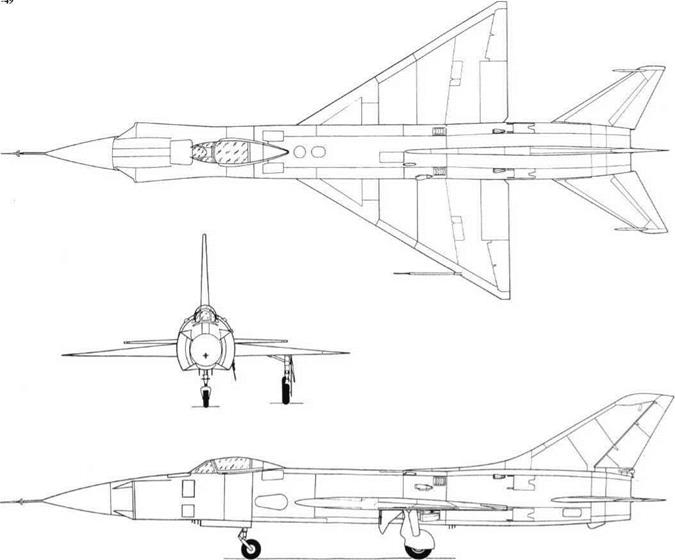

Tupolev Tu-2 Experimental Versions

|

|

Purpose: To use Tu-2 aircraft for various experimental purposes.

Design Bureau: Originally, CCB-29 (or TsKB-29) and GAZ (Factory) No 156.

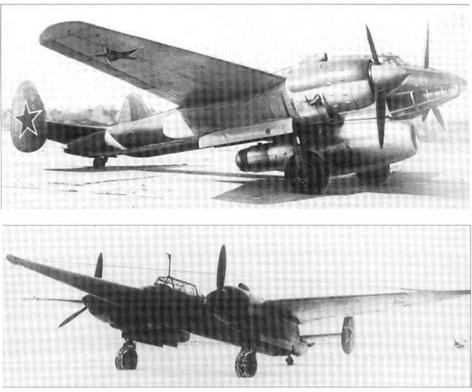

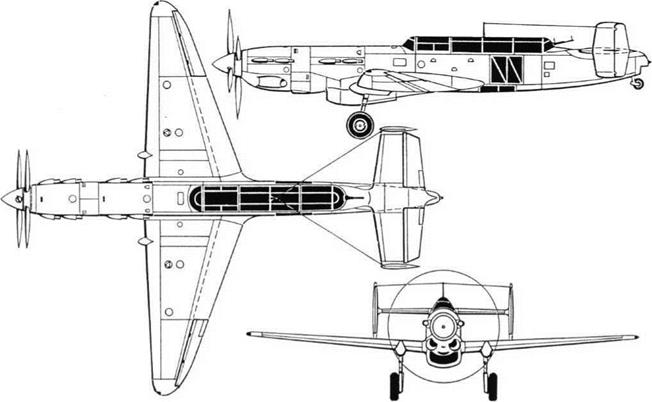

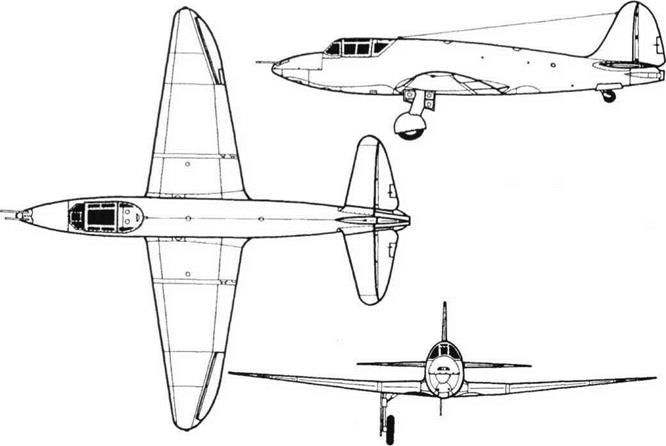

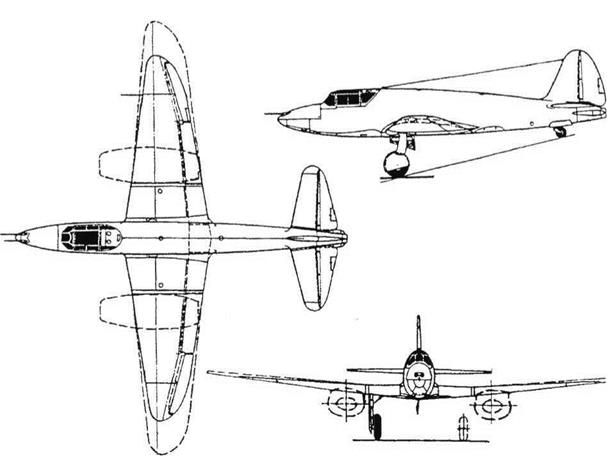

Created during A N Tupolev’s period in detention under a ludicrously false ‘show trial’ charge, the Tu-2 (previously ‘Aircraft 103’, but really the 58th ‘ANT’ design), was an outstanding multirole tactical bomber. Its ridiculous gestation, with its creator working on a drawing board in a locked cell, meant that it did not enter service until May 1942, but despite this some 3,300 were delivered from Factories 156, 166 and 125. As soon as spare examples became available they were snapped up for use as test-beds. The very first series aircraft, No 100716, was used to test the ASh-83 engine, rated at l,900hp, driving four-blade AV-5V propellers (replacing the standard 1,850hp ASh-82FN driving the three – blade AV-5V-167 or four-blade square-tip AV-9VF-21K). Maximum speed of this testbed was 635km/h (395mph) at 7,100m (23,294ft).

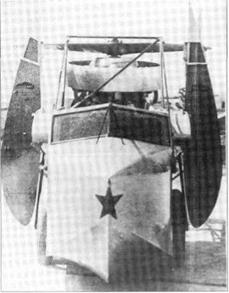

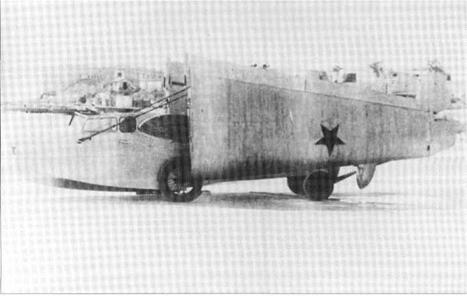

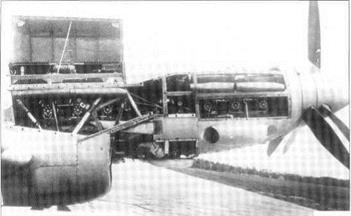

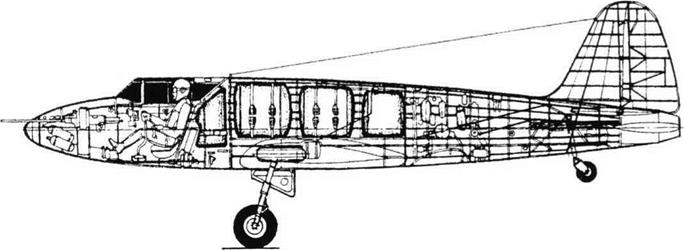

Numerous test versions appeared in 1944, including the first two of three Shturmovik (armoured ground attack) versions with special armament, all proposed by Tupolev’s armament brigade leader A D Nadashkevich. The first, actually given the designation Tu-2Sh, had its capacious weapon bay occupied by a specially designed aluminium box housing 88 modified PPSh-41 infantry ma

chine carbines (sub-machine guns). These fired standard 7.62mm pistol ammunition, and all fired together pointing obliquely down at a 30° angle. The obvious shortcoming was that, even though the drum magazines held 71 rounds, they were quickly emptied.

The second 1944 Sh version had a massive 75mm gun under the fuselage, reloaded by the navigator. Two more ground-attack versions appeared in 1946. The first had the devastating forward-facing armament of two 20mm ShVAK, two NS-37 and two NS-45. The 37mm gun was 267mm (101/2in) long and weighed 150kg (33lib). The 45mm version had a shorter barrel but still fired its 1.065kg (2.35 Ib) projectiles at 850m (2,790ft) per second, and weighed 152kg (335 Ib).

The last of these variants was the two-seat RShR, or Tu-2RShR. This was a dedicated anti-armour aircraft, carrying a high-velocity 57mm RShR automatic cannon with the barrel projecting ahead of the metal-skinned nose and fitted with a prominent recoil brake.

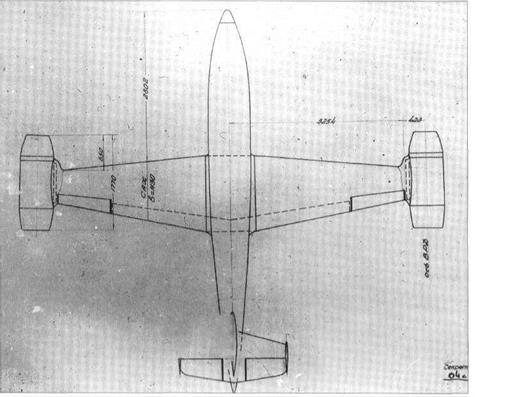

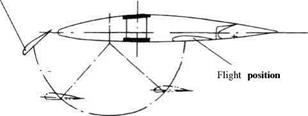

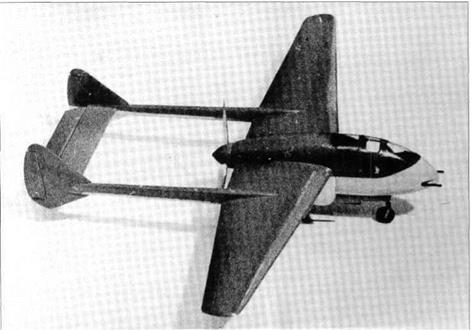

The most startling modification was the Tu-2 Paravan (paravane). Two of these were built, to test a crude way of surviving impact with barrage-balloon cables. A special cable woven from high-tensile steel was run from one wingtip to the other via the end of a monocoque cone projecting over 6m (20ft) ahead of the nose. The nose and wingtips were reinforced. First flown in September 1944, this lash-up still reached 537km/h (334mph) despite the strange installation and

a 150kg (331 Ib) balancing weight in the tail. These trials were not considered to have been successful.

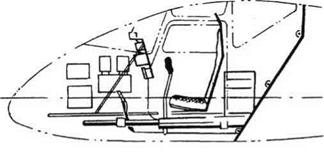

Yet another 1944 modification was the Tu-2K (Katapult), fitted with test ejection – seats. The first Tu-2K fitted the test seat in the navigator’s cockpit just behind the pilot. A second ejection-seat tester had the experimental seat mounted in an open cockpit at what had been the radio operator’s station in the rear fuselage.

In early 1945 the Type 104 radar-interception system began flight testing (the first to be airborne in the Soviet Union). The system had been designed from 1943, by a team led by A L Mints, and the Type 104 test aircraft had begun flighttesting on 18th July 1944 but with the vital radar simulated by ballast. The pilot had a modified sight, which was later linked to the radar, and fired two VYa-23 cannon installed under the forward fuselage. The rear fuselage was faired over and contained nothing but a balancing mass.

The designation Tupolev Tu-2G was applied to several Gruzovoi (cargo) conversions. It appears that all of these were experimental, carrying special loads either in the remarkably large bomb bay or slung externally, and in many cases the load was dropped by parachute. No fewer than 49 GAZ – 67b armoured reconnaissance cars were dropped, the Tu-2G in this case being limited to a height of 6km (19,685ft) and a speed of 378km/h (235mph).

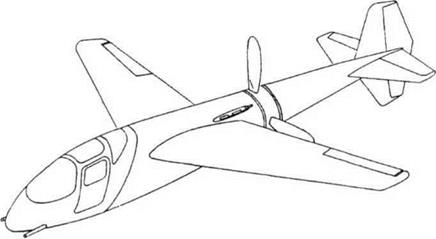

As explained in the stories of the Pe-2 and Pe-8 experimental versions, the German Fi 103 (‘V. 1’) flying bomb was the basis for a large Soviet programme of air-launched cruise missiles in the immediate post-war era. One ofthe later variants was the 16Kh Pri – boi (surf, breaking waves). The fact this was fitted with twin engines meant that it could be carried under the Tu-2. The first modified Tu-2 launch aircraft began testing at LII on 28th January 1948, and live missile launchings took place on the Akhtuba range between 22nd July and 25th December 1948, testing the D-312 and D-14-4 engines and various electric or pneumatic flight-control systems. The Tu-2 launch aircraft continued in the

process of refining guidance and improving reliability until at least 4th November 1950, by which time the Tu-4 was being modified as carrier aircraft with one missile under each outer nacelle. The WS rejected the 16Kh on grounds of poor accuracy, and eventually the argument reached Stalin who shortly before his death terminated this missile.

Experimental Tu-2 aircraft were also used to develop air-refuelling.

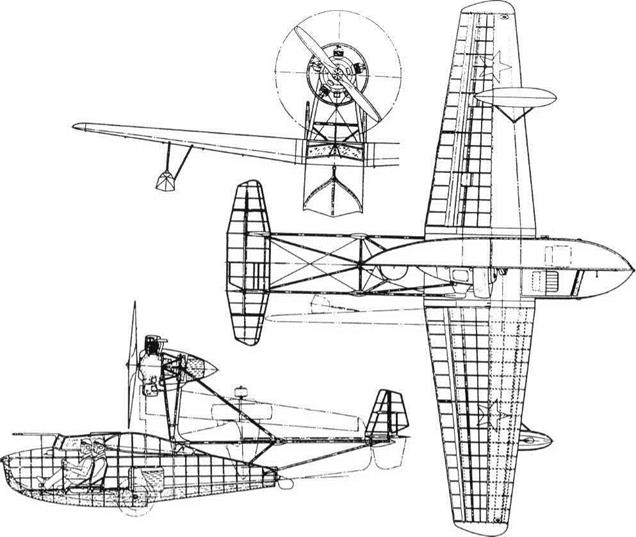

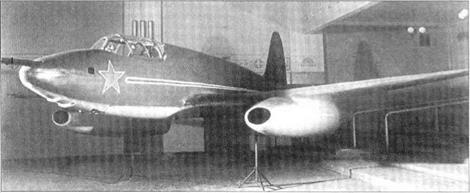

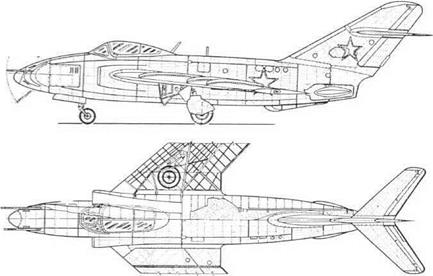

Not least, in the immediate post-war era the Tu-2 was the most important aircraft converted to air-test turbojet engines. Occasionally the designation Tu-2LL (flying laboratory) was used, but one of the most important was (possibly unofficially) designated Tu-2N,

because it was allocated to test the imported Rolls-Royce Nene. This required the test engine to be mounted in a nacelle of large diameter (basic engine diameter 1.26m, 4ft 11/2in). Later more than one Tu-2 was used to test Soviet RD-45 and VK-1 derivatives of the Nene, including variants with an afterburner. However, these were all preceded by aircraft, some of which had been Tupolev Type 61 prototypes, which were converted to test captured German axial engines: the BMW 003A (Soviet designation RD-20) and the Junkers Jumo 004B (Soviet designation RD-10). Another 61 prototype was used to test the first Soviet turbojet to fly, the Lyul’kaTR-1, in 1946.

302P

302P

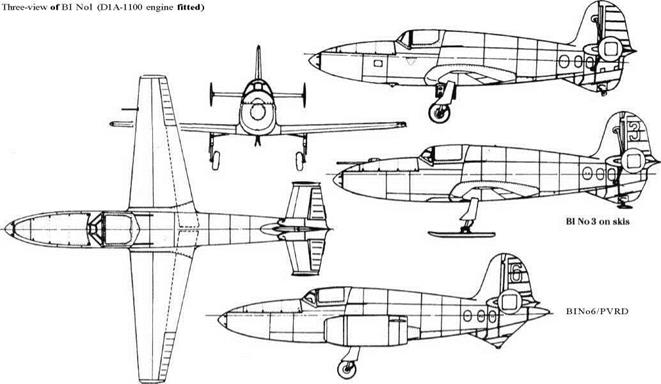

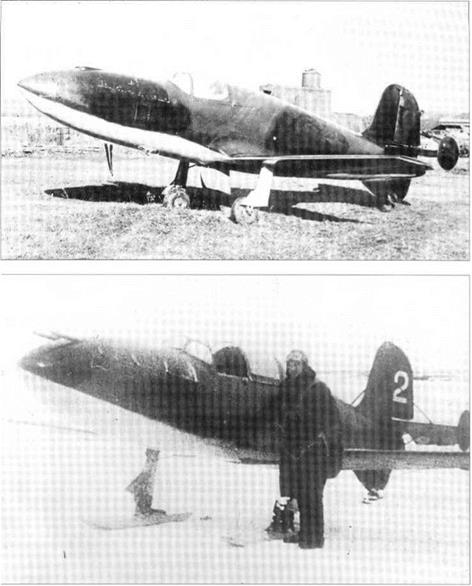

This terminated the delayed plan to build a production series of 50 slightly improved aircraft, but testing of the prototypes continued. Until the end of the War these tested various later Dushkin engines, some with large thrust chambers for take-off and combat and small chambers to prolong the very short cruise endurance (which was the factor resulting in progressive waning of interest). Other testing attempted to perfect a sealed pressurized cockpit. To extend duration significantly BI No 6 was fitted with a Merkulov DM-4 ramjet on each wingtip. These were fired during test in the CAHI T-101 wind tunnel, but not in flight.

This terminated the delayed plan to build a production series of 50 slightly improved aircraft, but testing of the prototypes continued. Until the end of the War these tested various later Dushkin engines, some with large thrust chambers for take-off and combat and small chambers to prolong the very short cruise endurance (which was the factor resulting in progressive waning of interest). Other testing attempted to perfect a sealed pressurized cockpit. To extend duration significantly BI No 6 was fitted with a Merkulov DM-4 ramjet on each wingtip. These were fired during test in the CAHI T-101 wind tunnel, but not in flight.