HANDING OVER TO NASA

The Redstone’s association with Project Mercury began as the result of a January 1958 meeting of top military personnel at the ABMA. The Department of the Army had proposed a joint Army, Navy, and Air Force program to send a man into space and back, under the project working title of “Man Very High.” In April, however, the Air Force decided that it did not wish to participate, and the Navy was becoming increasingly lukewarm on the joint service venture. As a result, the Army decided to push on with the project alone. Now redesignated “Project Adam,” a formal proposal for the military space venture was submitted to the Office of the Chief of Research and Development on 17 April 1958.

As outlined in the proposal, the intention of Project Adam was to send a man on a ballistic flight to an altitude of around 170 to 200 miles in a recoverable capsule atop a Redstone missile. It was pointed out that much of the supporting research for such a space venture had already been carried out at the ABMA in Huntsville. In turn, the Secretary of the Army, Wilber M. Brucker, forwarded the Project Adam proposal to the Department of Defense’s recently created Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) the following month, along with a recommendation that the agency consider funding the project. But this was rejected in a memorandum to the Secretary of the Army dated 11 July 1958, in which Roy W. Johnson, the first director of the ARPA, indicated that Project Adam was not considered integral to the agency’s own man-in-space program.

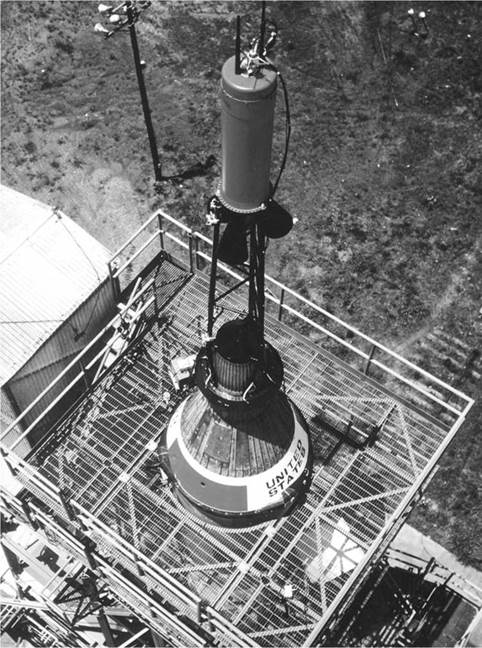

|

A Redstone missile on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral, 16 May 1958. (Photo: NASA) |

On 8 August 1958 President Eisenhower appointed 52-year-old Dr. Thomas Keith Glennan, president of the Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland, Ohio, to serve as the first administrator of NASA. For continuity his deputy would be 60-year-old Hugh L. Dryden, who had been in charge of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). NASA came into official existence on 1 October. Just two weeks later, Glennan was in conflict with the Secretary of the Army about a proposal that the Army transfer to NASA the 2,100 scientists and engineers at the ABMA and all of its facilities and personnel at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. In the end, on 3 December, President Eisenhower ordered a compromise which involved transferring JPL to NASA, but under the direction of the California Institute of Technology. The president allowed the Army to retain its ABMA and the people under von Braun, but granted NASA the right to make use of the Huntsville capabilities on a fully cooperative basis. Glennan later announced that an increasing proportion of the work undertaken at Huntsville would be shifted to his agency in future contracts.

When NASA subsequently sought discussions on the possible use of the Army’s Redstone or Jupiter rockets in support of the civilian manned space program, the Army, now without a manned space program due to the decision to abandon Project Adam, decided to cooperate. As a result, NASA issued a request to the ABMA for eight Redstone missiles to be used by Project Mercury. By arrangement with NASA, these rockets were to be assembled by the Chrysler Corporation and shipped to the Redstone Arsenal for final checkout by the ABMA.

At the time of the Redstone’s selection for the Mercury program in January 1959, there were two very different versions of the rocket. The first, designated Block II, was an advanced version of the tactical missile design incorporating an improved engine, the Rocketdyne A-7, which used a combination of alcohol and liquid oxygen (LOX) as its propellants. However, there were concerns that this propellant mixture would almost – but not entirely – achieve the thrust necessary to boost a one-ton spacecraft into space. North American Aviation set its Rocketdyne Division the task of increasing the thrust by about 5 percent with the proviso that there could not be any changes to the existing propellant systems. They finally came up with a toxic mixture of unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine and diethylenetriamine, to which the military gave the name Hydyne. When combined with LOX, this would provide the required additional thrust. The Hydyne/LOX propellant was successfully utilized by the second modified version of the Redstone. Designated the Jupiter-C, this was a multistage rocket with larger tanks and Rocketdyne’s A-5 engine. It was a four-stage version of the Jupiter-C with small solid-fuel rockets for the upper stages that placed America’s first satellite, Explorer 1, into orbit around the Earth on 31 January 1958.

On 1 July 1960, a section of the Redstone Arsenal was transferred to NASA and a few weeks later President Eisenhower and NASA Administrator Glennan attended the rededication ceremony that made it the George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, which rapidly became known by the acronym MSFC. It was here that a number of Redstone rockets would be produced and tested for the civilian space agency by the Development Operations Division of the ABMA in collaboration with the project management of the Space Task Group (STG). Cooperative panels were established between Marshall, the STG, and the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation of St. Louis,

|

The seven Mercury astronauts visit the Fabrication Laboratory of the Development Operations Division at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (which was renamed the Marshall Space Flight Center) in Huntsville. From left: Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, John Glenn, Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, Deke Slayton, and Dr. Wernher von Braun. (Photo: NASA, MFSC) |

Missouri, which was manufacturing the Mercury spacecraft, in order to implement standards, to coordinate design and operational goals between the three agencies, and to seamlessly integrate any changes into the overall program.

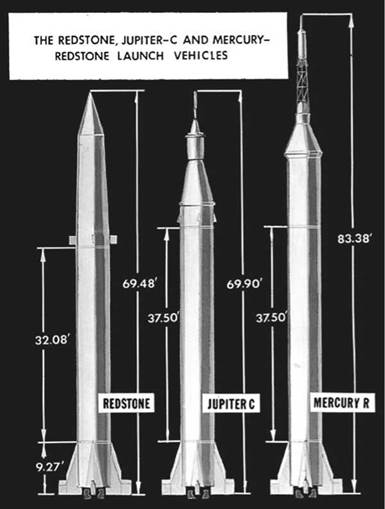

The Redstone configuration selected to meet the performance requirements of the Mercury program coupled the A-7 engine and propellants of the Block II model with the enlarged tankage of the Jupiter-C. In order to support the objectives of Project Mercury, some 800 modifications were made to the rocket’s existing characteristics and performance. This included the elongation of the 70-inch diameter tank unit by six feet to hold the fuel required for an additional 20 seconds of engine burn time. A new instrument compartment and adapter section was manufactured to mate with the spacecraft, along with an abort system developed by MSFC to protect the capsule and, eventually, its human occupant. With the capsule and escape power mounted on top, the Mercury-modified Redstone now stood at an overall length of 83 feet. The total liftoff weight at launch would be 66,000 pounds.

|

|

A close view of the test capsule and escape system. (Photo: NASA/MSFC) |

Dr. Joachim Kuttner was one of Wernher von Braun’s team of German scientists, and he said at the time that a great deal of care was taken in the production of each Redstone booster. “As these thin sheets of aluminum are curved and welded, each seam is minutely inspected by X-ray to make sure there are no invisible flaws that might give way under the extreme stresses of flight. Every component we use bears a special seal representing the winged god Mercury. This symbol constantly reminds assembly-line workers that a man’s life depends on the product.” [4]

|

A comparative illustration of the Redstone, Jupiter-C, and Mercury-Redstone launch vehicles. (Photo: NASA, MSFC) |