The “Reptile Aeronautical Press”

Two related complaints came together in the arguments that were mobilized on behalf of the “practical man.” First, it was said that the designers of airplanes did not need mathematical knowledge and that persons who did possess such knowledge were mere theorists who were ill equipped to deal with real problems. The National Physical Laboratory, it was said, was staffed by mathematicians and theorists rather than engineers with practical experience. Second, those who were in the employ of the government led cushioned and subsidized lives that protected them from the bracing rigors of the market. This complaint included the staff at the NPL but was particularly directed at the Royal Aircraft Factory.

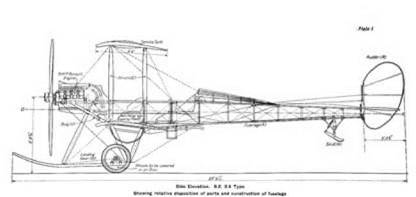

Within a year of the ACA’s founding, the aeronautical press was asking for evidence that the committee’s work was bearing fruit. The anonymous writer of an editorial in Aeronautics in 1910 lamented that “it is too late to renew criticism of the composition of the Committee or of the limitations placed on its work; it will be sufficient once again to place on record our opinion that in both respects the Committee is bound largely to be a failure so far as results of immediate practical value are concerned.”57 In an article on aeronautical research in the Aeroplane of August 31, 1911, P. K. Turner, a regular contributor, said it was time that theory and practice were brought together. Was this not why institutions such as the National Physical Laboratory had been set up? “But it appears that the workers at these institutions, like the monks of old, are growing fat and useless; and of all the shameful wastes perpetuated in our alleged civilisation, the worst, in my eyes, is an equipped factory, laboratory, or office, where owing to the incompetence of those in charge or the laziness of their subordinates or both, or vice versa, nothing is done.”58 The issues came to a head at the military air trials of 1912 held on Salisbury Plain. Private contractors, British and foreign, were invited to enter their aircraft into a competition to see which ones best met the performance criteria laid down by the military. The competition was organized by O’Gorman, though the terms of the competition precluded the government Factory from formally entering its own designs. Although not an official competitor, a Factory model, a tractor biplane called the BE2, was put through its paces during the trials and informally faced the same tests as the others. The designation BE came from a system of classification developed by O’Gorman. The E stood for “experimental”; the B for “Bleriot-type” and referred to the position of the engine at the front of the aircraft. Pusher aircraft with the engine behind the pilot were given the designation F after the pioneer Henri Farnam. The BE2 was designed by Geoffrey de Havilland, who had been taken onto the staff of the Factory after successfully building some aircraft of his own. The BE2’s performance manifestly outclassed that of the entries from private firms. It was reasonably stable, made good speed, and de Havilland even set a new altitude record with the BE2 during the trials. The official winner was a machine entered by Cody, but the War Office proceeded to ignore the competition and focused its interest on the superior machine, even though it had been precluded from official entry. It offered contracts to private constructors to build not their own machines, but twelve of the government-designed BE2s. In an improved form this machine became, for a number of years, the mainstay of the Royal Flying Corps. Figure 1.4 shows a side elevation of the BE2A.

For the government’s critics the policy of contracting out government designs constituted an outrage. It was denounced as an attack on private enterprise that strangled all design initiative.59 But private enterprise had put up a miserable showing at the air trials. As one eyewitness noted: “Of the seventeen British aeroplanes that were nominally in evidence, at least seven of the newer

|

figure 1.4. The BE2 was developed by the Royal Aircraft Factory and played a central but controversial role in the British war effort. The highly stable BE2 has been called one of the most interesting airplanes ever built. This side elevation is from Cowley and Levy 1918. |

makes were either unfinished or untested on the opening day, and thus some of the very firms for whose benefit the trials had, in a measure, been organized, spoiled their own chances in competition with the older constructors who, for the most part, had entered well-tried models.”60 An editorial in the Aero for September 1912 admitted: “It is undoubtedly a fact that the majority of our home manufacturers have not gained in reputation through participating in the military trials.”61 The same point was conceded by an editorial in Flight in which it was acknowledged that the BE2 was “one of the best flyers ever produced.” Of the firms that were granted a contract to produce the BE2, the editorial continued, “not everyone could have as readily justified a similar demand for its own machines on demonstrated merits in the Military trials.”62 The War Office decision was reasonable; if anything it was more accommodating of the sensibilities of the private manufacturers than it should have been. Looking back from 1917, an editorial in the journal Aeronautics acknowledged that “before the War there was in the whole country not a single decently organised aircraft manufacturing firm.”63 For example, the Handley Page Company had accepted orders to produce five of the twelve BE2s, but it failed to deliver even this small number. Only three of the machines had been delivered by 1914.64 If the editorial in Aeronautics is to be believed, the situation at Handley Page was the rule rather than the exception; not a single manufacturer of the BE2s made its delivery on time. The editorial went on: “We are not blind to the faults of the Royal Aircraft Factory, which are of a nature which seems inseparable from any state-owned institution. Nor do we ignore the fact that the Factory was bitterly detested and thoroughly distrusted by the industry at large. But truth compels us to recognise the fact that the industry was chiefly responsible for its own grievances” (185). The writer of this passage was probably J. H. Ledeboer, the editor of Aeronautics. The self-critical tone was hardly typical of most of the polemics unleashed against the Royal Aircraft Factory, though the assumption that government institutions would be inferior to those of the business world certainly was.

In Parliament the aircraft manufacturers had the support of, among others, William Joynson-Hicks and Arthur Hamilton Lee, both Conservative MPs, and Noel Pemberton Billing, an independent MP and founder of the Supermarine company. Billing had conducted his theatrical campaign for election on the basis of his commitment to, and knowledge of, aviation and all matters relating to it. The various critics of the government did not always agree with one another, but their combined voice was loud and persistent. Week after week, and year after year in the pages of the aeronautical journals, in Parliament, and in the right-wing press, they directed their anger and contempt at the Advisory Committee, the National Physical Laboratory, and the

Royal Aircraft Factory. Every setback, every accident, every tragedy was used as a stick with which to beat the government and as proof of the inferiority of government design and construction compared with private enterprise.

The BE2, and everyone associated with it, became the objects of a campaign of denigration. As so often happened in the early years of aviation, accidents occurred, and a number of persons flying the BE2 were tragically killed. One was Lt. Desmond Arthur, whose BE2 broke up in the air at Montrose at 7:30 a. m. on May 27, 1913. Lt. Arthur was a friend of C. G. Grey, the editor of the Aeroplane, and the loss fed Grey’s state of permanent anger against the government.65 Another victim was E. T. “Teddy” Busk, a brilliant engineering graduate from Cambridge who had joined the Royal Aircraft Factory in the summer of 1912. Busk had been conducting a program of experiments designed to improve the stability of the BE2 when the machine he was piloting caught fire.66 This accident, and the other fatalities, provided the critics with the excuse for which they were looking. “The Victims of Science” was the headline in the Aeroplane of March 19, 1914.67 Grey (see fig. 1.5) exploited the opportunity to the full. He argued that it was the scientific approach to airplane design that had killed these unfortunate men. He wrote: “I submit

|

figure 1.5. C. G. Grey, editor of the Aeroplane and vehement critic of the Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. (By permission of the Royal Aeronautical Society Library) |

that if the Department of Military Aeronautics will hold an enquiry into the design and construction of Mark BE2 biplanes and will take the evidence of workshop foreman and practical constructors—apart from the scientists and theoreticians—among contractors who are building the BEs they will obtain sufficient criticism to condemn almost every distinctive feature of the BE— provided always they can guarantee that in the event of the practical men speaking their minds they will not jeopardise their firm’s chances of obtaining further orders” (320).

Grey was an accomplished polemicist and he took care to cover himself lest the criticisms he was confidently predicting were not forthcoming. He implied that this could only mean that sinister, government forces were suppressing them. Having secured his line of retreat, Grey then asserted that the deaths had been caused by criminal negligence and he knew who the criminals were: “Those responsible are the people, if you please, who have ‘the best brains in the world,’ and through whom aeroplane design is to excel. These are the people who base their calculations on the theories of the armchair airmen of the National Physical Laboratory” (321). When the Aeronautical Society opened a subscription to honor Busk, Grey accused it of exploiting the young man’s death. He had an unpleasant talent for criticizing others for what he was doing himself.68

Political attacks on the aeronautical establishment became even more intense after the start of the war in 1914. The summer of 1915 saw the Fokker Scourge. Anthony Fokker, a Dutch designer working for the Germans, had developed a forward-firing machine gun, synchronized to fire through the propeller disc. He fitted it to an otherwise undistinguished monoplane, and the new arrangement marked the emergence of the specialized “fighter aircraft.” It gave the Germans a marked advantage and, for a while, increased the losses of British pilots and machines. The BE2, whose stability compromised its maneuverability, was no match for the Fokker Eindecker—not, at least, when the Fokker was flown by the particularly skilled pilots to whom it was selectively assigned. By any standards this issue was one of importance for a country at war. Rhetorically, however, it became another opportunity to voice the interests of the aircraft manufacturers. In the House of Commons, Pemberton Billing denounced the government and military authorities as “murderers.” His claim was that if the young men of the Royal Flying Corps had been given machines designed and built by private firms rather than government agencies, they would be alive today.

It would be a study in its own right to trace all the twists and turns of the protracted, political campaign conducted by Billing, Grey, and the manufacturers, and it would be no easy matter to decide, in every case, which complaints had substance and which were unscrupulous exaggerations and self-serving falsehoods. Given the seriousness of Billing’s allegations, and the place in which they were made, it was inevitable that official inquiries had to be launched. Two issues had to be unraveled: (1) was the Royal Flying Corps conducting its military business properly? and (2) was the Royal Aircraft Factory dealing improperly with the private manufacturers? The Burbridge Committee addressed the first problem and the Bailhache Committee the second. During the course of these inquiries, Pemberton Billing’s behavior became so eccentric and evasive that even former supporters began to back away. Flight, which had previously welcomed his election, decided that the talk of the “deadly Fokker” was a gross exaggeration and suggested that there must be some ulterior motive.69 Soon the editorials were dismissing his indictments as “irresponsible” and “sensational” rather than “the measured views of a man in earnest for the welfare of his country.”70

The official inquiries could find no basis in fact for Pemberton Billing’s accusations against the Royal Flying Corps, but he and the other critics effectively “won” the argument against the Royal Aircraft Factory.71 The report conceded that there had been inefficiencies. The tepid defense of the Factory meant that the interests represented by the critics ultimately prevailed.72 Flight, which had frequently been supportive of the Advisory Committee, the National Physical Laboratory, and the Factory, now concluded that the rights of the manufacturers had indeed been encroached upon.73 The editorial column proudly affirmed the principle that private enterprise was always superior to government, and then promptly asked for government subsidy for the aircraft industry.74 The government acceded to the critical pressure of the manufacturers and the Aircraft Factory was turned exclusively toward research rather than design. O’Gorman was removed, and his team of designers and engineers dispersed into the private sector. An impartial assessment of the rights and wrongs of the issue would, however, have to note that, before the restriction on its activities, the personnel of the Royal Aircraft Factory had produced one of the most outstanding fighter aircraft of the war, Henry Folland’s SE5. (In O’Gorman’s nomenclature the S stood for “scout” and the E for “experimental.”) Folland and his colleagues had skillfully balanced the competing demands of stability and maneuverability to produce one of the most formidable fighting machines of the war and an aircraft that was a match for anything its pilots might meet.75

The critics also “won” in that, by 1915, they had managed to hound Haldane out of office.76 Haldane was denounced in the right-wing press as a proGerman sympathizer. He was said to have opposed and delayed the dispatch of the British Expeditionary Force to France in 1914 and to have known of the

German war plans without informing his Cabinet colleagues. There was not a shred of truth in any of these allegations. Indeed, it was only thanks to Haldane’s earlier army reforms that the country had a viable expeditionary force at all. The charges even alluded to a secret wife in Germany and to Haldane being an illegitimate half brother of the kaiser. It was ludicrous and vile but it worked, and the “reptile aeronautical press,” as O’Gorman justifiably called it, played its part in the affair with enthusiasm.77 The episode must count as one of the most disreputable in twentieth-century British politics.78

During the Great War enormous social pressure was placed on men to contribute to the war effort and not to shirk their patriotic duty to lay down their lives on the field of battle. Pacifists and critics of the war were reviled. This practice was routine in the aeronautical press.79 Grey was happy to mobilize the hatred of “trench-dodgers” and use it against those who, instead of being at the front, were working at Farnborough and Teddington. He reprinted an article from the Times (under the title “The Farnborough ‘Funk-Hole’”) asking why the fit young men seen coming in and out of the Aircraft Factory were not in France.80 The theme was taken up again when reviewing the Advisory Committee’s report for 1917. As usual, said Grey, the report is devoted to the glorification of the National Physical Laboratory, though he noted with approval that two “practical men of proven merit” had been brought on to the Engine Sub-Committee and the Light Alloys Sub-Committee.81 He was, however, censorious of those who were performing basic, hydrodynamic experiments, for example, those involving water tanks. Making play with the word “tank,” Grey declared that “if some of these able-bodied young men were to take a course of experimental work in motor-tanks at the front they would confer greater benefits on their native land” (315). Meanwhile Grey was corresponding with Winston Churchill to plead for his own exemption from the inconvenience of wartime obligations. Judging from surviving letters, now in the archives of the Royal Aeronautical Society, Churchill, though brief and formal in his responses, duly obliged, and through his intervention Grey got the exemptions for which he had asked.82 Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.