INTO THE WILD BLUE YONDER

Almost before he knew it, Grissom heard Blockhouse 5 capsule communicator Deke Slayton run the clock down to zero and then call “Ignition!” Grissom felt the launch vehicle begin to vibrate and could hear the engines start. Flames burst from the foot of the rocket.

Moments later the elapsed-time clock started and Alan Shepard, the CapCom in the Mercury Control Center, confirmed liftoff. Grissom quickly performed his next duties. “At that time, I punched the Time Zero Override, started the stopwatch function on the spacecraft clock, and reported that the elapsed-time clock had started.”6 Eight seconds into the launch he almost laughed out loud when he heard Shepard cheekily put on his best imitation of comedian Bill Dana – who had a hilarious routine as a reluctant astronaut named Jose Jimenez – warning Grissom, “Don’t cry too much!”

The Redstone left the launch pad gracefully and drove through a clear patch of blue sky before arching over and heading into the Atlantic target area. The powered ascent proceeded well, and was reported to be very smooth. A low-order vibration became noticeable at around T+50 seconds, but did not cause any interference in communications or degrade Grissom’s vision. It quickly dissipated and could no longer be detected by T+70 seconds.

The only problem occurred at this time. One of the carbon jet vanes detached from the Redstone – it can be seen streaking away in footage of the ascent. These vanes, which served as the booster’s steering rudder, were mounted in the lower portion of the booster and extended into the rocket’s engine exhaust. They were used in conjunction with air rudders to control the Redstone’s attitude. During the early part of the ascent

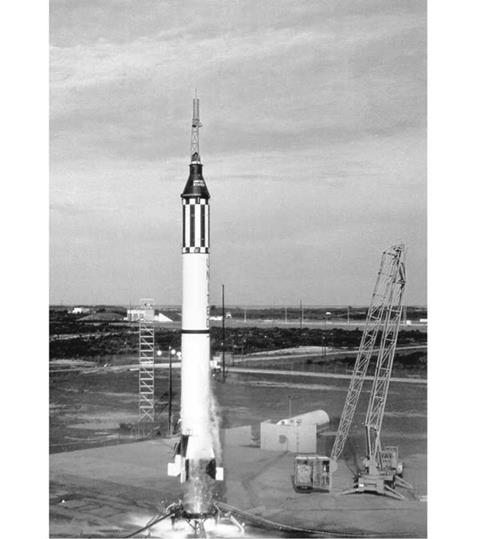

|

Liftoff of the MR-4 mission. (Photo: NASA) |

the Redstone was controlled by the jet vanes, but when the rocket had reached a velocity sufficient for it to become aerodynamically stable, the air rudders took over the control function. The loss of the jet vane at this point did not seem to have any noticeable effect on the stability or function of the booster.

“I looked for a little buffeting as I climbed to 36,000 [feet] and moved through Mach 1, the speed of sound,” Grissom later reported. “Al [Shepard] had experienced some difficulty here; his vehicle shook quite a lot and his vision was slightly blurred by the vibrations. But we had made some good fixes. We had improved the

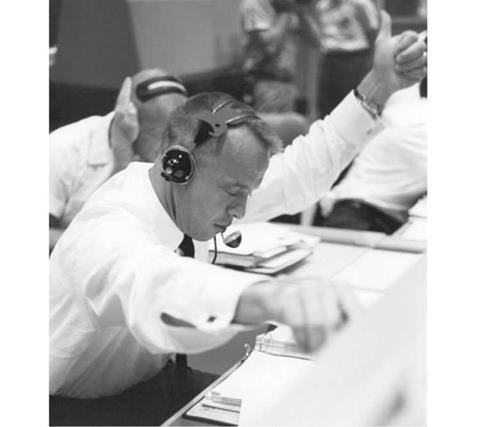

|

In the Mercury Control Center, Alan Shepard signals the successful launch of the Redstone rocket. (Photo: NASA) |

aerodynamic fairings between the capsule and the Redstone, and had put some extra padding around my head. I had no trouble at all, and I could see the instruments very clearly.”7

Whereas Alan Shepard had been restricted to external observations through a periscope device, Grissom had the benefit of the newly installed centerline window and commented that his vision out of the window was good at all times during the launch.

“As viewed from the pad, the sky was its normal light blue; but as the altitude increased, the sky became a darker and darker blue until approximately two minutes after liftoff, which corresponds to an altitude of approximately 100,000 feet, the sky rapidly changed to an absolute black. At this time, I saw what appeared to be one rather faint star in the center of the window. It was about equal in brightness to Polaris. Later, it was determined that this was the planet Venus.”8

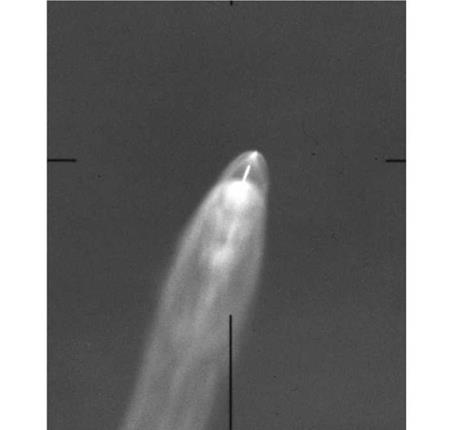

|

The Redstone soars away from Launch Pad 5. (Photo: NASA) |

As the Redstone continued its ascent, Grissom reported that he was receiving a force of 2.5 G. Then, 142 seconds after liftoff, the Redstone’s engine suddenly shut down. Although Grissom reported a slight tumbling sensation and several moments of disorientation, he had experienced similar sensations in centrifuge simulations so he knew what it was and it didn’t trouble him. The sensation occurred once again just ten seconds later when the escape tower clamp ring fired and the tower blasted free of the spacecraft. He later said that the explosive separation and firing of the escape tower was quite audible and he could see the escape rocket motor and tower throughout its tail-off burning phase and for some time after that, climbing off to his right.

|

|

|

|

Back in the Mercury Control Center, Wally Schirra lights a celebratory cigar for Alan Shepard. Partly obscured behind and between them is Joe Walker, one of NASA’s X-15 pilots. (Photo: NASA) |

Grissom was observing the tower when the posigrade rockets of his spacecraft fired on schedule, separating it from the spent Redstone. This was accompanied by “a very audible bang and a definite kick, producing a deceleration of approximately 1 G.”9

On separation from the booster Grissom pitched forward slightly in reaction, but it was an anticipated sensation. At this point, Liberty Bell 7 was coasting upward in free flight.

In his later debriefing Grissom said that, like Shepard, he had to make a special effort to notice that he had entered into a weightless condition. His primary cue was a visual one, which became apparent when he noticed stray washers and some trash floating around; there was no other sensation of zero-g.

“Now, I was on my own,” he later recorded, as he described the view out of his enlarged window. “Shortly after liftoff I went through a layer of cirrus clouds and broke out into the sun. The sky became blue, and then – quite suddenly and abruptly – it turned black. Al had described it as dark blue. It seemed jet black to me. There was a narrow transition band between the blue and the black – a sort of fuzzy gray area. But it was very thin, and the change from blue to black was extremely vivid. The Earth itself was bright. I had a little trouble identifying land masses because of an extensive layer of clouds that hung over them. Even so, the view back down through the window was fascinating. I could make out brilliant gradations of color – the blue of the water, the white of the beaches and the brown of the land. Later on, when I was weightless and about 100 miles up – almost at the apogee of the flight – I could look down and see Cape Canaveral, sharp and clear. I could even see the buildings. This was the best reference I had for determining my position. I could pick out the Banana River and see the peninsula which runs further south. Then I spotted the south coast of Florida. I saw what must have been West Palm Beach. I never did see Cuba. The high cirrus blotted out everything except the area from about Daytona Beach back inland to Orlando and Lakeland, to Lake Okeechobee and down to the tip of Florida. It was quite a panorama.”10