A TROUBLED FLIGHT INTO SPACE

The Redstone roared into the sky on what started out as the planned trajectory, but flight telemetry indicators soon began to show problems. A faulty valve was causing the fuel pump to inject too much liquid oxygen into the engine, inducing it to deliver an excess of thrust and accelerate faster than expected. As a result, the Redstone did more than was expected of it and, by burning its fuel faster than expected, triggered a chain of events which added several miles to the intended peak altitude and tacked 130 miles on to the range. Meanwhile, Ham was calmly pulling away at the levers as he had been trained to do.

When the booster exhausted its fuel supply, the Mercury spacecraft was meant to sequentially separate and coast to a peak altitude of 115 miles before falling into the Atlantic some 298 miles downrange, where a flotilla of eight ships were waiting to retrieve it. But the anomaly had caused a “thrust decay” when the rocket’s fuel was depleted. That caused the spacecraft’s emergency escape system to trigger an abort sequence. By then, the spacecraft was traveling at around 4,000 miles an hour. The emergency escape rocket reacted as it was meant to do, hauling the spacecraft away from the booster. In doing so, it accelerated to a speed of more than 5,000 miles an hour. Ham was suddenly subjected to a gravitational force of around 17 g’s, driving him hard into his couch and making him temporarily forget his psychomotor duties. As the spacecraft finally entered a state of weightlessness a couple of small electrical jolts through the soles of his feet reminded a bewildered Ham of his responsibilities and he resumed tugging at the levers. But there were still more dangers to overcome.

|

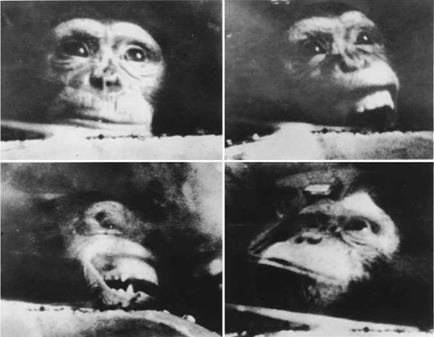

Still images from a film taken of Ham during his space flight. (Photos: NASA) |

As Flight Director Chris Kraft and his Mercury Control Center team continued to monitor the progress of MR-2, he was informed that the fuel problem and resultant over-acceleration might carry the spacecraft an extra 42 miles higher and about 124 miles further downrange, adding two more minutes of weightlessness to the mission. Of more immediate concern to Kraft was the fact that a faulty relief valve had caused the spacecraft’s pressure to suddenly drop from 5.5 to 1 psi. Fortunately, this would not affect the occupant, as Ham was sealed in a pressurized container with his own air supply. Added to this was the unhappy fact that the retro-pack had prematurely jettisoned when the spent escape tower was jettisoned. Consequently, the spacecraft would reenter excessively fast and splash down even further downrange.

William Augerson, a physician on duty in the Cape blockhouse, was monitoring Ham’s physiological progress. He reported that despite all the onboard dramas, Ham was performing his tasks just as he had been trained. Weightless for more than six minutes, he only received two small electric shocks throughout the entire journey for neglecting to push the correct levers on time. In this respect, it was an almost perfect rehearsal for a manned mission, proving that a human would easily be able to carry out maneuvering tasks even if things did not go according to plan during the flight.

As MR-2 plunged backwards toward the sea, Ham began to experience a crushing 14.7 g’s. Then, at 21,000 feet, a six-foot drogue chute automatically deployed, which in turn dragged the 63-foot main parachute from its stowage at 10,000 feet, rapidly slowing the spacecraft’s rate of descent. A search and rescue and homing (SARAH) beacon had been activated earlier, when the escape tower pulled the capsule off the spent booster. Tracking aircraft monitored this signal and steered the ships of Task Force 140 to the predicted point of impact, around 416 statute miles downrange – an error of some 127 miles.

Seventeen minutes after lifting off, the capsule smacked down hard in rough seas beyond the far end of the Atlantic Missile Range. As intended, the landing bag had deployed and this helped to minimize the shock of striking the water. Immediately after splashdown the main parachute was automatically jettisoned, fluorescent green dye was released in order to aid visual sighting, and a high-intensity light on top of the capsule began to flash.

On impact with the water, a rim of the lowered heat shield had snapped back so violently onto the hull that it breached the titanium pressure bulkhead in two places, enabling sea water to penetrate the spacecraft. A cabin relief valve had also jammed open, allowing even more water to seep in. Then, just to compound matters, the heat shield tore loose from the bottom of the landing bag and sank. MR-2 slowly began to tilt and settle ever deeper into the tumultuous seas.

Shortly after splashdown, NASA was reporting that the floating capsule would be recovered within three hours. Although telemetry indicated that Ham was alive as the capsule approached splashdown, the radio telemetry circuits were disabled on impact so no one knew how he was doing. A subsequent NASA bulletin stated, “The Mercury spacecraft in today’s test reached a velocity of more than 5,000 miles an hour, a peak altitude of about 155 statute miles, and landed some 420 statute miles downrange. Higher than normal booster thrust produced the extra velocity, altitude, and range.

The capsule has been sighted in the water by an aircraft. A recovery ship should reach the spacecraft within three hours. Telemetry received during the flight indicates the chimp performed satisfactorily.” [9]