Splashdown!

It was April 1961 and 20-year-old Air Controlman 3/c (Third Class) Ed Killian from Texas had been serving aboard the Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Lake Champlain (CVS-39) for eighteen months. During that time “The Champ” – as she was fondly known to her crewmembers – had mostly been engaged in an anti-submarine patrol rotation out of NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Towards the end of the month the ship finished a three-week sweep northeast of Norfolk, Virginia, and her exhausted crew were eagerly anticipating some shore leave.

Killian, days away from his 21st birthday, was looking forward to celebrating this milestone in his life in New York City. But then Capt. Ralph Weymouth, the ship’s commanding officer, made an announcement over the ship’s loudspeakers that left Killian’s liberty plans in tatters. Unbeknownst to the crew at the time, however, this change in their schedule would give every man on board the chance to participate in, and be an eyewitness to, an historic event. The ship was to set a new course for the Mayport Naval Station near Jacksonville, Florida. Once there, and after a couple of days, they were to join other units in an area to the east of nearby Cape Canaveral for what was vaguely described as some “special ops.”

“This news of extending the cruise didn’t sit well with the crew in general, and there was a lot of grousing about it,” Killian reflected. “The scuttlebutt was that we were going to do another anti-submarine demonstration for some bigwigs, like the one we had done the previous summer for the Latin American generalissimos and admirals in the Caribbean. Later, while we finished polishing the brass fittings on Pri-Fly’s windows [the control tower for flight operations, known as Primary Flight Control], Cdr. Howard Skidmore, the ship’s Air Officer, known aboard as the ‘Air Boss,’ came in with a big excited grin on his face and told us that the ship was to be the recovery vessel for a space shot from Cape Canaveral. We had heard about the chimpanzee Ham’s flight and recovery in January, and being a recovery vessel for another ‘monkey flight’ held no excitement for us. Such an event was viewed as a poor trade-off for missing liberty in Quonset Point.” [1]

|

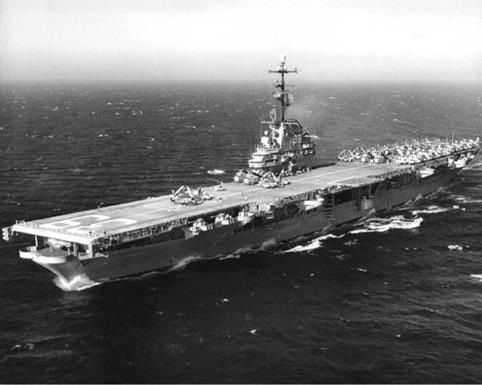

The USS Lake Champlain in 1960. (Photo: U. S. Navy Naval Historical Center) |

CIVILIANS ON BOARD

The crew’s puzzlement grew in Mayport the day after their arrival, with dozens of civilians boarding the carrier. Killian recalls “about fifty NASA and government officials, photographers by the dozen, and boxes of equipment by the hundreds.” Frustration grew amongst the crewmembers, already annoyed at not returning to Quonset Point, who now found their normal routines delayed by these civilians, while the mess hall, already small, was becoming jammed with extra bodies at meal times. Often the line for food wrapped around several frames of the third deck space, creating much grumbling and dissention.

Eventually, Cdr. Skidmore gave his small group of six air controllers in Pri-Fly additional details about the special operation for which the USS Lake Champlain had been selected. As the ship and her crew had performed well in fleet-wide operational competitions, she had been selected as the prime spacecraft recovery vessel for the United States’ first manned space shot, then scheduled for 2 May.

The recovery task force was actually comprised of several task groups, each under an individual commander, dispersed along the projected track of the spacecraft. The task

|

Ed Killian on board the USS Lake Champlain before liberty in Charlotte Amalie, U. S. Virgin Islands, in February 1961. (Photo courtesy of Ed Killian) |

group in the predicted landing area was commanded by R/Adm George P. Koch, Commander, Carrier Division 18, flying his flag aboard the USS Lake Champlain. A crucial element of the recovery task force was a flotilla of destroyers commanded by R/Adm Frederick V. H. Hilles. In cooperation with fellow flag officer Koch aboard the USS Lake Champlain, Hilles would exercise his command of the destroyers from the

Recovery Control Room located at NASA’s Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral. The units of this group were:

|

Name |

Type |

Commander |

|

Aircraft carrier |

||

|

USS Lake Champlain |

CVS-39 |

Capt. R. Weymouth |

|

Destroyers |

||

|

USS Decatur |

DD-936 |

Cdr. A. W. McLane |

|

USS Wadleigh |

DD-689 |

LCdr. D. W. Kiley |

|

USS Rooks |

DD-804 |

Cdr. W. H. Patillo |

|

USS The Sullivans |

DD-537 |

Cdr. F. H.S. Hall |

|

USS Abbot |

DD-629 |

Cdr. R. J. Norman |

|

USS Newman K. Perry |

DD-883 |

Cdr. O. A. Roberts |

|

Minesweepers |

||

|

USS Ability |

MSO-519 |

LCdr. Larry LaRue Hawkins |

|

USS Notable |

MSO-460 |

Lt. Freeland |

|

Salvage and recovery |

||

|

USS Recovery |

ARS-43 |

LCdr. Robert Henry Taylor |

|

Tracking ship |

||

|

USAF Coastal Sentry |

T-AGM-50 |

– |

Two of the six destroyers were positioned 100 miles or more from the USS Lake Champlain, between Cape Canaveral and the projected recovery area, but the others remained in close contact with “The Champ.”

As planned, the aircraft carrier departed Mayport and sailed into position for the recovery operation about 300 miles east-southeast of the Cape. However, inclement weather forced the launch to be delayed, and there was a further delay two days later before the countdown finally picked up again on the morning of Friday, 5 May.

Because of their advantageous view from Pri-Fly, Cdr. Skidmore had arranged for those who worked there to pool their film with NASA photographer Dean Conger. A well-respected photographer for the National Geographic magazine, Conger was “on loan” to NASA as one of the official photographers to record the recovery operation. Appreciating the historic nature of Alan Shepard’s flight, Skidmore set up extensive photographic coverage by positioning volunteer officers and enlisted men at different vantage points on the ship so that the recovery could be recorded on film. When this innovation was combined with the work of the NASA photographers, it resulted in a magnificent, sweeping coverage of the occasion.

After discussing the expected capsule retrieval with senior crewmembers of ships in the recovery Task Force, NASA Space Task Group representatives Martin Byrnes, Robert Thompson, and Charles Tynan determined that the ship’s crewmen assigned to handle the spacecraft were not fully trained in the specifics of what was expected of them, so they initiated a brief education program for the crew. This included the provision of printed information sheets and screening a film on the recovery of the capsule containing chimpanzee Ham earlier that year. According to This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury, published by NASA, “Tynan also carefully briefed each man charged with capsule-handling duties on his particular role.” [2] The carrier’s

|

NASA Recovery Team Leader Charles I. Tynan, Jr. (seated), briefs the USS Lake Champlain’s recovery team officers on spacecraft retrieval. Standing with his hands on his hips is Richard Mittauer, a NASA Headquarters Public Affairs Officer. The Executive Officer of the ship, Cdr. Landis Doner, is at center rear. (Photo courtesy of Ed Killian) |

recovery team consisted primarily of enlisted crewmembers led by the Flight Deck Officer and a number of enlisted Chief Petty Officers of the Air Department; none of whom were at the Tynan briefing. Those in attendance were senior officers who then gave orders and instructions to the carrier’s recovery team. Strangely, not even the Air Officer who led the Air Department was invited to the Tynan briefing.