A CHIMPANZEE SOARS

The Mercury-Redstone 2 (MR-2) ballistic flight profile called for the Mercury spacecraft to be boosted to an altitude of approximately 115 statute miles, achieve a period of weightlessness of around 4.5 minutes and a range of approximately 290 statute miles. This time, however, there would be a living creature on board – a freckle-faced, 37-pound chimpanzee that came to be universally known as Ham.

The MR-2 flight was intended to be the final test mission of the Mercury-Redstone launch vehicle, during which a live subject closely related to humans would prove that an astronaut could function without undue difficulty in a weightlessness environment. If successful, the next mission was planned to carry one of the Mercury astronauts. Ham (an acronym drawn from Holloman Aero Medical Research Laboratory, where he got his flight training) was a chimpanzee of normally good nature and alertness, and would be the heaviest animal to be sent into space to that time, either by the Americans or the Soviet Union.

Spacecraft No. 5 had been selected for the mission, and it was fitted with six new systems that had not featured on previous flights: an environmental control system, an attitude stabilization control system, live retrorockets, a voice communications system, a “closed loop” abort sensing system, and a pneumatic landing bag.

|

A landing bag being installed on a Mercury capsule. Note the metallic straps attached to the heat shield. (Photo: McDonnell Aircraft Corporation) |

With Ham securely sealed within a special life-support container inside the capsule, Spacecraft No. 5 lifted off from Launch Pad 5 on 31 January 1961, and landed in the Atlantic Ocean 16 minutes 39 seconds later. While essentially successful, several problems had plagued the flight. The Redstone booster over-accelerated, resulting in an earlier than expected depletion of liquid oxygen. This initiated a signal that caused the escape tower to pull the capsule free just a few seconds before it would have released normally. The overall result was that the spacecraft flew higher and over a longer range than anticipated.

Despite these problems, Ham stoically completed his assigned tasks. The spacecraft splashed down near the Bahamas, landing out of sight of the waiting recovery forces. Some 12 minutes later the first automatically generated signals were received,

|

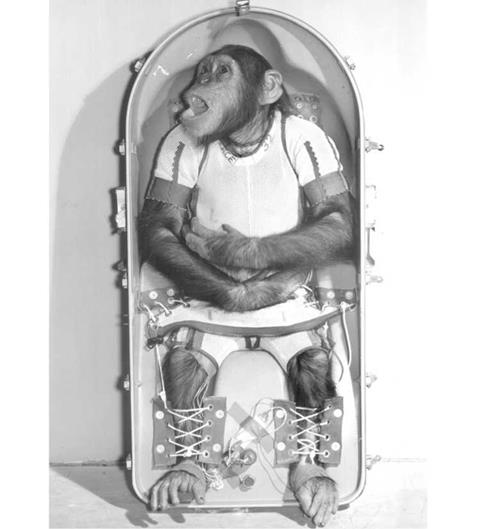

Chimpanzee Ham in his protective couch prior to the MR-2 flight. (Photo: NASA) |

establishing that the spacecraft was about 60 miles from the nearest recovery ship. A search plane sighted the capsule soon after, floating upright in the ocean. When helicopters arrived they reported that the capsule was now tilted on its side, partly submerged, and seemed to be taking on water. It was later found that on impact with the water the lowered beryllium heat shield had bounced up against the bottom of the capsule, punching two holes in the titanium pressure bulkhead before tearing free. An open snorkel valve was also allowing sea water to enter the capsule. Although Ham was secured within his airtight container, it might easily have ended up as his coffin at the bottom of the Atlantic.

A helicopter crew finally latched onto the spacecraft and delivered it to the deck of USS Donner (LSD-20). When the spacecraft was opened, Ham appeared to be in good condition despite a little bewilderment at the attention and some wobbliness in his legs. Apart from that he was quite okay; he passed an onboard examination with flying colors and his appetite was certainly unaffected when he hungrily devoured some fresh fruit.

John King of the space agency’s Public Information Office at the Cape summed up Ham’s 420-mile ride through space. “Ham was going along on a pretty hectic trip, when, just one second before the end of thrust, the Redstone was burning too fast so the automatic abort system functioned. Ham got an immediate jolt of about 17G. We have a movie of it all, and he wasn’t too happy when this occurred, but the amazing thing was that he griped a little, then went right back to work pushing his little levers. It was a tremendous break for the medical people. They got excellent data from this test.”40

With many malfunctions occurring during the flight of chimpanzee Ham, it was prudently decided that the Mercury-Redstone combination was still not ready for the human passenger planned for MR-3. Despite the protests of many, the first human-tended flight was postponed pending a final Mercury-Redstone booster development flight, designated MR-BD.

Although the Soviet Union’s space program was a largely unknown factor back then, in all likelihood their space chiefs would have attempted to launch a cosmonaut ahead of the United States, regardless of which Redstone flight was to carry the first American astronaut. Barring a pad explosion, the Soviets would have raced to beat an advertised launch date for the MR-3 mission, even if it meant launching the day before. They took risks, but their rocket was much more reliable as a launcher than its American counterparts. In retrospect, the decision to insert the MR-BD flight into the schedule could have ultimately cost America the prized goal of sending the first man into space, and caused a lot of consternation for the astronauts and other program participants.

Many felt that Wernher von Braun had been a little overcautious in ordering a primate test flight, and then an additional unmanned suborbital test flight prior to committing America to a manned launch. The MR-BD mission introduced after Ham’s troubled ride helped to push the first flight of an astronaut into May – and allowed Soviet space scientists a little extra time to prepare for their own surprise space spectacular.

As a consequence of the problems encountered on the MR-2 mission, steps were taken to correct the problems on the now-added MR-BD flight, which would test the effectiveness of all the modifications that resulted. Carrying a boilerplate Mercury capsule loaded with a mannequin astronaut and an inert escape system, Redstone MRLV-5 roared off Launch Pad 5 at 12:30 a. m. on 24 March. With the spacecraft remaining attached as planned to the Redstone throughout the suborbital flight, the entire assembly followed the desired trajectory, achieving a peak altitude of 113.5 statute miles and a downrange distance of 307 statute miles.

This time there were no plans to recover the booster or spacecraft, which, still attached, plunged into the Atlantic Ocean at the end of a near-perfect mission. The whole operation had gone so well that there was no longer any reason to delay the much-anticipated MR-3 mission early in May.

|

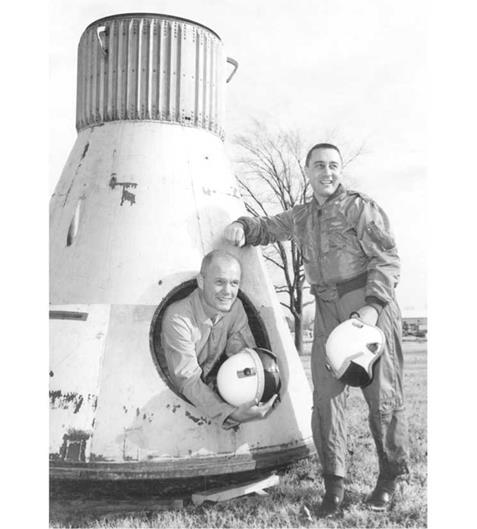

John Glenn and Gus Grissom pose with a boilerplate replica of a Mercury capsule. (Photo: NASA) |

Everything was now set for an as-yet-unnamed American astronaut to become the first person to fly into space.

However, on 12 April 1961 it was a Russian cosmonaut named Yuri Gagarin who grabbed that honor and glory with a single-orbit flight around the Earth. NASA, and the American people, were stunned and mortified. Perhaps none more so than Navy Cdr. Alan Shepard, who had earlier been secretly chosen to make the first flight of a human being into space.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— >-

In July 1961 all seven astronauts visited the McDonnell plant in St. Louis, Missouri. Back row, from left: Gus Grissom, James S. McDonnell, Alan Shepard and Scott Carpenter. Front row: Walter Burke (Vice President, McDonnell Aircraft), Gordon Cooper, Deke Slayton, Wally Schirra and John Glenn. (Photo: McDonnell Aircraft Corporation)

|

A pensive Wernher von Braun in his Huntsville office (Photo: NASA) |

|

|