A DAY FOR HISTORY

It was 1:10 a. m. when flight surgeon Bill Douglas gently woke Shepard. “Come on, Al,” he said. “They’re filling the tanks.”

Shepard had only been asleep for three hours, but was instantly awake and alert. “I’m ready,” he replied. “Is John awake?” Douglas saw that John Glenn was already clambering out of his bed, ready for whatever the day would bring.

“John’s awake,” Douglas confirmed. “We’re all awake. Did you sleep well?”

Shepard said that he had slept soundly and had no recollection of any dreams. He added that upon awakening around midnight he had peeped out through the window to see if it was still raining. “The stars were out and I went back to sleep,” he pointed out with a slight smile. The weather, he was told, was indeed looking good.

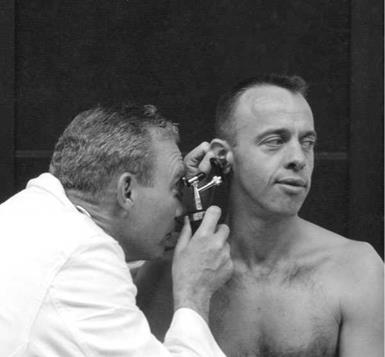

Whistling quietly to himself, Shepard walked to the bathroom where he shaved and showered, then in company with Dr. Douglas and Glenn polished off a breakfast of filet mignon, eggs, orange juice, and tea. “I left the breakfast table to place myself at the mercy of the doctors,” he subsequently recorded, “who did their usual poking, prodding, and measuring, and then attached a battery of sensors to me.” [11] While Douglas and Grissom remained with Shepard, Glenn dressed and went to the launch pad to once again check out the spacecraft.

|

Dietician Capt. Jean McKay serves a launch-day breakfast to Shepard and Glenn. (Photo: NASA) |

|

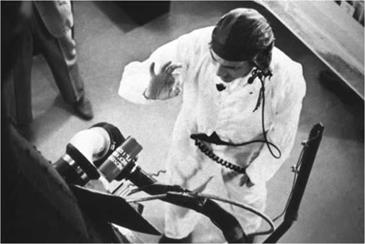

Astronaut physician Lt. Col. Dr. William Douglas inspects Shepard’s ears. (Photo: NASA) |

|

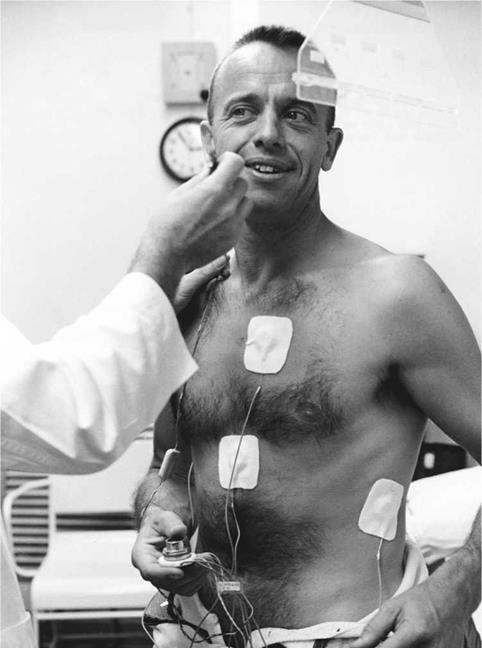

Shepard undergoing a thorough physical examination. (Photo: NASA) |

Altogether, the medical and psychiatric assessments took a little under two hours, but they showed that Shepard was in excellent physical and mental shape for the flight. He had a slight sunburn on his shoulders from staying out in the Sun too long at a swimming pool, and a blackened toenail from Grissom accidentally stepping on his foot a few days before. Most importantly, his respiration and blood pressure were good, while his pulse rate was measured at 75 beats per minute.

The psychiatric examination lasted around an hour, at the end of which the psychiatrist reported, “He realized the dangers he was about to face, but showed no fear. Never seen a man so calm. I tried to get him to talk about other things than the flight, about his family, for example, to see whether this would make him anxious, but I didn’t succeed. All his mind, every nerve, was concentrated on the flight: nothing else interested him. Even while on his way to the suit room he was already a part of the spacecraft.” [12]

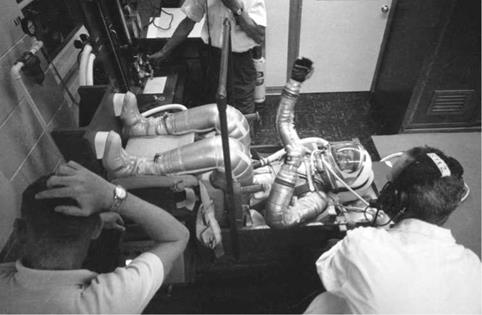

Shepard was then assisted in donning his space suit. Dee O’Hara had already been busy that morning assisting Bill Douglas with his medical checks and procedures, and she vividly recalls the suiting-up time for Shepard. “I remember when he walked into the suit room to get suited up, it was just… everything became dead silent, just became very quiet, and Deke was there, and everybody just sort of milled around, and not much was said. There was hardly any conversation. Joe Schmitt did his checks, and

|

Sensors were taped to predetermined positions on Shepard’s body. (Photo: NASA) |

|

Suit technician Joe Schmitt makes final adjustments to Shepard’s gloves. (Photo: NASA) |

Alan was getting into his boots and, you know, whatever… but it was just dead quiet that day.” [13]

Observing this lengthy process, Bill Douglas was mentally drawing comparisons with an earlier event. “I don’t quite know why,” he reflected, “but it reminded me of the dressing of the matador before the corrida. An astronaut and a matador have nothing in common, but once I was in Spain and I was present at the dressing of a matador and the atmosphere was the same: a solemn anxiety, a religious silence, a lot of people around him. And over everything a vague smell of death.” [14]

Once Shepard was clad in his suit and helmet, a pressure check was carried out by technician Joe Schmitt. Once its integrity had been verified, the suit was deflated; it would not be reinflated until just prior to launch.

At 3:55 a. m., carrying his portable air-conditioning unit, Shepard began to make his way downstairs. Footage from the ABC network television coverage shows Dee O’Hara in a window above the exit. She accompanied him as far as the hall, where he turned to her and said, “Well, Dee, here I go.” Then he followed Joe Schmitt out through the hangar door.

“I was very, very frightened,” O’Hara revealed to the author. “Particularly when he left and went downstairs to get to get in the van. I didn’t know if I was going to see him again, and I just… I straightened up the area.” [15]

Immediately that the hangar door was opened, flashbulbs began to pop and TV cameras followed the astronaut in his silvery suit as he walked behind Schmitt to the small transfer van and cautiously stepped in. They were joined by Bill Douglas, Gus Grissom, and several technicians. Joe Schmitt was there to assist Shepard into his restraint harness once he had been inserted into the capsule.

|

Suit technician Joe Schmitt checks the pressurization of Shepard’s space suit, with Dr. Douglas (with Station 2 headset) observing the procedure. (Photo: NASA) |

Forty minutes later, the van pulled up alongside the launch gantry, essentially a modified oil derrick. It was the same launch pad from where America’s first satellite, Explorer 1, was launched into orbit some three years earlier. There was still some time to kill before he could enter the capsule. Gordon Cooper entered the van to give Shepard a final update on the weather and on the positions of the recovery ships. “He said the weathermen were predicting three-foot waves and 8-to-10-knot winds in the landing area, which was within our limits,” Shepard later recorded. “We had a device in the van to check on the sensors, and everything was working fine. I rested my weight in a reclining chair while all this was going on.” [16]

In order to ease some of the nervous anticipation felt by all in the van, Al and Gus spontaneously broke into their favorite Bill Dana routine, with Shepard playing the role of the reluctant astronaut, Jose Jimenez. Part of the well-known routine involved Jose listing all of the qualities an astronaut ought to have, such as courage, perfect vision, and low blood pressure. Then he finished with, “And you got to have four legs.” Grissom, playing the straight man, asked, “Why four legs?” Shepard grinned widely, and in his best Jose imitation responded, “They really wanted to send a dog, but they thought that would be too cruel!” It did the job, and Shepard was in a good mood when he was informed that it was time to leave the van [17].

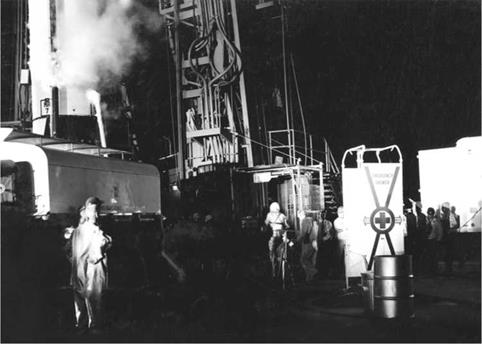

The door was opened, and Shepard carefully climbed down four steps onto solid concrete. Above him the sky was still dark, with a thin sliver of Moon peeping out from small dark clouds. Bright searchlight beams cut back and forth, while arc lights vividly lit the area. But he only had eyes for one thing that morning. He took in the

|

|

gleaming Redstone emblazoned in the brilliant glare of the searchlights, rimmed with frost and ice and gently issuing swirling vapors of liquid oxygen. Around the foot of the rocket, moving through the clouds of vapor, dozens of engineers and technicians were engaged in final preparations, wearing construction hard hats of various colors to denote their work.

|

Shepard steps down from the transfer van. (Photo: NASA) |

|

Gazing up at the Redstone, Shepard pauses on his way to the gantry elevator. (Photo: NASA) |

“I stepped out into a strange world of glaring floodlights and banshee wails from a breeze blowing across supercold fuel lines,” Shepard would later recall. “I looked up, for the moment overwhelmed by the gleaming blue-white lights. Then I began the final walk toward the gantry elevator. ‘Up’ was six stories above me.” [18]

Then Shepard paused at the gantry base, along with Grissom and Dr. Douglas. He shaded his eyes with his left hand and looked up, taking in the sight of the rocket that he would soon ride into the heavens.

“I sort of wanted to kick the tires – the way you do with a new car or an airplane. I realized that I would probably never see that missile again. I really enjoy looking at a bird that is ready to go. It’s a lovely sight. The Redstone with the Mercury capsule and escape tower on top of it is a particularly good-looking combination, long and slender. And this one had a decided air of expectancy about it. It stood there full of LOX, venting white clouds and rolling frost down the side. In the glow of the searchlight it was really beautiful.” [19]

After boarding the elevator at 5:15 a. m., Shepard turned and waved at the launch team, who were cheering loudly and applauding. He had meant to stop and express his thanks, but the emotion of the moment got to him. As they ascended the 70 feet to the level known as “Surfside 5” where he would ingress Freedom 7, Bill Douglas unexpectedly handed Shepard a small gift from a good friend, NASA engineer Sam Beddingfield. It was a box of crayons. They’d once shared a joke about an astronaut about to start a long mission who had taken along a coloring book to help him pass the time, but refused to fly when he found that he had forgotten his Crayolas. “Just so you’ll have something to do up there,” Douglas said with a wide smile. Shepard laughed as he handed the crayons back, saying he might just be a little too busy to use them.

They exited the elevator and made their way into the green-colored gantry room (curiously known as the “White Room”) where the spacecraft stood ready for him to climb in through the two-foot square hatchway and prepare to make history. Shepard

|

Shepard, Douglas, and Grissom board the gantry elevator (Photo: NASA) |

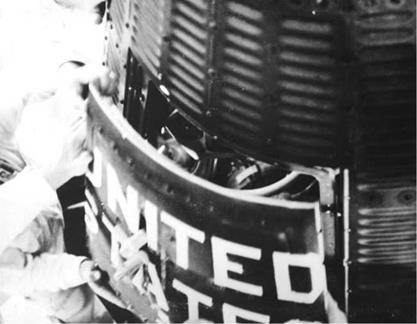

walked around a little, talking briefly with Glenn and Grissom, thanking them for all their hard work, especially Glenn – now wearing a pristine white coat and cap – who had served as his backup pilot. As he moved over to the hatch, he looked once again at the unadorned name boldly painted on the side of his spacecraft. “My choice,” he would explain. “Freedom because it was patriotic. Seven because it was the seventh Mercury capsule produced. It also represented the seven Mercury astronauts.” [20]

At 5:18 a. m., after Glenn had made a final visual check of the spacecraft interior, Shepard gripped his hand in a hearty handshake, and then began the delicate task of inserting himself into the cramped confines of the capsule. McDonnell engineers first assisted the astronaut in removing his protective overshoes, then he lowered the visor of his helmet and wormed feet-first in through the hatch.

“My new boots were so slippery on the bottom that my right foot slipped off the right elbow of the couch support and on down into the torso section, causing some superficial damage to the sponge rubber insert – nothing of any great consequence, however. From this point on, insertion proceeded as we had practiced. I was able to get my right leg up over the couch calf support and part way across prior to actually getting the upper torso in. The left leg went in with very little difficulty… I think I had a little trouble getting my left arm in, and I’m not quite sure why. I think it’s mainly because I tried to wait too long before putting my left arm in. Outside of that, getting into the capsule and the couch went just about on schedule, and we picked up the count

|

A grinning John Glenn welcomes Shepard to the White Room. (Photo: NASA) |

|

Shepard offers a last thank-you to Gus Grissom. (Photo: NASA) |

for the hooking up of the face plate seal, for the hooking up of the biomed connector, communications, and placing of the lip mic[rophone]. Everything went normally.” [21]

Joe Schmitt had one final role to play during Shepard’s insertion into Freedom 7, and it all went as planned. “I had been training with him for so long. I mean that’s all we had been doing…. My job was not only to suit them and take care of the suits, but also to put them in the spacecraft and hook up their communications, their hoses, and also their restraint straps.” [22]

Part of the ingress procedure required Schmitt to first remove an instrument panel, allowing Shepard enough room to slide in and nestle into his contour couch before Schmitt replaced the panel and attended to the restraint straps and his other pre-flight tasks.

After being physically connected with his capsule, Shepard noticed a stray slip of paper amongst his instruments which read, in the handwriting of John Glenn, “Ball games forbidden in this area.” He laughed at this little bit of levity and handed it out to the smiling Marine, who then set off to the Mercury Control Center.

Already strapped in position on a small ledge inside the spacecraft was something Shepard hoped he would not have to use – a parachute chest pack. It was there in the event of a serious problem with the main parachute prior to landing. If necessary, he

|

|

Shepard entering Freedom 7. (Photo: NASA) |

was to clip it on, manually operate and discard the mechanically actuated side hatch, then squeeze out of the rapidly descending capsule. But Shepard knew it would be an extremely difficult task extracting himself from the couch, opening the hatch, and scrambling out in time, so even though he took note of it in his checks, he quickly dismissed its presence and purpose from his mind. Although the bulk of the personal parachute made the interior of the capsule even more cramped than necessary, the planners nevertheless loaded it on this flight and the subsequent MR-4 mission.

“The preparations of the capsule and its interior were indeed excellent,” Shepard would observe in the MR-3 post-launch report. “Switch positions were completely in keeping with the gantry check lists. The gantry crew had prepared the suit circuit purge properly. Everything was ready to go when I arrived, so, as will be noted elsewhere, there was no time lost in the insertion. Insertion was started as before.

“After suit purge, the suit-pressure check showed no gross leaks; the suit circuit was determined to be intact, and we proceeded with the final inspection of the capsule interior and the removal of the safety pins. I must admit that it was indeed a moving moment to have the individuals with whom I’ve been working so closely shake my hand and wish me bon voyage at this time.”

|

Shepard prior to hatch closure. (Photo: NASA) |

|

A final glimpse of the astronaut as the capsule’s hatch is closed. (Photo: NASA) |

At 6:10 a. m., the pad technicians began the task of installing the spacecraft hatch, which was held in place by 70 bolts. The ensuing cabin leak check was completed to everyone’s satisfaction. Shepard’s training now kicked in as he began industriously working through his checklists, ensuring once again that everything was exactly as it should be, and that all the switches were at the correct settings.

Shepard later reported, “The point at which the hatch itself was actually put on seemed to cause no concern, but it seemed to me that my metabolic rate increased slightly here. Of course, I didn’t know the quantitative analysis, but it appeared as though my heart beat quickened just a little bit as the hatch went on. I noticed that my heart beat, or pulse rate, came back to normal again shortly thereafter with the execution of normal sequences. The installation of the hatch, the cabin purge, all proceeded very well, I thought. As a matter of fact, there were very few points in the capsule count that caused me any concern.” [23]

Every so often Shepard glanced into the periscope to monitor the outside activity, and would smile to himself whenever the wide-angle-lens-distorted grinning face of Grissom filled the small screen. As the White Room crew went about their business, little did Shepard realize that he would spend the next four hours on his back in the form-fitting couch, as delay after delay threatened the increasingly irritated astronaut with yet another launch scrub.

|

A cheeky Grissom peers into the capsule’s periscope. (Photo: NASA) |

|

Physician Bill Douglas gives Shepard a final “okay” sign in front of the periscope. (Photo: NASA) |

Then the voice of CapCom Deke Slayton came through. “Jose? Do you read me, Jose?”

“I read you loud and clear, Deke,” Shepard replied.

“Don’t cry too much,” Deke said as part of the Bill Dana routine.

“All right,” came the more sober response.

At 6:34 a. m., some 24 minutes after Shepard had been sealed into Freedom 7, the enclosing service structure slowly began to roll away from the Redstone, leaving the impressive white-and-black painted rocket poised pencil-like on the launch pedestal, pointed ambitiously towards the rapidly lightening dawn sky, ready to lunge free on command.

There was now an air of hope and expectation among the delay-weary hordes of reporters and members of the public who were again on the beaches and every other vantage point, listening to bulletins on their transistor radios. They had endured three frustrating and exhausting days of storms sweeping up and down the coast, thunder and lightning, and the dispiriting announcements of continued postponements. Now, as they assembled beneath a relatively cloudless dawn sky, they began to believe that this might, finally, be the day on which Alan Shepard would make history.