THE MAKING OF AN ASTRONAUT

Following his graduation from Test Pilot School, Grissom, now bearing the rank of captain, returned to Wright-Patterson AFB in May 1957 as a test pilot assigned to the fighter branch.

|

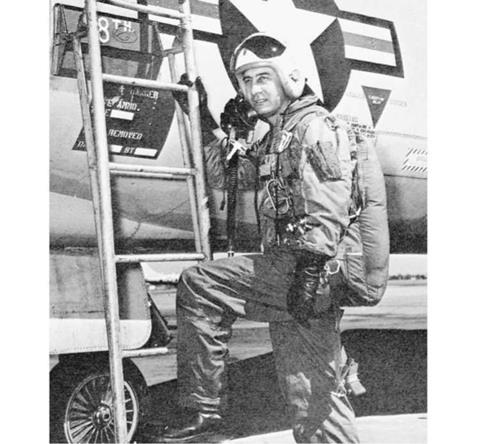

An exultant Grissom after completing his 100th combat mission during the Korean war. (Photo: World Book Science Service) |

One day in 1958, an adjutant handed Capt. Grissom an official teletype message marked “Top Secret,” instructing him to report to an address in Washington, D. C., and to wear civilian clothing. There were no other details, but he knew there was a challenge in there somewhere. As it turned out, he was one of 110 carefully selected candidates who had met the general qualifications for astronaut training. They would undergo initial briefings and medical screening in the quest to find America’s first astronauts for NASA.

After attending the briefing, in which the attendees were given information about Project Mercury, they were offered a crucial choice. If they decided to volunteer for the chance to become what NASA referred to as an “astronaut”, they would move onto the next phase of the selection process. If not, then they could return without prejudice to their present service. Some turned down the chance to be involved

|

Gus Grissom at the U. S. Air Force Test Pilot School, California. (Photo: U. S. Air Force) |

in this new venture. There were too many unknowns and they preferred to continue with the work they were already involved in. Grissom now had to think seriously about his own future.

“It was a big decision for me to make. I figured that I had one of the best jobs in the Air Force, and I was working with fine people. I was stationed at the flight test center at Wright-Patterson, and I was flying a wide range of airplanes and giving them a lot of different tests. It was a job that I thoroughly enjoyed. A lot of people, including me, thought the [Mercury] project sounded a little too much like a stunt than a serious research program. It looked, from a distance, as if the man they were searching for was only going to be a passenger. I didn’t want to be just that. I liked flying too much. The more I learned about Project Mercury, however, the more I felt I might be able to help and I figured that I had enough flying experience to handle myself on any kind of shoot-the-chute they wanted to put me on. In fact, I knew darn well I could.”7

Afterwards, when he told Betty about Project Mercury and the chance that was being presented to him, she said that he would have her full support in whatever he decided to do. After a lot of thought, Grissom decided to volunteer, following which he was subjected to intense physical and psychological testing through early 1959. At one stage he came close to being disqualified when doctors discovered that he suffered from hay fever, and he had to convince them that it would not bother him in space. He argued that he would be sealed in a pressurized spacecraft, with no pollen present. It must have been a close call, as there was a tremendous emphasis on physical fitness. With his usual determination he won his case.

On Thursday evening, 2 April 1959, Gus Grissom received the phone call that would change his life forever. On the other end of the line was NASA’s assistant manager for the project, Charles Donlan, who officially informed him that he had been selected as one of the space agency’s seven Mercury astronauts.

“After I had made the grade, I would lie in bed once in a while at night and think of the capsule and the booster and ask myself, ‘Now what in hell do you want to get up on that thing for?’ I wondered about this especially when I thought about Betty and the two boys. But I knew the answer: We all like to be respected in our fields. I happened to be a career officer in the military – and, I think, a deeply patriotic one. If my country decided that I was one of the better qualified people for this new mission, then I was proud and happy to help out. I guess there was also a spirit of pioneering and adventure involved in the decision. As I told a friend of mine once who asked me why I joined Mercury, I think if I had been alive 150 years ago I might have wanted to go out and help open up the West.”8

Following the announcement of the names of the seven Mercury astronauts in Washington on 9 April 1959, they became instant celebrities – something that caught them (and NASA) completely unawares. “It happened without us doing a damn thing,” Deke Slayton later mused. “We show up for a news conference… and now we’re the bravest men in the country. Talk about crazy!”9