The Structure of the Committee

The administrative structure that crystallized in Haldane’s mind was for a committee of ten or eleven, involving persons of the highest scientific talent, to address technical problems presented to them by the Admiralty and War Office. Unlike the proposed committee itself, these two old-established bodies would be responsible for commissioning and even constructing military airships and aircraft. The committee would analyze and define the scientific and technical problems encountered by these constructive branches of the military and would pass them on to the National Physical Laboratory (the NPL). The laboratory, which was based at Teddington just outside London, was to have a new department specializing in aeronautical experiments. This department would produce the answers to the questions posed by the Advisory Committee. Financially, the committee would be accountable not to the War Office or Admiralty but to the Treasury.

The structure that emerged conformed to this plan except for the addition of one more unit. In 1911 the former Balloon Factory at Farnborough, belonging to the army and the home of Dunne and his supporters, was turned into the Aircraft Factory and then (in 1912) into the Royal Aircraft Factory (the RAF).27 After the Dunne episode it had been decided to drop aircraft research at Farnborough, but this resolution was now rescinded. It was thus determined, after some indecision on Haldane’s part, that new aircraft were to be designed by the government itself and built at its behest by private manufacturers.28

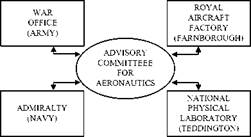

An organizational chart of Haldane’s arrangement would therefore take the form shown in figure 1.2. Problems passed from left to right on the chart,

|

figure 1.2. The Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and its institutional context. The Advisory Committee was founded in 1909 and reported directly to the prime minister. |

from the Admiralty and War Office through the ACA to the National Physical Laboratory and the Royal Aircraft Factory. After experiments and tests had been completed, according to a schedule agreed on with the ACA, information and answers were passed back, from right to left on the chart, in the form of confidential technical reports. After these were discussed and agreed on by the ACA, and any required amendments had been made, the outcome was to be published in the form of a numbered series called Reports and Memoranda—a series that, over the years, ran into thousands and was to become famous for its depth and scientific authority. Each year the Advisory Committee presented an annual report containing an overview of its activities to which was attached, as a technical appendix, a selection of the more important Memoranda.

With the passage of time, and the increased workload imposed on the ACA, the original committee was broken down into a number of subcommittees to which further experts were recruited from the universities, Farn – borough, and Teddington. Thus there was an Aerodynamics Sub-Committee, an Accidents Sub-Committee, an Engine Sub-Committee, a Meteorological Sub-Committee, and so on. Sometimes the subcommittees were further broken down into panels, such as the Fluid Motion Panel, which was part of the Aerodynamics Sub-Committee. Such a structure may seem complicated and bureaucratic, but viewed with the benefit of hindsight, it proved highly effective.