The Final Account

At the latest by the summer of 1944 the realists at OKL must have admitted, at least to themselves, that – failing a miracle – the defence of the Reich was entering its final stage. Only by significantly increasing the percentage of enemy bombers shot down was there a possibility of retrieving the situation.

The quality of the Reich (non-flak) air defence was governed by three factors: pilots, aircraft and fuel. A shortage of pilots meant a reduction in the number of machines aloft, but a shortage of fuel meant closing the book no matter how fanatical the pilots or advanced the aircraft. There were other lesser factors, but they all added up to the same thing. Everyone involved in air defence, from

u

Goring to the youngest Flieger, had to doubt victory. After several years of a war of attrition, the Allies were no longer faced by the invincible Luftwaffe of 1940. With the exception of the Fw 190 D-9, D-ll to D-13 and above ah the Та 152 H-l, most of the piston-engined aircraft were no longer the worry they had once been for Allied escort fighters and bombers. The Luftwaffe workhorses, the Bf 109 G-6, G-14 and K-4 were still good, but not superior.

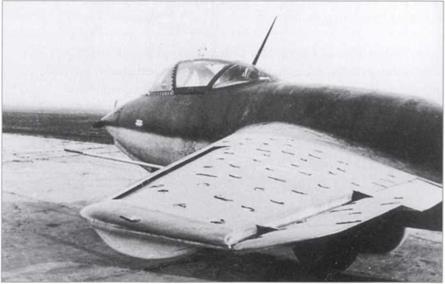

The enormous, ever-present Allied air armadas dominated the skies over the Reich. From the end of 1944 they roamed where they wanted, reducing refinery after refinery, aircraft factory after aircraft factory, town after town to ash and rubble. They cut transport routes and thus the supplies of new material to the front, slowly but surely bringing air defences to a stop. Once the Reich railway network was ruined, the beginning of the end was reached. From 1944 there was only one slight hope, and this was the construction of the greatest number of jet fighters possible. By means of Me 262 A-la fighters, relatively cosdy to produce, Allied mastery of the air might perhaps begin to fall away by the summer of 1944. Yet the small production runs of these aircraft resulted initially in relatively few operational units, such as JG 7, receiving the new fighter. Sorties by groups of 30 or more machines therefore remained the exception to the very end. Sections of OKL pinned their hopes on the He 162 Volksjager to turn the tide at the last minute. Using thousands of these small jet fighters, taking off with rocket assists from virtually anywhere, the Luftwaffe could have wounded Allied air supremacy fatally within months. That was the plan, but plans change and He 162 production was overshadowed by the Me 262. Thousands of machines planned by the Riistungsstab were cancelled.

Of greater concern was the supply of fuel for impending operations. The shortage caused a fall in fighter operations from month to month. Attacks on Allied operations towards the war’s end, for example by night fighters, were only possible using veterans and aces, for inexperienced pilots could never have found their way through the defence. The day fighters received the last of the fuel. Since the refineries were wrecked and no more benzine was forthcoming, resort was had to the last reserves. Finally a mix of various grades of benzine was supplied for the most urgent flights. Some J-2 fuel was available for most jet flights, although the modest quantities allowed no operations on a large scale.

New personnel arriving at the fighter units did not have the lengthy training period of former days behind them, and from 1944 they were cannon fodder. The leadership was keener than hitherto on a fanatical commitment to destroying that ‘special target’. Youths, completely without combat experience and ignorant of tactics, were to spring into the breach. They would man new aircraft such as the Natter or Volksjager for what amounted to little more than kamikaze missions. With rocket-driven ‘midget fighters’ and ‘local installation protectors’, OKL would make a final attempt to guard core areas of armaments

production, above all the fuel industry. But for that, most aircraft were not in the least suitable.

The suicide pilot ushered in a new phase of total war. Veteran, highly decorated men and also raw beginners were to ram their opponents if all else failed during the attack. Operation Elbe was the prime example. German losses were so high that it could not be termed a success despite the toll in enemy aircraft, and the bulk of successes were achieved by veteran pilots in piston – engined fighters and the jet escort.

Even the more senior operational pilots who flew in the last days rarely landed undamaged once enemy fighters had learned to patrol the home airfields waiting to pick off the soft target presented by a landing Me 262. The consequences of too short a period of initial training, or jet-conversion training, often made themselves felt. Most had to make do with a few minutes’ conversion flying in the Me 262 or He 162 for lack of aviation fuel. Learning to handle the new turbines outweighed the basic techniques, which had to be assimilated during operations.

Realists within the General Staff and OKL felt at the beginning of 1945 that the prospects for victory had receded into the far distance, and the main job now

was to bring as many civilians as possible to central Germany from the east and so protect them against the Red Army. Fighting on was the means to that end. That it would not be easy to slow down the advance of enemy ground forces was clear to all. Because of its lack of bombers, the Luftwaffe could promise no miracles. In the spring of 1945 only a few pilots could be sent even on such important missions as destroying major bridges since the necessary aircraft simply did not exist.

Ground successes were achieved mainly by Fw 190 F-8s in the Jabo role and Me 262 Blitzbombers in the face of too little fuel and too few airworthy machines. Sufficient pilots were available, but against massed Soviet tank armies with thousands of T-34s and Stalins, mere Staffeln of aircraft were not enough even when armed with the recendy introduced Panzerblitz or Panzerschreck rockets. Although during the closing phase of the war countless Soviet tanks were destroyed, it hardly changed the overall picture. Now a new dimension became unmistakable, but the ‘total mission would do little more than win the pilot a posthumous decoration or promotion. Operations such as Freiheit, the sacrificial attack on the Oder bridges, or Bienenstock, the small Panzerfaust-armed training machines, were hopeless from the outset, as were the Mistel attacks. Because of tactical problems, particularly the lack of air superiority in the battle area, not to mention the immense groups of Soviet flak batteries, these special aircraft did not obtain the successes predicted of them, and neither did the Hs 293 and other ‘wonder’ weapons.

Despite all setbacks and doubts there persisted through the last six months of World War II an underswell of hope for, or rather a vague belief in, Endsieg – ‘Final Victory’. It received new impetus once the Waffen-SS began to involve itself increasingly in air armaments. Thanks to its vast army of slaves, the SS was a power to be reckoned with. After it had begun to complete the underground factories, it moved in step by step to take over the rocket projects, while SS – Obergruppenfuhrer Jiittner proposed to enlarge the trawl to cover general aircraft production as well. The main aim of the SS, the last trump, was to get the remote – guided ground-to-air flak rocket operational. The necessary technology was not advanced sufficiendy, however, and at the end of 1944 industry was still not in a position to develop and mass-produce reliable systems, while Allied air raids brought the manufacture of synthetic fuels to a standstill. By March 1945 it was clear that the necessary fuels for flak rockets could not be made available in sufficient quantity, and this applied also to high-value materials needed especially for engines and electronic control equipment.

What remained was basically a belief in a miracle, for the desperate situation in which the German Reich now found itself could not be saved by Plenipotentiary Kammler. All his efforts were in vain, especially his pressure to have built the supersonic flying-wing fighter designed by the Horten brothers

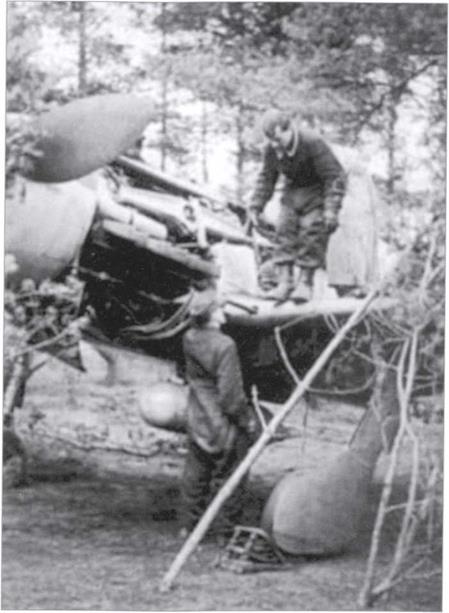

towards the end, and for which capacity was lacking. Allied forces broke through to the heart of Germany too rapidly, and industry had no further chance to realise its ambitious plans. At the end, its futuristic prototypes littered the boundaries of airfields, half complete and draped in camouflage netting, awaiting discovery by the victors. For them these would be interesting finds, although the files with the mathematical data were of much higher value.

After traditional machines failed the Germans, mainly for lack of fuel, there was nothing left except the weapons of mass destruction. The miracle explosive never appeared, and neither did the chemical and nerve gases which Hitler refused to countenance. Thus the Luftwaffe leaders were reduced to planning for the eventuality that for some inexplicable reason the Allied advance might grind to a halt until the autumn of 1945, allowing some of the new weapons below ground to become ready, particularly new jet fighters and synthetic fuel. This would have allowed the war to proceed for a while. The Allies did not oblige, however, and seized all the plans for themselves.