MOVING TO THE CAPE

In a McDonnell inter-office memo dated 25 August 1959, Bud Flesh announced that a Project Mercury Operations Group would be established at Cape Canaveral, with the office to become active by 3 September. Flesh stated that the group would be led by Luge Luetjen, Assistant Manager of the Operations Group and Engineer in charge of Technical Integration. His responsibilities included establishing the MAC office, liaising with NASA and other space flight and military authorities, and representing the company on committees set up to oversee Mercury Operations. He would also coordinate Redstone Capsule Launch Procedures with the Missile Firing Laboratory (MFL) and NASA.

Among other responsibilities outlined in the memo, Guenter Wendt was assigned to carry forward all arrangements with the Redstone MFL that were necessary for a coordinated program. In particular, he was to assist Luetjen in the launch procedures coordination and in Redstone missile committees. Wendt had been employed by Luetjen because he needed someone who was “a combination of pseudo-engineer and non-union technician to help in some of the technical areas and still do ‘grunt’ work when required.”28

Writing later on the man who would become affectionately known to all at the Cape as the “pad fuehrer,’ Luetjen remarked that Wendt had “allegedly” been an air crew member in the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) and had worked as a mechanic for Ozark Air Lines before joining McDonnell.

The MAC contingent arrived at Cocoa Beach on 2 September and settled into rooms at the Satellite Motel located north on Highway A1A – the main street of Cocoa Beach – linking the beach area to Merritt Island and the City of Cocoa. The next morning they proceeded to the south gate of the Cape where they were met by an administrative officer from NASA who handed them their official badges and escorted them to Hangar S, where they would occupy the south balcony in an area recently vacated by the Martin Company people involved in the Vanguard project.

Jerry Roberts was one of those assigned to work at the Cape, and he recalls times when he and his McDonnell co-workers had to work long hours, seven days a week,

|

Guenter Wendt with Gus Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 spacecraft. (Photo: NASA) |

|

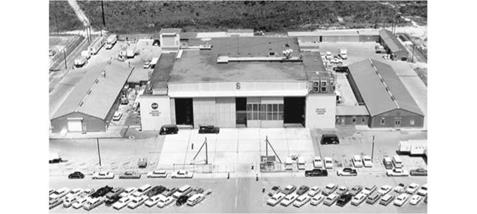

Hangar S at Cape Canaveral. (Photo: NASA) |

often putting in as many as 100 hours per week. “When we first were transferred from St. Louis to the Cape in 1960 it was supposed to be for nine months, and we were going to launch these things initially and then train the NASA people how to launch them, and then we were to come back home. That was pretty evidently not going to happen – NASA had no such capability to even learn from us. They didn’t have the people with the background to take over either part of the program – the missile or the spacecraft – so instead of being down there nine months, some of our people were there till the end of the Gemini program [in 1966].”29

At the time, Operations Director Walt Williams from the STG spoke admiringly of the spirit prevailing at the Cape. “When you have people so well motivated, which they are, you find them working terribly hard and doing really good work. Of course, there should be physical limits. Our people at Cape Canaveral were working 80 to 90 hours a week, which was just too much for them. So we put an arbitrary 60-hour limit on them. Then I found out they were working anyway – just not getting paid for it. This is the kind of dedication we have all through the program”30

|

Atlas 10D on Launch Pad 14 with the Big Joe boilerplate Mercury capsule. (Photo: NASA) |

|

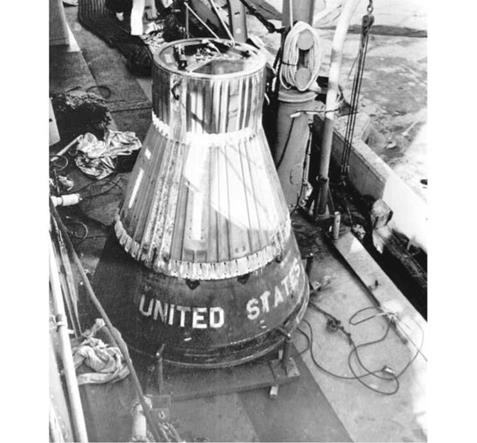

The Big Joe Mercury-style capsule is shown aboard the USS Strong (DD-467) after being recovered from the Atlantic Ocean on 7 September 1959 several hundred miles northwest of the island of Antigua. The top of the capsule held the recovery system during the flight, and was opened to deploy the drogue parachute which slowed the descent of the capsule after reentry and the large main parachute that lowered the capsule to the water. Also visible in the exposed top are the high-intensity marker light and the antenna (folded down) of the search and recovery beacon radios. The small vertical light areas on the side of the capsule are the flush-mounted telemetry transmitter antennas. (Photo: NASA) |

A week after their arrival, on 9 September, the MAC team witnessed the vitally important test launch of Big Joe 1 (Atlas 10D) that sent a 2,555-pound, unmanned boilerplate Mercury capsule on a ballistic arc a distance of 1,424 miles with a peak altitude of 90 miles. This particular capsule was not equipped with a launch escape system. The principal objective of the Big Joe program was to test the Mercury spacecraft’s ablating heat shield, which would be used on the later orbital manned missions. It was also the first Project Mercury flight to employ an Atlas booster. However the booster failed to stage correctly, and separation from the Mercury boilerplate occurred far too late. The capsule was eventually located and retrieved from the Atlantic Ocean and subsequently studied for the effects of reentry heat and any other flight stresses resulting from the 13-minute flight. Despite the booster malfunction, the heat shield had survived the reentry phase and was found to be in marginally good condition. More work needed to be done.

As Luge Luetjen commented, “The telemetry had functioned properly until [the radio] blackout, and as the morning wore on and the spacecraft was recovered and the data reduced, it became obvious that there was sufficient heat pulse to prove the ablation design if the physical examination results were positive. Upon arrival at the Cape, eager eyes focused on the heat shield and marveled at its superb condition. As a result, all plans to use the heavier heat-sink design were scrapped for the rest of the [Mercury – Redstone] program.”31

Indeed, data gathered from the Big Joe 1 flight was enough to satisfy NASA that they could cancel a second launch – Big Joe 2 (Atlas 20D) – that had been planned for the fall of 1959. The launch vehicle manifested for this flight was then shifted to another program.

McDonnell would only miss their optimistic 10-month delivery forecast by two months. Mercury Spacecraft No. 4, planned for the MA-1 test flight, was delivered to NASA on 25 January 1960.

|

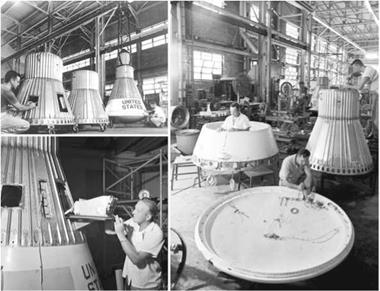

Shown here in July 1959 are Mercury-style capsules specially manufactured by Langley technicians for the Little Joe series of proving flights from Wallops Island, Virginia. While these separate designs were not intended to carry astronauts, they would fly monkeys to test many facets of launch and recovery, including center of gravity requirements and aerodynamic loads. (Photo: NASA/Langley Research Center) |

|

A technician checks a wind-tunnel model of the Little Joe/Mercury capsule combination, circa 1959. (Photo: NASA/Langley Research Center) |