ffensive operations were naturally to the forefront in Luftwaffe tactical thinking. In view of the enemy superiority piston-engined aircraft such as the Ju 87 and Fw 190 were ever less suitable to relieve pressure on German troops and to strike hard at the enemy. Knowing this Hider had decided that he needed aircraft able to combat a numerically superior enemy in the case of invasion. The solution appeared to him to be the Blitzbomber. These would be machines such as the Ar 234 or Me 262 which, by virtue of their great speed, would be able to operate even over regions where the enemy had aerial superiority. Because these machines were not available until the summer of 1944, and far too few Blitzbombers were on hand, their pilots’ tactical successes were modest.

Fighter Bombers

The need to engage Soviet tank groups assumed particular importance from mid-1944 once the Red Army had begun to undermine the foundations of the Eastern Front, and not only Army Group Centre was staring at disaster. An even greater material superiority was making its presence felt on the Western Front.

Despite the comparatively high achievements of the single-seater Fw 190, in the final phase of the war attacks at dusk or in the early morning were more numerous than in broad daylight and were confined mainly to areas with poor AA defences or few enemy fighters. The Fw 190 was still a very dangerous opponent in skilled hands. Its fixed weapons were normally two MG 131s built into the fuselage, and two MG 151/20s in the wing roots. Pilots would sometimes unship some of the guns to save weight.

Fw 190s would often attack the more rewarding targets in a restricted area in a ‘rolling attack’. As in anti-tank operations some of the attacking machines would tie down the enemy defences by dropping anti-personnel bombs from disposable containers. This could be either an ETC 501, 502 or 503 bomb container below the fuselage and four ETC 50s or ETC 71s below the wings. These made it possible to use all standard types of bomb. Used with small HE or hollow-charge bombs they could be extremely destructive against enemy

vehicles, whether stationary or mobile. The potential was obviously greater the larger the formation. Occasionally all machines of a Gruppe would be involved, but when few aircraft were operational a number would fly nuisance raids and perform reconnaissance or weather-reporting duty on subsequent flights.

At the beginning of 1945, SG 4 succeeded in assembling over 100 Fw 190 F-8s to hold back the Allied advance using low-level techniques. Many were lost during the flight to the target while air raids on airfields in western Germany also caused losses. Most Fw 190 fighter-bombers were grouped in three Geschwader, SG 1, SG 4 and SG 10. SG 1 had up to 115 machines; at the beginning of the year SG 10 had over 70. Major Jabo operations were carried out as a massed unit, in formation for the outward and return flights but with individual attacks.

On 10 January 1945, only SG 4, consisting of the Geschwaderstab and I. to III. Gruppen flying Fw 190s, and the night-attack Gruppen NSGr 1,2 and 20 were attached to Luftflotte Reich. Far more low-level units were distributed along the Eastern Front. With Luftflotte 6 were III./SG 3 and NSGr 3. These were equipped with only obsolete auxiliary aircraft such as the slow Ar 60 and Go 145. SG 2 and 10, and IV./SG 9 were operational at Luftflotte 4. IV./SG 9 had more than ten machines mostly Fw 190s and Ju 87s. I. and II. Gruppen had 66 Fw 190s between them. Ju 87 Ds were still being flown by III./SG 2, while SG 10 had all Fw 190 As and Fs. On 10 January 1945 another 65 of these aircraft became available.

Luftflotte 6 provided the defensive force in the central section of the Eastern Front with three Jabo Geschwader equipped with Fw 190s. SG 1 and SG 2 had two Gruppen each, SG 77 had three relatively strong Gruppen and included the specially equipped night unit NSGr 4 with 60 Ju 87s and Si 204 Ds.

|

By the end of January 1945 Russian armies in East Prussia had occupied virtually the whole area between Konigsberg (Kaliningrad) and Lotzen (Gyzycko) and were heading north for the Frisches Haff. Graudenz (Grudziadz) and Thorn (Toruri) were encircled and Elbing (Elblag) came under threat after strong units crossed the Narev. Further attack wedges were moving simultaneously for the territories along the Warthe and in Upper Silesia. On 1 February numerous Jabo Gruppen were operating against the Soviets in the Luftflotte 6 region. SG 1 Geschwaderstab had three Fw 190 F-8s and another 104 in I. and III. Gruppen, although only half the machines were operational. SG 2 had only two Gruppen: II./SG 2 flew the Fw 190 F-8 with anti-tank rockets, III./SG 2 the Ju 87 D-5. In SG 3,4 and 77, Fw 190 F-8s were used on operations, each having a Staffel of 12 aircraft equipped with Panzerblitz or Panzerschreck rockets.

|

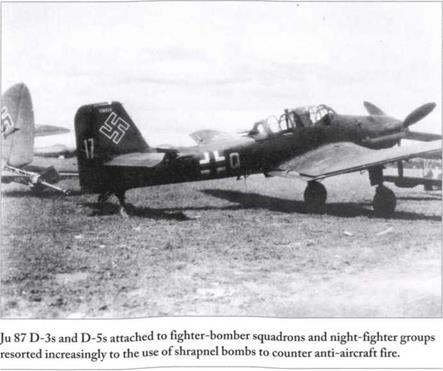

Night fighter-bomber units carried out their operations in all weathers. The poor conditions on airfields often led to crashes as with this Ju 87 D.

|

Besides the operational Geschwader there were up to six Jabo formations consisting mostly of fighter and night-fighter units. The largest were two units of JG 300 and JG 301. The first was composed of I., II. and IV./JG 300 and 3./JGr 10, which had 109 Bf 109s and 46 Fw 190s; fighter-bomber unit JG 301 was three Gruppen plus II./ZG 76. Gefechtsverband (Battle Unit) Major Enders had been drawn up from Stab, Training SG 104 and II./SG 151, while Gefechtsverband Oberstleutnant Robert Kowaleski had crews from KG 76 plus the test commando of the Air Navigation School, Straussberg. This unit had only eight Ju 188s and five He Ills, but the crews were veterans.

At the end of January, the Soviets had assembled strong forces and surrounded Posen. The final battle against hopeless odds was fought out in the city centre between 19 and 23 February. From 13 February fighting raged at Glogau/Oder, but with air support the Germans held out until 2 April. At the beginning of February the Red Army had crossed the Oder between Kiistrin (Kostrzyn) and Frankfurt at several points and established bridgeheads on the western bank. Another strongpoint was north of Fiirstenburg. The Russians had gained ground east of Stettin (Szczecin) although the German strongpoint at Altdamm held initially. At Lauban (Lubari), German Panzers won a victory at the beginning of March after wiping out large sections of 7th Guards Armoured Corps assisted by Jabos. Between 6 and 12 March, Russian divisions broke through towards Danzig and Stolpmiinde (Ustka), being held temporarily only with the greatest effort just short of their objective.

Despite all restrictions, between 1 and 31 March 1945 1. Fliegerdivision alone flew 2,190 sorties over the Eastern Front. 172 Russian tanks and more than 250 lorries were claimed destroyed, another 70 tanks damaged. Luftwaffe Staffeln shot down 110 enemy aircraft and damaged 21 others. At 4. Fliegerdivision SG 1 flew 619 missions, SG 3 66 and SG 77 123 in March 1945. Pilots of SGI dropped 295 tonnes of bombs and 36 tonnes of disposable containers of bombs, and though few tanks and lorries were destroyed at least 26 direct hits on bridge targets were claimed.

Amongst the most important units on defensive operations in April were SG 1 with over 89 Ju 87s and Fw 190s in all. 91 Fw 190 A-8s and F-8s were operational at SG 2. Stab and II./SG 3 had about 40 Fw 190 F-8s: SG 77 had 99 operational machines in its three Gruppen. An obstacle to large numbers of operations was the shortage of fuel, as so often, and a fair number of these aircraft were to be found parked on the airfield fringes at any given time.

In a successful attack by SG 1 on 11 April, 17 Fw 190 pilots dropped the usual SC 500s, plus five SC 500s with an experimental explosive filling and 16 SD 70s on railway and bridge targets near Rathstock. On 16 April two Fw 190 F-8s were lost to Russian AA fire, but the remaining pilots destroyed a number of vehicles. During these weeks Luftflotte 6 had around 250Jabos, mostly Fw 190

F-8s, and relatively few Ju 87 Ds. This force was able to call on well over 100 Bf 109s of JG 4,JG 52 and JG 77 for protection.

Meanwhile the war had moved closer to the heart of Germany as merged German divisions, Volkssturm and reserve units could do little to stop the Allied advance. On the Autobahn at Radeberg, German pilots destroyed three tanks and blocked traffic for some time. Over Cottbus-Finsterwalde-Lubben, 62 Jabos flew numerous attacks against enemy artillery and bombed an airfield occupied by the Russians.

On 24 April VIII Fliegerkorps had four Gruppen of SG 2 and SG 77 while 3. Luftwaffen-Division had additionally three Gruppen from SG 4 and SG 9 and an anti-tank Staffel. Fw 190 pilots scored noteworthy successes. Even from positions of great numerical inferiority they were able to strike hard against the Russians in ground attacks in support of Army Group Schorner.

In the last few nights of April 1945, crews of SG 1, who had been at Gatow/Mecklenburg until 26 April, sortied to relieve the pressure on Berlin. They flew as a rule twenty operations daily over the burning city. The strength of the enemy had become overwhelming: on the night of 1 May some of the 39 Fw 190 F-8s attached to III./KG 200 dropped containers of supplies to the defenders.

Despite the precarious situation, on 3 May the Luftwaffe could still call on a number of Jabo units although operations were now greatly limited by lack of fuel and bombs. Luftflotte 4, responsible for the air support of Axmy Group

|

One of the most useful German fighter-bombers at the war’s end was the Fw 190 D-9. This machine was armed in the main with anti-personnel bombs.

|

South and the Commander-in-Chief South-East, had I./SG 10 at Budweis and II./SG 10 at Weis, where the remnants of SG 9 were stationed on anti-tank duty.

I. /SG 2 pilots at Graz-Thalerhof engaged enemy forces advancing from the Alps: two more Jabo units served Seventeenth Army, these being Jabo unit Weiss with 3./NSGr 4 and II./SG 77 for night and daylight attacks respectively. Gefechts- verband Rudel, most of which was at Niemes-Sud, was composed of II./SG 2 and 10. Anti-tank Staffel. Its commander, Oberst Hans-Ulrich Rudel, had been awarded the Gold Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross on 29 December 1944.

II. /JG 6 flew fighter escort for his machines.

Luftwaffenkommando West (from 1 May 1945 Luftwaffen-Division North Alps) was made up of remnants of disbanded night-fighter units and sections from JG 27, 53 and 300, and was used increasingly at the end for low-level attacks. Although hostile operations against the Western Powers were terminated on 6 May, there was no let-up in the fight against the Russians. Strikes against their supply lines in the rear and against forward units were flown almost to the very end. When the general fuel situation at the excellent Prague aerodromes deteriorated drastically, the last aircraft there were destroyed by their pilots, although a few managed to fly out and surrender to the Americans.

Despite the successful change-over at many anti-tank Staffeln from the Ju 87 G-2 to the faster Fw 190 F-8, and the introduction of efficient rockets

such as the Panzerblitz, the collapse of the infrastructure and the lack of fuel and ammunition meant there was no possibility of holding the Western Allies at the Rhine and the Red Army at the Oder.

At times it seemed possible that Jabo jets might be the way to improve matters, but the number of available Ar 234s and Me 262s was insufficient. It is, however, worth examining the role played by these aircraft.

At times it seemed possible that Jabo jets might be the way to improve matters, but the number of available Ar 234s and Me 262s was insufficient. It is, however, worth examining the role played by these aircraft.

The Blitzbomber

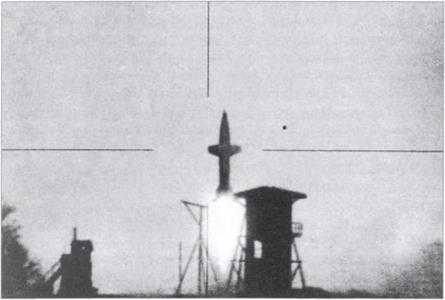

The immense numerical superiority of the enemy appeared to have only one solution, which was to equip all fighter-bomber squadrons with jets. The only bomber Geschwader to be equipped and operational with the Me 262 Blitzbomber was KG 51 Edelweiss. Pilots of the single-seater ‘fast bomber’ used mainly explosive anti-personnel Red ^ anti. aircraft batteries clustered bombs or AB 250 or AB 500 containers against around ground targets caused increasingly pin-pointed targets and troop concentrations serious problems for Ju 87 crews,

behind the Western Front. On 20 July 1944

Einsatzkommando Edelweiss began attacking Allied troop formations in Normandy. In Operation Bodenplatte on 1 January 1945 during the Ardennes Offensive the unit bombed the airfields at Eindhoven and s’Hertogenbosch successfully, and maintained an offensive presence to the end of the campaign, covering the German divisions as they retreated. From mid-January they attacked targets west of the Rhine.

On 7 January the Geschwaderstab at Rheine (Major Wolfgang Schenk) had 4 Blitzbombers while I./KG 51 had 30, with 9 more on the way. II. Gruppestab had 3, but the inventory of the entire Gruppe was only 10, and 10 pilots.

III. Gruppe had been disbanded in September 1944 while IV./KG 51 had been re-designated IV.(Erg)/KG 51. This was a pilot supply Gruppe which had been at Erding since January and was disbanded in April. Only I. and II./KG 51 carried out operations. A few days after 7 January the total of Me 262s available was 58. Despite a heavy air raid at Rheine airfield, Me 262 attacks continued against targets in the Rhineland and western Ruhr. In attacks on ground targets around Kleve, 55 Me 262s of Stab and I./KG 51 took part. These massed operations failed to hold back the endless British columns. By the end of the month the attacks were ebbing for lack of fuel.

J

On 22 February, 34 Me 262s of KG 51 set out for Kleve protected by over 100 piston-engined fighters. Several KG 51 pilots were lost on this operation while a number of aircraft dropped out with turbine defects. The expected operational life of 40 hours for these engines was optimistic. Poor maintenance and inexperienced ground staff contributed to avoidable losses amongst the Edelweiss pilots.

After the bridge at Remagen fell almost intact into US hands on 7 March, early next morning the Reichsmarschall called KG 51 operations room to request volunteers to sacrifice their lives by diving bomb-carrying Me 262s into the bridge. Two pilots stepped forward but were dissuaded by their squadron commanders at the last moment. Between 13 March and 20 April, I./KG 51 used the Autobahn between Leipheim and Neu-Ulm as its operational base. Since the delivery unit of the Kuno assembly works (a factory hidden in woods near Burgau), and a similar plant near Leipheim aerodrome were nearby, this offered some limited opportunity for engine overhauls. At least two operations were flown from Giebelstadt against armour heading for Mainz, one of these against the important railway bridge at Bad Munster am Stein on 18 March 1945. These few operations fell well short of doing anything to change the situation or stop the Allied advance.

On 30 March Kammler ordered all available Blitzbombers, transferred to IX. Fliegerkorps. General der Flieger Josef Kammhuber intervened and diverted two-thirds to JG 7 and the other third to KG (J) 54 on the orders of the Luftwaffe General Staff once the Reichsmarschall had refused to hand Kammler unlimited power over IX Fliegerkorps. On 31 March jet bombers at KG 51 totalled 79, of which a number had come direct from the Leipheim production line near the Autobahn. A little later Kammler’s decision to disband the Jabo unit was overturned when Hitler ordered the resumption of ground attacks by Blitzbombers. KG 51 then received more of the aircraft, but from mid – March ever fewer were operational for lack of parts and above all fuel. The number of low-level attacks dropped, and most Allied columns arrived at their destinations unmolested.

On 18 April seven Me 262s of KG 51 attacked enemy lorries near Nuremberg, and in a skirmish with eight P-5 Is shot down one without loss. Two days later the Geschwader evacuated south as Allied troops menaced its airfields. On 20 April I./KG 51 relocated from Leipheim to Memmingen. Next day, together with JG 53 fighter pilots, a massive low-level raid was flown against long convoys near Gottingen. On 23 April two pilots attacked the bridge over the Danube at Dillingen which had been turned into a hub for the Allied advance. At this time I./KG 51 had only 12 Blitzbombers for its 43 pilots. On 25 April the last nine

|

Fighter-bomber operations entered a new dimension with the introduction of the Me 262 A-l/Bo Blitzbomber.

|

airworthy Me 262s moved to Munich-Riem, and on the 26th KG 51, after taking over nine Me 262s of the stock of 44 at JV 44, fell back on Holzkirchen where it was intended to disband the Geschwader, no further missions being considered possible.

At times it seemed possible that Jabo jets might be the way to improve matters, but the number of available Ar 234s and Me 262s was insufficient. It is, however, worth examining the role played by these aircraft.

At times it seemed possible that Jabo jets might be the way to improve matters, but the number of available Ar 234s and Me 262s was insufficient. It is, however, worth examining the role played by these aircraft.

On 28 November Kensche and Leutnant Walter Starbati flew an Re 2 twice at Larz. Starbati had previously been detached to the Zeppelin Luftschiffbau as a test pilot, and at Rechlin he appears to have received the order to test the Reichenberg personally. On 16 January 1945 Starbati flew the series-produced Re 3 (Works No. 10). After reaching speeds between 620 and 650 km/hr at 2,600 metres altitude (385—

On 28 November Kensche and Leutnant Walter Starbati flew an Re 2 twice at Larz. Starbati had previously been detached to the Zeppelin Luftschiffbau as a test pilot, and at Rechlin he appears to have received the order to test the Reichenberg personally. On 16 January 1945 Starbati flew the series-produced Re 3 (Works No. 10). After reaching speeds between 620 and 650 km/hr at 2,600 metres altitude (385—