11 Grissom looked up in shocked disbelief, not only seeing blue sky, but the unnerving sight of salt water spilling over the bottom of the door sill and into the spacecraft.

Grissom knew from previous experiments that once water reached the lower edge of the hatch opening, a Mercury spacecraft could sink in just ten seconds. “I made just two moves,” he later remarked, “both of them instinctive. I tossed off my helmet and then grabbed the right edge of the instrument panel and hoisted myself right out through the hatch.”12 Moments later he was in the water and being thrust away from Liberty Bell 7 by the fierce rotor wash of the helicopter amid a tumult of noise and a rolling Atlantic swell.

In shock, Grissom tried to swim backwards away from his spacecraft, watching with mounting horror as seawater continued to pour in through the open hatch. Co-pilot John Reinhard was equally surprised as Grissom “swam out of the capsule and swam away.”13

Grissom then discovered he had become tangled in a dye-marker line that was wrapped around his shoulder. The line was attached to the spacecraft and he knew that if he could not free himself there was the very likely prospect of being dragged down with the spacecraft if it sank. He finally managed to disentangle himself and moved away from the line.

Somewhat comforted by the fact that he was floating well above the water line and treading water in his buoyant space suit, Grissom was more concerned with the pilot’s efforts to hook onto Liberty Bell 7, which was rapidly settling into the water. “As I got out, I saw the chopper was having trouble hooking onto the capsule. He was frantically fishing for the recovery loop. The recovery compartment was just out of the water at this time and I swam over to help him get his hook through the loop.”

By this time the helicopter was directly over the spacecraft, but with all three of its wheels dangerously in the water. “I thought the co-pilot was having difficulty in hooking onto the spacecraft and I swam the four or five feet to give him some help,” Grissom later stated. “Actually, he had cut the antenna and hooked the spacecraft in record time.” 14

Those who ever doubted the bravery and tenacity of Gus Grissom have obviously not viewed the film footage of what happened next. Battered by the ferocious force of rotor wash and whipped-up water, his immediate concern was not for himself but for his spacecraft. He was not sure whether the helicopter was fully hooked onto the

|

|

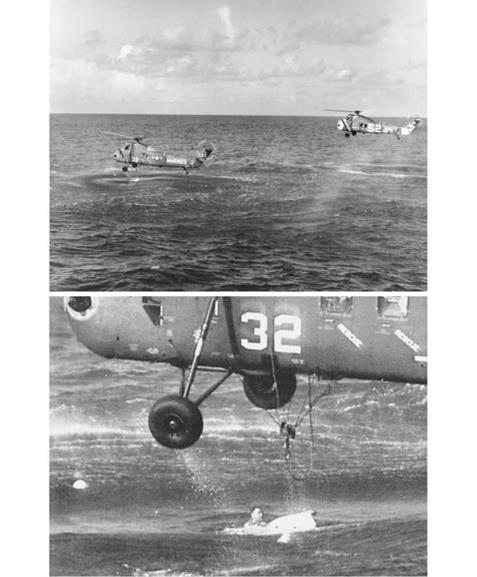

As Hunt Club 1 hovers dangerously low overhead, accompanied by a Navy support helicopter, Grissom checks to see that they have a solid hook onto the spacecraft’s recovery loop, which is just above the water. An enhanced view of Grissom from the same photograph shows his courageous efforts to ensure the retrieval of Liberty Bell 7. Note his helmet floating in the sea at top left. (Photos: NASA)

|

Taken from film footage of the recovery efforts, this still frame shows Grissom trying to hold Liberty Bell 7 upright as Hunt Club 1’s wheels dip into the ocean. (Photo from NASA footage) |

spacecraft’s Dacron recovery loop, which was perilously close to being submerged. He actually reached out and checked this, and then pushed back from the spacecraft, giving John Reinhard a quick double thumbs-up to indicate that they were properly hooked up. At this time, only a few inches of the very top of the spacecraft could be seen above the water. It was an incredible act of sheer bravery and guts which could so easily have cost him his life, and demonstrated that despite the circumstances, Gus Grissom was not lacking in a test pilot’s greatest attributes – his coolness and courage under extreme peril.

As he watched, all the time being forced away from the scene by the downdraft, Grissom knew that things were not going well. “The helicopter pulled up and away from me with the spacecraft and I saw the personal sling start down: then the sling was pulled back into the helicopter and it started to move away from me.”15

Expecting as a result of previous recovery training that the astronaut should stay comfortably afloat in his space suit, and therefore was not in any immediate danger, Jim Lewis concentrated on saving the spacecraft from sinking to the bottom of the sea.

Meanwhile, Grissom suddenly realized that he too was sinking ever deeper in the water which, fortunately, was not all that cold. The neck dam was working well, so that was not the problem. It had been designed and tested by fellow astronaut Wally Schirra specifically to prevent water entering a floating astronaut’s space suit, and it probably saved Grissom’s life that day. But he realized that in his haste to evacuate from Liberty Bell 7 he had neglected to lock the midsection oxygen inlet port on his space suit. This was allowing the air in his suit to bleed out and seawater to seep in. With every second that passed he was becoming increasingly heavier and sinking ever lower in the churned-up seawater. He reached down and locked the suit inlet connection to prevent further water penetration.

|

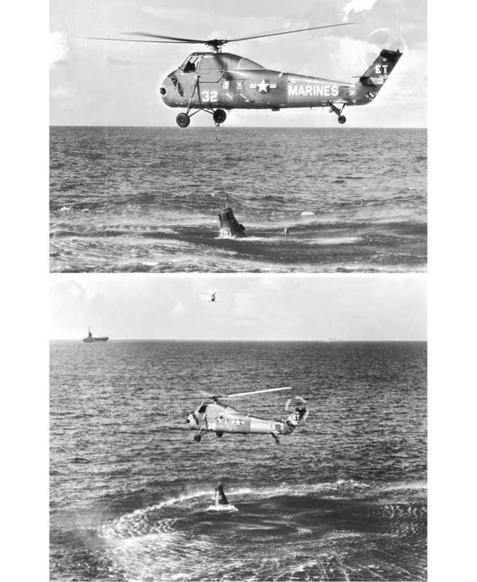

Hunt Club 1 manages to partially raise the spacecraft as Grissom looks on. In the lower photo the USS Randolph can be seen in the distance. (Photos: NASA) |

Now struggling hard to stay afloat, Grissom also recalled some souvenir items he had stuffed into the left leg of his suit. These comprised of two rolls of fifty dimes, some miniature models of his spacecraft, and a small wad of dollar bills. “They were added weight I could have done without,” he later confessed, even though the weight was actually quite minimal.