THE FIRST MERCURY-ATLAS SHOT

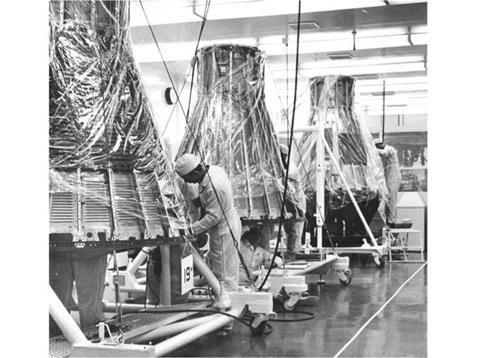

By July of 1960 there were close to a hundred McDonnell people employed at the Cape, and things were moving ahead rapidly as the first full-configuration Mercury spacecraft was to be delivered there on 24 July. In order to keep all the spacecraft free from dust or other intruding contamination, the vehicles were all delivered to the Cape in clear plastic sheathing and transported to another clean room within Hangar S. This particular capsule was Spacecraft No. 2, destined to fly on the unmanned MR-1 test flight of the Redstone/capsule combination. Prior to this, Spacecraft No. 4, which had been delivered to the Cape on 23 May, was due to ride an Atlas rocket for the MA-1 proving flight.

The MA-1 spacecraft shell had been loaded with around 200 pounds of sensing instrumentation, installed by NASA Langley. As with the earlier Big Joe launch, there

|

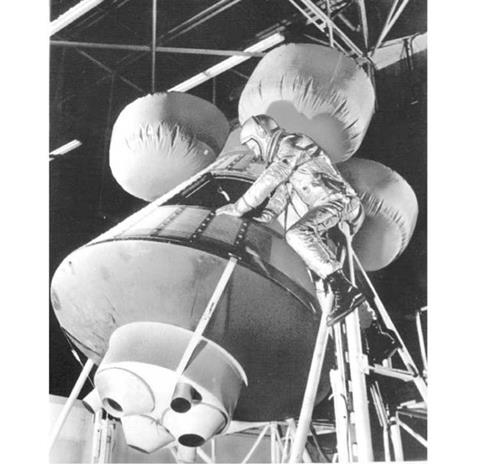

Langley engineers practice water egress techniques using replica capsules that are surrounded by inflated air bags. (Photos: NASA/Langley Research Center) |

was no escape tower attached to the capsule, much to the dismay of the Atlas rocket people who had wanted a complete configuration in order to determine the structural bending modes of the Atlas. However, Max Faget was strongly against installing an escape tower, deeming it unnecessary, and he won out. In the end, the Mercury-Atlas launch turned out to be a disaster, as recorded by Luge Luetjen.

“With the hangar tests completed and the flight instrumentation, parachutes, and pyrotechnics installed, Spacecraft No. 4 (MA-1) was moved to the Atlas complex on July 24, the same day that Spacecraft No. 2 arrived at [Hangar S]. Rainy weather made it difficult to complete preflight checks at the pad and caused delays and much consternation for the NASA officials there for the launch.

“The day before the scheduled date for the launch, a group of us, several in rain gear, visited the Atlas pad. The next day, early on the morning of July 29, heavy rain

|

Boilerplate capsule SC-5 floats in the Gulf of Mexico off the U. S. Navy School of Aviation Medicine, Pensacola, Florida. Assisted by Navy frogmen, Gus Grissom is photographed practicing egress techniques through the top of the mockup capsule. (Photo: NASA) |

enveloped the Cape but the cloud ceiling soon rose high enough to be considered acceptable for launch. [John] Yardley and I were invited to be blockhouse observers. Finally, at 9:13 a. m., [NASA Operations Director] Walt Williams gave the OK to launch and the Atlas rose slowly from the launch pad. It pierced the cloud cover in seconds and the initial phases of the launch appeared normal. Then everything went wrong. Speculation had it that the Atlas either exploded or suffered a catastrophic structural failure. Whichever it was, it occurred at about 32,000 feet and a velocity of about 1,400 feet per second. It was indeed a sad day for Mercury!”32

After a thorough examination of all the available evidence and telemetry it was concluded that the Atlas booster had failed in the thin-skin area below the adaptor which joined the spacecraft to the booster. As a result, a stainless steel reinforcing “bellyband” was developed that wrapped around the boosters until later Atlas rockets could be manufactured with a thicker skin incorporated into this critical area.

|

Completed Mercury spacecraft with protective covering at McDonnell’s St. Louis plant. (Photo: McDonnell Aircraft Corporation) |