AN AUTHENTIC AMERICAN HERO

Prophetically, Shepard called his flight aboard Freedom 7 “just the first baby step aiming for bigger and better things,” but it always galled him that an overdose of caution had cost America (and him in particular) the opportunity to be first in space [5]. His suborbital flight might seem inconsequential when compared with today’s space flights, but at that time it galvanized and united Americans, giving them a renewed sense of pride and accomplishment. It also set in motion mankind’s most audacious scientific undertaking. Just twenty days after Shepard’s triumphant return to Earth, President Kennedy stood before Congress and challenged his nation to land a man on the Moon before the decade was out.

After fellow Mercury astronaut Gus Grissom had virtually replicated Shepard’s flight with a second ballistic flight in July, NASA decided to press on with orbital missions. This was first achieved by John Glenn on board Friendship 7 in February 1962. After two further manned orbital flights by Scott Carpenter and Wally Schirra, it was announced that Gordon Cooper would wrap up the Mercury project with a 22-orbit flight in May 1963.

|

|

|

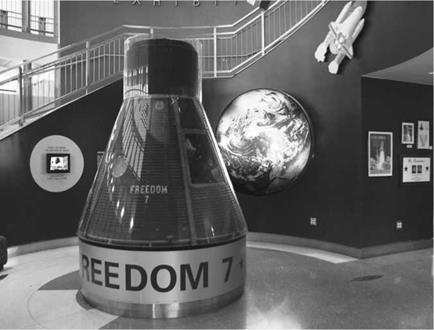

In 1998, following the death of former graduate Alan Shepard, the spacecraft went on longterm display at the U. S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland. (Photo: U. S. Naval Academy)

|

|

Following its arrival in Boston, Massachusetts in 2012, Freedom 7 was delivered to the JFK Presidential Library and Museum as a temporary exhibition. (Photo credit: Rick Friedman, JFK Library Foundation)

|

A smiling Alan Shepard in training for his MR-3 mission. (Photo: NASA) |

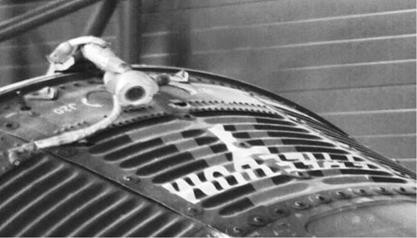

However, Alan Shepard was keen to fly again, and if it meant using a little of his renowned tenacity then he was prepared to give it his best shot. He knew a spacecraft designated 15B had already been manifested to a possible final Mercury mission and it had been substantially upgraded, making it capable of operating a prolonged flight. Since he was Cooper’s backup and his colleagues were now engaged in assignments specifically related to the Gemini and Apollo projects, he would automatically be the prime pilot for an additional flight, if one were to occur. Shepard strenuously argued for such a mission, even renaming spacecraft 15B Freedom 7II, and having that logo painted on its exterior. As NASA was lukewarm to the idea, in a typically audacious move Shepard went around his bosses in the space agency and attempted to enlist the personal support of President Kennedy, who told him that the decision would rest with NASA Administrator James Webb.

Webb carefully weighed up all the options, and when he stood before the Senate Space Committee in June 1963 he began by stating, in part, “There will be no more Mercury shots.” He went on to explain that Project Mercury had now satisfactorily accomplished its goals, and there should be new priorities. All the energies of NASA and its contractors, he said, should now be fully employed in focusing on the Gemini and Apollo missions. As it turned out, even if Shepard had realized his goal of being assigned a second one – man flight, it was a mission he would never have been able to fly.

An early consolation came when Shepard was selected to fly the first Gemini two – man mission, with rookie astronaut Tom Stafford as his copilot. Shortly after starting preliminary training in the simulators in early 1964, Shepard was suddenly struck by an ailment which threatened to end not only his astronaut career, but also his days as a pilot. He awakened one morning feeling slightly giddy, and upon trying to stand up he collapsed. Thinking it to be an isolated incident, he was not overly concerned. But five days later he suffered a second sudden bout of dizziness, and this time began to

|

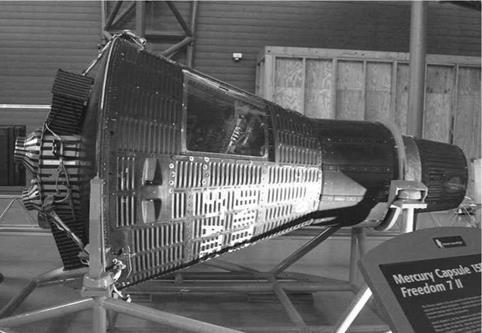

Capsule 15B, unofficially named Freedom 7 II, shown in its orbital configuration at the Udvar-Hazy Center of the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D. C. (Photo courtesy of Stephane Sebile) |

|

The unofficial logo Freedom 7II painted on the side of Spacecraft 15B at the request of Alan Shepard. (Photo courtesy of Stephane Sebile) |

vomit uncontrollably. This incident left him with a loud, recurring ringing in his left ear. After these attacks had struck him down several times, Shepard finally realized it was not something he could simply tough out, and made an appointment with the flight surgeons. After extensive tests, a panel of NASA doctors recommended he be removed immediately from his flight assignment.

The ailment proved to be Meniere’s Syndrome. “The problem is not considered very significant for an Earth-bound person, but it sure can finish you as a pilot,” he said during a 1970 interview for Naval Aviator News. “I convinced myself it would eventually work itself out, but it didn’t. Tom Stafford had told me about Dr. House, out in Los Angeles, who could perform an operation on this particular kind of inner ear trouble. At first it sounded a little risky, but in 1968 I finally decided on having it done. With NASA’s permission I went out to California. In order to keep the whole business quiet, Dr. House and I agreed that I should check into the hospital under an assumed name. It was the doctor’s secretary who came up with it. So, as Victor Poulis, I had the operation, and six months later my ear was fine.” [6]