AT THE READY

On the morning of the second launch attempt, as with the postponed liftoff two days earlier, a number of fixed-wing aircraft were flying at high level along the Atlantic missile range in order to assist with the location and recovery of the spacecraft as it broke through the clouds and splashed into the ocean near Grand Bahama Island.

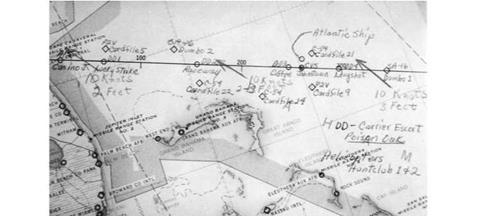

The primary recovery chart for Grissom’s mission specifies two P2V Neptune airplanes from the Navy’s Patrol Squadron 5 (VP-5) based at NAS Jacksonville, Florida, call-signed that day Cardfile 5 and Cardfile 9. They had SARAH (Search and Rescue and Homing) equipment on board operated by either Navy or Air Force personnel as appropriate, and there was usually a NASA/STG representative. Not shown on the recovery chart was a third P2V call-signed Cardfile 23. Piloted by Navy Cdr. Lester Boutte, its assignment was to take up position in the predicted recovery zone, spot the spacecraft as it descended on its parachute and then circle high at high level to observe the recovery efforts. In addition there were two C-54 Douglas Skymasters call-signed Cardfile 21 and Cardfile 22, and a pair of SA-16 Grumman Albatrosses designated Dumbo 1 and Dumbo 2.

The three P2Vs had taken off at staged intervals beginning at 2:00 a. m. In addition to the aircraft flown by Lester Boutte, one was under the command of Lt. Cdr. Edward McCarthy, whose assignment was to fly near the Cape Canaveral launch site, ready to assist in the event of an early booster malfunction over the ocean. A third P2V was operated by Lt. Cdr. Anthony Ruoti, and was stationed downrange from the planned landing site for use in the event of an overshoot.

Cardfile 23 pilot Lester Boutte had been involved in a much-publicized rescue operation some 19 years earlier in November 1942, after a B-17D had been shot down over the Pacific. Boutte, then a radioman aboard a scouting two-man Navy OSTU Kingfisher, had spotted a life raft adrift in the ocean twenty days later, when any hope of finding survivors had all but gone. The survivors, many near death, were rescued and carried to safety – some even strapped to the small aircraft’s wings – by the Kingfisher’s pilot, Lt. William Eadie, USN, who taxied across the water to a rescue ship. One of those lucky survivors was famed World War I air ace Eddie Rickenbacker.

Also on board Cardfile 23 as an observer of the MR-4 flight was the STG’s Milton Windler. Back then he was a member of the Landing and Recovery Test Section headed by Peter Armitage, one of the Canadian AVRO engineering group that went to work for the newly established space agency NASA. In 1967 he was transferred into Flight Control and served as lead flight director for several Skylab and lunar missions, including Apollo 13 and Apollo 14.

“At the time of MR-4 our Recovery Branch was fairly small; twelve in all, headed by Robert Thompson,” Windler reflected. “My job at the time included evaluating, recommending, and testing the Mercury location aids. All of these were activated automatically and required no crew action. This included the SOFAR bombs, HF beacon and the primary aid – the UHF SARAH. This was the same aid as used by the RAF pilots in the Battle of Britain. A very simple, clever scheme. It involved a special receiver and Yagi antennas on the P2V (and other) aircraft. The identical UHF beacon used by the RAF was installed on the Mercury spacecraft.

“We conducted many operational tests and, since I had a lot of experience with these tests, I went out to the primary landing area with the commander of the recovery location aircraft. This was usually (probably always) the senior pilot or aircraft commander for the array. I was there to represent NASA, answer questions and offer advice in the location process, and to provide post mission observations. The aircrews were well

|

Milton Windier, a later lead flight director with NASA. (Photo: NASA) |

|

This map, personally annotated by McDonnell engineer Guenter Wendt, shows the position of all the MR-4 recovery force participants. (Photo: Rick Boos) |

trained and motivated and really needed little help from me however, except to translate some of the countdown events. NASA had recovery branch personnel with most of the ships as well, especially the [carrier] designated to be the primary recovery ship.”2 Apart from the USS Randolph, the prime recovery carrier, other ships involved in the recovery operation were the destroyers USS Conway (DD-507), USS Cony (DD- 508), USS Lowry (DD-770) and USS Stormes (DD-780); the oceanic minesweepers USS Alacrity (MSO-520) and USS Exploit (MSO-440); the tracking ships USNS Coastal Sentry (AGM-15) and USNS Rose Knot (AGM-14); and the salvage and rescue ship with the appropriately name of USS Recovery (ARS-43).