WITH EYES TO THE FUTURE

James McDonnell was someone always looking to the formidable challenges presented by the new frontier of space, as related by former MAC employee Hulen H. (‘Luge’) Luetjen.

C. Burgess, Liberty Bell 7: The Suborbital Mercury Flight of Virgil I. Grissom, Springer Praxis Books, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-04391-3_1, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014

|

In September 1962 President John F. Kennedy visited the McDonnell Aircraft plant in St. Louis. He is flanked in this photo by James S. McDonnell (left) and Sanford N. McDonnell, who became chairman of McDonnell Douglas following the death of his uncle in 1980. (Photo: St. Louis Post-Dispatch staff photographer) |

“Mr. Mac had noted, with passionate interest, what had thus far been done in the space arena and announced that in addition to being the world’s number one producer of fighter aircraft… McDonnell would also become the world’s number one producer of spacecraft – manned spacecraft. He correctly foresaw manned orbital vehicles as being ‘just around the corner.’”1

In making a commencement speech to engineering graduates at the Missouri School of Mines and Metallurgy on 26 May 1957, some five months before the Soviet Union launched the first Sputnik satellite into orbit, McDonnell thoughtfully outlined his expectations for the future of space travel, even giving the students a speculative timetable. Like many others, even though he may have believed that human flight was ‘just around the corner,’ he did not foresee the explosion of interest in human space flight that Sputnik would usher in soon after, and he spoke about the possibility of manned spacecraft orbiting the Earth by 1990. He further predicted that a further 20 years would elapse before there would be a human-tended flight to land on the Moon and return, in about 2010. McDonnell did, however, speak about the escalating threats associated with Cold War tensions, sharing his belief that the United States should instead “wage peace” through the development of dual-use technologies.

“When a chemical rocket motor is developed for a missile, here is a means of propulsion that may be applied in whole or in part to a space vehicle,” he told the graduates. “And, when ways are found for a fighter pilot to survive high gravitational pulls at hypersonic speeds, this will help some future space pilot survive blastoff in a Moon-bound rocket.”2 With this futuristic vision firmly entrenched in his mind, McDonnell had even awarded it the code name of Project 7969.

Early in 1958, following the successful launch and orbiting of the Soviet Sputnik and the massively unsettling impact this achievement had on the American psyche, McDonnell was more eager than ever to explore the possibilities associated with space travel. A substantial start was made when he established a new department similar to the company’s previously established Advanced Design Department (Aircraft), to be headed by L. Michael Weeks, a native of Iowa who had been working on Project 7969 since 1956. Weeks had begun his career teaching mathematics at Iowa State University for three dollars a day before receiving his bachelor’s degree in civil engineering at the university in 1943. He had then gone to work with McDonnell Aircraft in St. Louis, eventually rising to the position of chief engineer. In his time with McDonnell he enjoyed key roles in Projects Mercury and Gemini and would also work on Project Apollo and the Space Shuttle. He was later involved with Rockwell International’s National Aerospace Plane (X-30) and the Orbital Sciences Corporation’s X-34 before retiring after a career spanning 56 years.

The charter for Weeks’s department was highly innovative; it was charged with designing a spacecraft capable of carrying a person through launch and into Earth orbit; sustaining that person in space; safely reentering the atmosphere; landing in the ocean, and remaining afloat until the vehicle could be retrieved.

“Ray Pepping, previously Aircraft Chief of Dynamics, became Weeks’s assistant,” Luetjen recalled, “and John Yardley was named Project Engineer reporting to Weeks and Pepping.”3

John F. Yardley was a veteran of World War II who had completed his undergraduate education in aeronautical engineering, also at Iowa State University. After receiving his master’s degree from Washington University he began his professional career as a stress analyst with McDonnell in 1946. Like Weeks, he would enjoy a long and distinguished career in space flight program development with McDonnell, apart from the years 1974 to 1981, when he joined NASA as the agency’s associate administrator in charge of manned space flight. He then rejoined what was by then McDonnell Douglas, serving from 1988 as senior vice president of the merged company.

In March 1958, ‘Luge’ Luetjen was assigned as Supervisor of Technical Integration under John Yardley. “We knew that studies in many disciplines (aerodynamics, thermodynamics, propulsion, structures, electronics, electrical, design, etc.) would be required,” he observed, “and it was my job to keep all of the disciplines ‘headed down the same path’ and ‘singing from the same sheet of music.’ As I recall, about 50 to 60

|

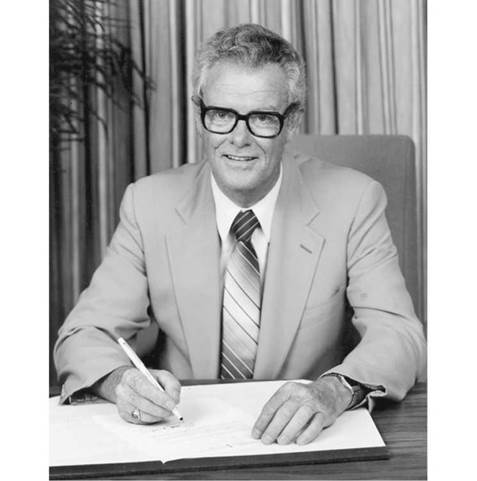

A later photograph of John Yardley. (Photo: Washington University) |

full-time people were assigned to the department in short order, with another 20 or so available to be used on a part-time basis as required. Those assigned were the very top people in the various disciplines. What Mr. Mac wanted, Mr. Mac got! Now all we had to do was produce.”4

Ultimately, James McDonnell’s concept of dual-use technology would play a significant role in his company being awarded a contract to build America’s first spacecraft; one intended for human space travel and Earth orbit.

The concepts of Max Faget 5