AN UNNERVING INCIDENT

On 24 March, the Redstone rocket had been successfully rated for human use with the completion of the Mercury-Redstone Booster development (MR-BD) suborbital proving flight, carrying a previously flown and unmanned, non-functional Mercury “boilerplate” capsule. However, before a Redstone booster carried an astronaut on a similar flight it was deemed necessary to conduct an orbital test of the Mercury-Atlas combination as a means of checking out the Mercury spacecraft in the actual orbital environment. This MA-3 launch would take place on 25 April. The only subject to be carried on board Mercury spacecraft No. 8 was a mechanical astronaut, known to the NASA astronauts as an “astro-robot.”

For the MA-3 launch, Gus Grissom and fellow astronaut Gordon Cooper were assigned the grandstand spectacle of flying delta-wing F-106A jets over the Cape and keeping company with the Atlas rocket as it gathered speed after liftoff.

“I was to approach MA-3 at 5,000 feet, ignite my afterburner, and climb up in a spiral alongside to observe this early phase of its flight,” Grissom wrote in his memoir, Gemini. “Gordon Cooper would take over from his 25,000 feet level and continue observation of the big bird.”

Grissom then noted that everything seemed to go perfectly on launch day. “To allow me more observation time, it was decided I should go in at about 1,000 feet, keeping about half a mile distant from MA-3 after liftoff. No sweat.”

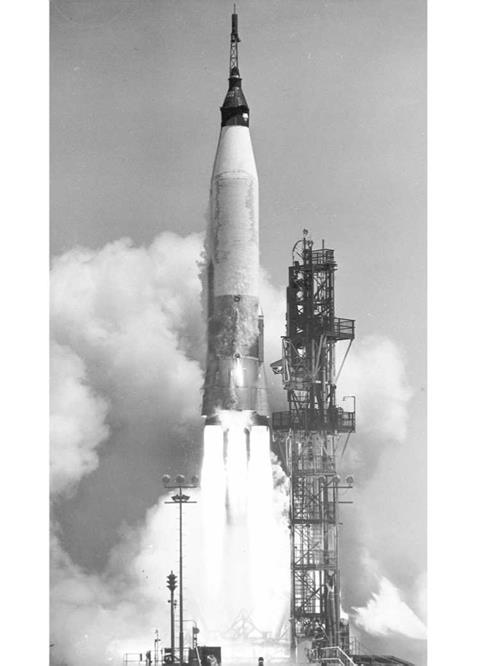

A successful liftoff for the MA-3 mission. (Photo: NASA)

A successful liftoff for the MA-3 mission. (Photo: NASA)

Ignition and liftoff occurred right on schedule, and Grissom was having a dream flight climbing along with the ascending Atlas rocket. As he watched, he saw to his surprise the escape tower fire unexpectedly, prematurely hauling the Mercury capsule away from the Atlas. Things had begun to go seriously wrong when the Atlas failed to follow its pitch and roll programs. At 43 seconds into the flight the Range Safety Officer at the Cape decided to terminate the erratic path of the missile by transmitting the destruct command. This prompted the escape tower to react and haul the spacecraft clear moments before the Atlas blew apart. A shocked Grissom later recorded the scene before him as “Kablooie! The biggest fireball I ever want to see!”

His pilot’s reactions instinctively came into force, and Grissom pulled over and away from the massive explosion, but spectators watching on the ground feared his aircraft had flown straight into the conflagration. A friend later told Grissom he had turned to his shocked wife on Cocoa Beach and mournfully stated, “Well, now there are only six astronauts.”

Gordon Cooper, stationed above at 15,000 feet, was horrified to see the ascending rocket erupt into a gigantic fireball right below his F-106. He later reported that the soaring escape tower and capsule missed his aircraft by what seemed to be 15 feet. Somehow, neither F-106 suffered any damage following the explosion.

Despite the scare, Grissom quickly recovered and decided to follow the released capsule as it descended on its parachute to the water. The test engineer in him had clicked in, and he knew that NASA technicians and others would welcome a report on this phase of the aborted flight. But there was another shock in store.

“I remember thinking, my gosh but these are big seagulls around here today. They were flying all around my plane. And then it hit me – these were no seagulls. They were chunks of the exploded Atlas, falling.” His luck held, as none of the tumbling chunks of rocket hit his aircraft. “It was quite a spectacle,” he noted, “but never again, thanks.”5