TRAINING FOR SPACE

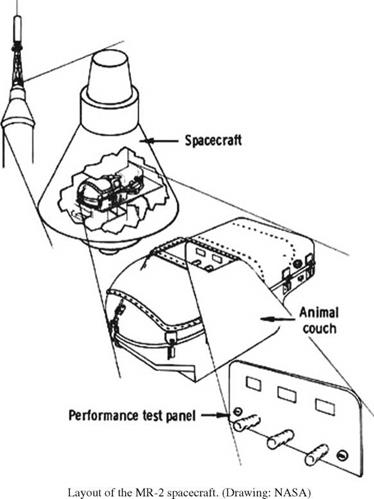

After the chimpanzees had become familiar with sitting in the steel chairs, Dittmer’s team began securing them in individually molded aluminum couches. These were smaller versions of contour couches that the astronauts would one day occupy in the Mercury spacecraft. Next, the animals were introduced to a device mounted across their lap that was called a psychomotor, a small machine specifically designed to test their reflexes and responses.

Apart from participating in tests of the spacecraft’s life support systems, one of the main tasks that the MR-2 chimpanzees had to master was pushing levers on the psychomotor in sequence throughout a brief suborbital flight, in order to prove that astronauts would be able to perform similar tasks satisfactorily.

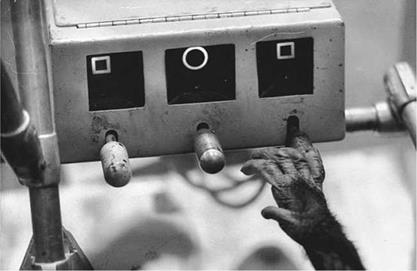

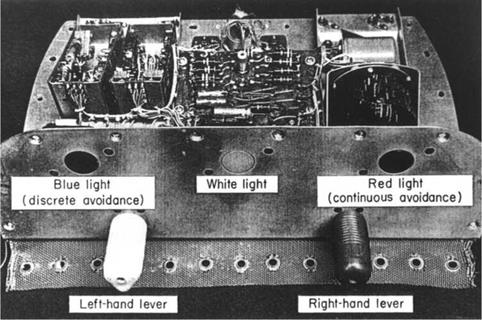

There were three lights, with three levers directly below them on the device. One light was a red “continuous avoidance” signal which glowed all the time. Another was a white light that would illuminate when the test animal pushed the lever below. If they didn’t do this every twenty seconds a mild electric shock flowed through metal plates attached to the soles of their feet. The third light was blue, and it would glow for five seconds at irregular periods every two minutes. The lever beneath this had to be pushed before the light went out or the chimp would receive a light shock. On an actual mission, this test was set up to begin at liftoff and continue through the flight, transcending periods of high g-loads and acceleration, weightlessness, and reentry.

In the post-flight Review of Biomedical Systems for MR-3 Flight, it was noted by Stanley C. White, M. D., Chief of the Life Systems Division, Richard S. Johnston, his assistant, and Gerard J. Pesman of the Crew Equipment Branch of the Life Systems Division, that the chimpanzee program was designed to parallel that of the human program.

“Its primary goal was the qualification of the man support systems,” the report said. “Through this approach, the objective of flying first unmanned, followed by an animal flight, would give the logical sequence for the qualification of the spacecraft for manned flight.

|

|

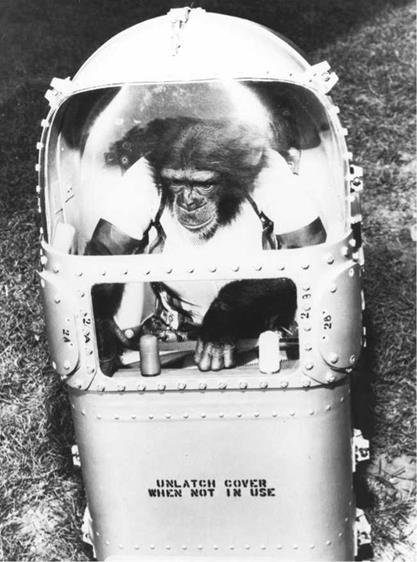

Dressed for space, Ham demonstrates to his handler that he is ready to be considered for the MR-2 mission. (Photo: NASA)

|

|

Flight training for the chimpanzees involved learning to push levers in sequence with cueing illumination. (Photo: USAF)

|

Ham, strapped into his couch and fully enclosed within his space container. Note the psychomotor panel and levers in front of him. (Photo: NASA) |

“The chimpanzees considered for the Redstone program were thoroughly trained using the calculated flight dynamics. The centrifuge and heat chambers were used. The physiological training was incorporated with the psychomotor tasks to be done by the chimpanzee during flight. It was found that early in the training program the chimpanzee would cease working during the accelerative periods, and assume his normal

|

The MR-2 psychomotor panel. (Photo: NASA) |

trained pattern promptly after the forces were released. However, subsequent training indicated that the chimpanzee could accept these new stresses and continue performance at a high level through all normal stress loads.” [5]

Throughout the chimpanzees’ training, a corps of veterinarians closely monitored their health and well-being, tracking their skeletal development with periodic exams and X-rays, as well as ensuring that they were free of any parasites. The animals also received regular checkups of their heart and muscular reflexes. Diet and dietary supplements were an important aspect of these tests, so the animals were fed small doses of antibiotics stirred into their favorite treat – liquid raspberry gelatin. In fact some of the primates enjoyed the diet and attention so much that they began to pack on excess weight, eventually washing them out of the program when they exceeded the specified limit of fifty pounds.

Even though Ham/Subject 65 trained well and was fast becoming one of the top candidates for the MR-2 shot, there were many physical, stress and readiness factors involved in the final selection – which was to be made on the eve of the mission. In preparation for MR-2, six of the most promising candidates along with 20 Holloman scientists and technical personnel were flown to Cape Canaveral on 2 January 1961 in order to acclimatize the chimps to a change in environment and to undergo final preparation for the flight, scheduled for the end of that month. Here they would be given 29 days of intense training under the supervision of Maj. Dan Mosely, DVM, in charge of Holloman’s vast Aeronautical Branch.

|

|

Facilities at the Cape for quartering, training, and preparing the six chimpanzees consisted of seven specially designed trailers in a fenced-off enclosure adjacent to Hangar S, in which the astronauts’ quarters were situated. To prevent any possible spread of disease amongst the animals they were isolated in separate cages. One of the trailers was a combined clinical and surgical facility for physical examinations, clinical laboratory analysis, minor surgery, and treatment of illness or injury. It was also used for the installation of biosensors, donning the restraint garment, and the placement of each chimpanzee in its personalized couch.

According to a report on MR-2 operations compiled post-flight by Capt. Norman Stringely and Maj. Mosely of the Air Force, and Charles Wheelwright from NASA,

|

A helmeted Ham in the lower section of his couch container. (Photo: NASA) |

“Five practice countdowns were conducted by the medical preparation team for the MR-2 flight. They consisted of preparing the subject and couch, and proceeding up the gantry. The couch was either placed outside or inserted into the spacecraft and connected to the spacecraft environmental control system and electrical system. One countdown was for a telemetry check, one for a spacecraft-pressure check, one for a radio-frequency compatibility test, and two were simulated flights.” [6]