All subsequent Apollo landings included time to deploy a full ALSEP, each consisting of a varying set of instruments cabled to a central station, all of it powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG). This was an early example of the type of power supply that would energise a generation of probes to the outer planets.

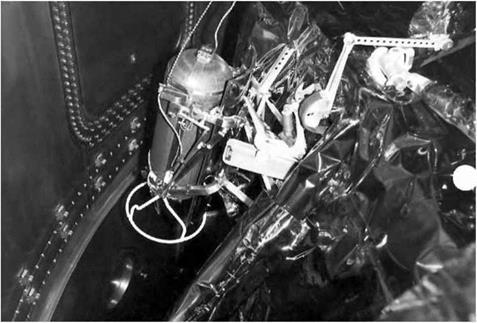

The Apollo RTGs used the radioactive decay of plutonium-238 to generate heat which was directly converted to electricity by an array of thermocouples. The presence of plutonium on the spacecraft had certain repercussions. It could not travel to the Moon in the RTG for fear of contamination if there were to be an accident near Barth. Instead, it was packaged into a fuel element or capsule which was transported to the Moon inside a graphite cask mounted vertically on the outside of the descent stage where it could radiate its heat. This cask was strong enough to withstand re-entry through Barth’s atmosphere and, thanks to this ability, the Apollo 13 plutonium now lies at the bottom of the Tonga trench in the Pacific Ocean.

Once on the Moon, it was the LMP’s task to remove the plutonium fuel capsule from its cask and insert it into the body of the generator. Alan Bean w as the first to try this and ran into problems when reality failed to match any Barth-bound trials. First he hinged the cask down to gain access to the removable dome at one end. then he removed it with a special tool.

’’There you go,” said Pete Conrad encouragingly.

”It came off beautifully.” said Bean. ‘ [I’ll] put the tool and the dome aside.”

This had started well. Next he had to engage the capsule removal tool. “Go ahead,” said Conrad.

“There you go.” commented Bean. “Sliding right in there. Okay. [I’ll] tighten up the lock.”

With the tool firmly engaged, Bean pulled on the capsule, only to discover that it wasn’t going anywhere. “You got to be kidding,” he exclaimed.

“Make sure it’s screwed all the way down,’’ suggested Conrad.

Bean was caught between wanting to give it a good yank but not wanting to break the mechanism that attached the tool to the capsule. Gear that w? ent to the Moon was built as light as possible. There wouldn’t be much strength in reserve.

“Thai could make a guy mad. you know it?” moaned Bean.

“Yup,” replied his commander.

“Let me undo it a minute, and try it a different way.”

“Yup.”

“It can really get you mad."

|

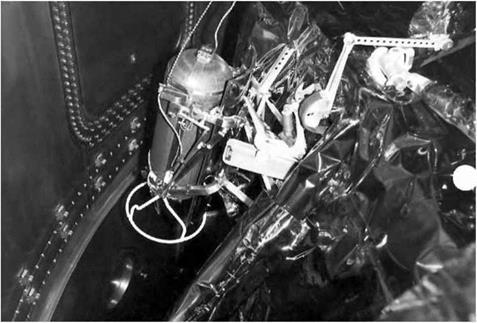

The graphite cask that held the plutonium fuel capsule for Apollo 17’s RTG, seen here attached to Challenger inside the SLA before launch. (NASA)

|

|

Bean reinserted the tool with its prongs rotated to use different slots.

Bean reinserted the tool with its prongs rotated to use different slots.

"You guys got any suggestions?” asked Conrad of the folks in Houston.

"I just get the feeling that it’s hot and swelled in there or something,” Bean said as he tried again to extract the capsule. "Doesn’t want to come out. I can sure feel the heat, though, on my hands. Come out of there! Rascal.”

The capsule was seated within two steel rings that held it away from the graphite cask. It seemed that, with it giving off 1.5 kilowatts of heat, the expansion of the arrangement was holding it snug on the rings.

"You know, everything operates just exactly like it does in the training mock-ups and up at GE (General

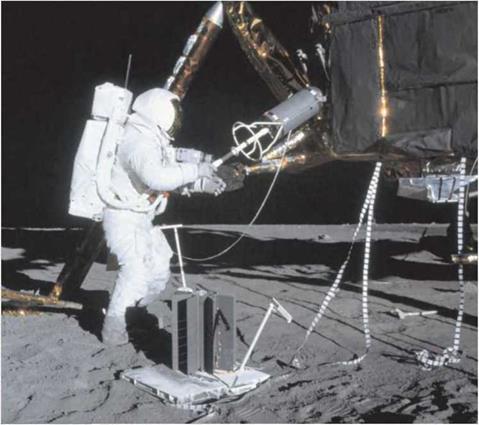

|

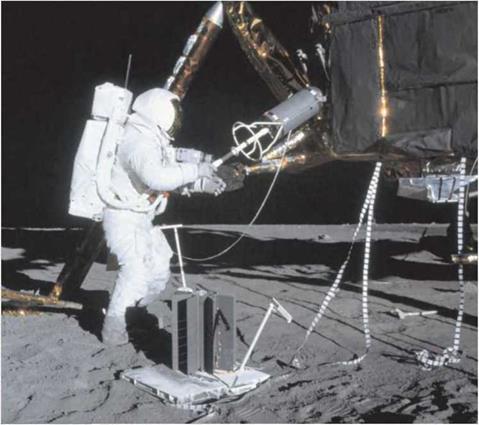

Alan Bean attempts to extract the fuel capsule from Intrepid’s cask. Beside him is the black-finned RTG ready to take the capsule. (NASA)

|

Electric Corporation). The only problem is, it just won’t come out of the cask. I am suspicious that it’s just swollen in there or something and friction’s holding it in. But it’s such a delicate tool, I really hate to pull on it too hard.”

Unfortunately engineers had not fully taken account of the length of time that the capsule would sit in its cask from Florida to the Moon, its 700°C heat soaking the steel mounts.

Bean piped up. “Go get that hammer and bang on the side of it.”

“No. I got a better idea,” said Conrad. “Where’s the hammer?”

“That’s what I said.”

“No, no. But I want to try and put the back end in under that lip there and pry her out. Let me go get the hammer. Be right back.” Conrad’s idea was to use the hammer’s blade to lever the capsule out.

“Let me get the tool off,” said Bean as he felt the capsule’s heat move along the handle. “It’s starting to warm up.” He disengaged the tool as Conrad went around the LM. They were not unduly bothered by the radiation from the capsule. It was alpha radiation and as such, was stopped by a small amount of material. They would not be exposed to it for long anyway. Their real concern was that the thermally hot capsule might damage their suits. They had to use the tool to extract it. Once Conrad had retrieved the hammer. Bean re-engaged the tool with the element. They were both leaning towards a little percussive persuasion.

Bean spoke first. "Now, my recommendation would be pound on the cask.” He preferred that Conrad not use the hammer’s blade on the capsule. As Bean pulled on the tool, Conrad began to repeatedly hit the side of the cask with the hammer.

”Hey, that’s doing it!” yelled Bean excitedly as the cask began to yield its contents. "Give it a few more pounds. Got to beat harder than that. Keep going. It’s coming out. It’s coming out! Pound harder/’

“Keep going/’ commanded Conrad to the balky capsule.

‘’Come on, Conrad!” laughed Bean.

"Keep going, baby."

“Thai hammer’s a universal tool.”

“You better believe it/’ cheered Conrad.

With every thump, the capsule edged out until, after a few centimetres, it came away easily. To Conrad’s giggles. Bean swung it over to the RTG unit.

"That’s beautiful. That’s Loo much.” said Bean.

“Well done, troops/’ congratulated Ed Gibson, Capeom in Houston.

“We got it, babe!" explained Bean. “It fits in the RTG real well! It’s just the cask was holding in on the side. Don’t come to the Moon without a hammer.” He brought the hammer home to Earth and now uses it to texture his paintings in his post-Apollo life as an artist.

Deployment of the ALSEP required a reasonably flat site a few hundred metres from the LM. The complete kit was mounted on two pallets and stored on rails in the LM’s descent stage. Once lowered to the ground by pulleys, the packages were hung on a bar bell and carried to the site. The layout was roughly star-shaped with ribbon cables that radiated out from the central station to the various instruments. Each cable was on a reel which fed out both ends simultaneously. There were often stringent constraints on the placement of each instrument, requiring care to avoid interference between instruments and to minimise heat conduction with the ground. For example, the magnetometer had to be clear of other instruments that contained magnets. Also, the seismometer was mounted on a stool surrounded by a reflective Mylar skirt that kept the Sun from heating the ground because the expansion and contraction from the heating cycles w’ould have added noise to the instrument’s output. However, the skirt itself routinely added unwanted signals each morning when the Sun first hit it and caused it to flex and buckle in the heat.

Prior to deployment, the various instruments were attached to their pallet by ‘Boyd bolts’, spring-loaded fasteners that required a crewman to insert the end of their universal hand tool (UHT) and give a fifth of a turn to release them. To help the crew7, each bolt had a collar that guided the tool to the bolt. In general, the bolts worked well but on some occasions, what had seemed simple on Earth became much more difficult in the dust and light gravity of the Moon.

“Another one of those beautiful Boyd bolts is all full of dust,” muttered Shepard

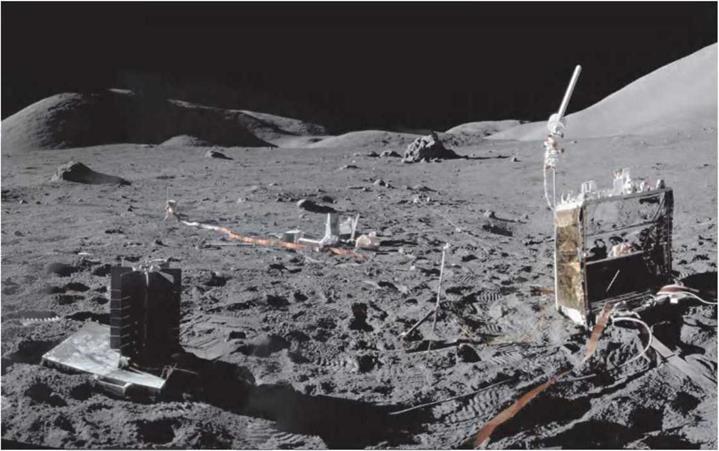

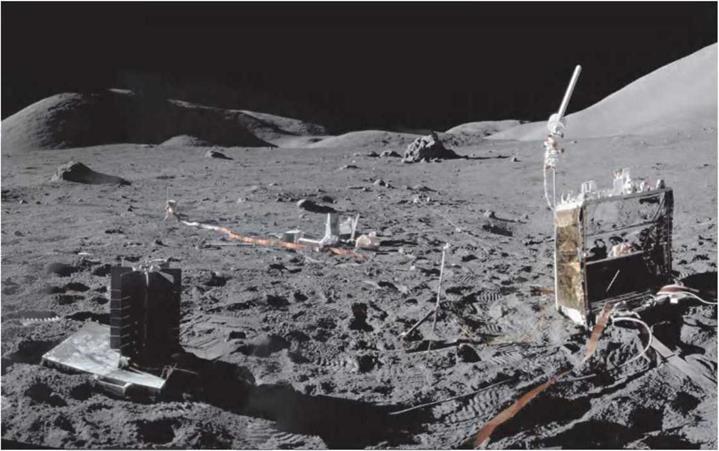

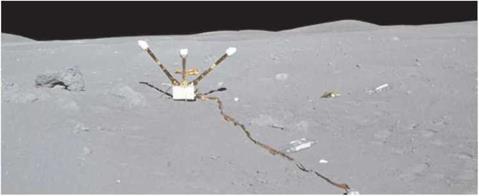

Assembled panorama of Apollo 17’s ALSEP after deployment. RTG is on the left, central station to the right with its antenna aimed E <i+hward. (NASA)

sardonically as he tried to release a small instrument, the supra thermal ion detector, from its pallet.

‘’Yep,” agreed Mitchell. "’Everything else is going to be full of dust before long. Be filthy as pigs."

Shepard first tried the obvious solution. "Tm going to have to lift it up and shake the dust out of that Boyd bolt; I can’t get it otherwise. Let’s just turn it upside down and shake it.’’

As they lifted it. parts fell away. "Well, there’s a lot of Boyd bolts falling off,’’ said Mitchell, referring to the parts of the bolts that Shepard had already unfastened.

"Yeah, but them’s not the ones we’ve got the problems with. Okay, flop it over a minute."

‘"That’ll do it?" asked Mitchell hopefully.

"No, it’s still not clear.’’

Shepard was having problems on three levels. Lunar dust gets everywhere and having found its way into the Boyd bolt, its cohesive nature in the vacuum helped it to stay there. Additionally, the weakness of the lunar gravity gave little assistance in clearing the bolt’s sleeve, even when Shepard turned it upside down. The situation was exacerbated by the bolt being relatively inaccessible and, as Mitchell would later explain, it was difficult to see what was happening. “On the lunar surface, there’s no air to refract the light in there. So, it’s either shadow or it’s light and, unless you’ve got a direct sunlight on it, there’s no way in hell you can see anything. That’s an amazing phenomenon on an airless planet. It’s amazing how much we count on reflected and refracted light here. But there, unless you had it directly in sunlight, it was just pitch black. And that’s what he was wrestling with, there. The dirt was packed in around it and, besides that, he couldn’t see dowm in there unless we picked it up, physically, and twisted it and held it so we could get it in the sunlight."

That one bolt cost Shepard nearly ten minutes before he finally got it loose. David Scott later discussed how important it was for something that small to work correctly. "In a training context, especially [as Apollo 12 backup commander]. I remember trying to get the Boyd bolts to work, and they would hang up. One would hang up, and you couldn’t deploy the ALSEP. Or, the UIIT’s hexagonal probe that goes into the socket w’ould sort of strip and get w’orn and you couldn’t turn it. And, if you turned it too hard, you’d strip the edges. The Boyd bolts were challenges. I think all ours w’orked just fine. But the UIIT and the Boyd bolts w’ere a big deal; because, if it didn’t work, then you didn’t get that piece of the ALSEP up. And there were a lot of Boyd bolts."

Across the six missions that landed, crew’s deployed a large number of instruments as part of the ALSLP or as standalone experiments. Seismology was a popular topic, with passive seismometers being carried on most missions. Some missions included active seismometry. with small explosive charges being set up to provide calibrated shockwraves that w’ould help to profile the local subsurface. Magnetometers sensed the local magnetic held which, on the Moon, was dominated by its monthly passage through Earth’s magnetotail. However, because some of the Apollo 11 rocks proved

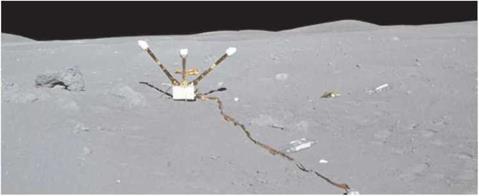

|

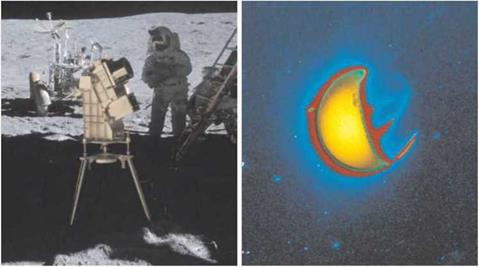

The magnetometer experiment of the Apollo 16 ALSEP. (NASA)

|

to be magnetic, some later missions included a portable magnetometer to measure remanent magnetic fields at points along a traverse. Many experiments tried to sense and characterise the various particles that comprised what little atmosphere the Moon possessed. Most of these were from the solar wind or from the rocket exhaust of the spacecraft, but there was also the question of whether the change from night to day, and the resulting rise in ultraviolet exposure caused tiny particles of charged dust to levitate for a while.

There were experiments on the mechanics of the lunar soil which acted in ways that were not foreseen. Though the top layer was extremely loose and powdery, its characteristics changed markedly just a few centimetres below the surface. Millions of years of slow settlement had caused it to become extremely tightly packed and crews sometimes found it difficult to drive in items like flagpoles and the solar wind collector. Trenching experiments showed that the vacuum and the very finely ground nature of the powder made it remarkably cohesive and able to support steep sides. Even Buzz Aldrin’s famous bootprint photograph showed how well the powder could hold an impression.

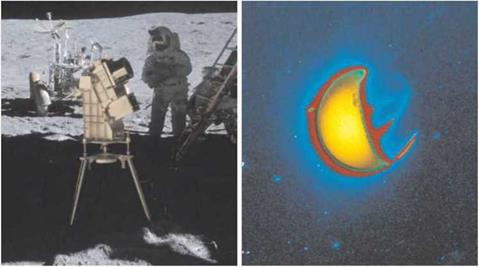

There was an ultraviolet telescope on Apollo 16, a device for measuring the local gravitational field mounted on Apollo 17’s rover, and experiments to determine the electrical properties of the lunar surface. Add to all this the intense expeditions to photograph, document, sample and generally geologise across their site, this feast of science kept all the Apollo surface crews extremely busy for their precious hours walking on the Moon. One particular ill-starred experiment served to teach everyone about the difficulties of trying to carry out science in a vacuum, under an unfiltered Sun into a poorly understood, extremely dusty and abrasive soil while wearing in an awkward pressure suit with limited visibility. This was the heat-flow experiment.

Drill problems and the heat-flow experiment

Geophysicist Marcus Langseth was good at taking Earth’s temperature and now he had a chance to take the Moon’s. More specifically, he wanted to accurately

|

Left, John Young with Apollo 16’s UY telescope. Right, UV image of Earth. (NASA)

|

measure the temperature of the lunar soil at various depths. From these measurements, he hoped to calculate how much heat was flowing out of the Moon’s interior and infer whether its core is still molten. He designed an experiment for Apollo 13’s ALSEP that would place temperature probes into drill holes. The equipment burned up in Earth’s atmosphere after that mission’s LM had served as a lifeboat for its crew.

Langseth had to wait over a year for the Apollo 15 crew to try again. Using the father of the cordless drill, the experiment required two holes, each nearly three metres deep into which the probes would be inserted. Separate from the experiment, the drill would also be used to extract a deep core of material that would give geologists a record of the depositional layering of the soil potentially going back hundreds of millions of years.

Scott quickly found the drilling to be hard going and could only get the first hole down to 1.6 metres. He tried putting his weight on the drill but in the Moon’s weak gravity, this provided little push and, if anything actually worked against the design of the drill stems and their helical external flutes. At any rate, the designers had not taken sufficient account of the nature of the Moon’s surface. Although the Moon is draped in a blanket of finely ground-up rock – the regolith – which is many metres deep at the landing sites, the highly compacted nature of all but the uppermost few centimetres made it more like hard rock. Worse, the flutes at the joins of the drill stems had been narrowed to strengthen those joins but, with the dust unable to go anywhere else, it caused the stems to jam. Mission control agreed that Scott should place the probes in the existing hole even though it compromised the quality of the experiment. The second hole fared worse and at one metre, they decided to revisit it the next day. On returning to the site, Scott tried to lift the drill and rotate it to help clear the flutes but unbeknownst to him this actually caused the bit to disengage

|

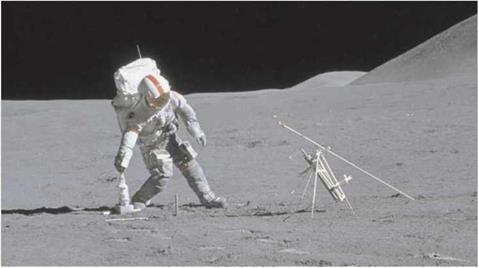

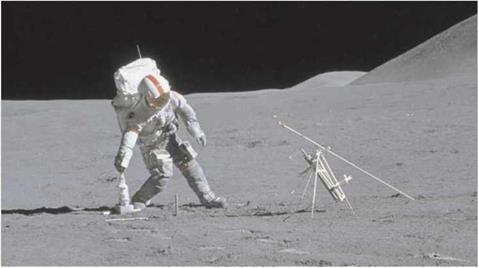

David Scott sets down the drill during operations to emplace the heat-flow experiment. (NASA) "

|

from the stem above. Subsequent drilling with the hollow upper stem merely created a core running down alongside and when Scott inserted the probes they penetrated no further than about one metre.

With the heat-flow probes less than ideally placed, Scott began to drill a deep core sample using hollow stems which meant the material in the hole would be kept rather than pushed aside. Also, the flutes were of uniform depth and much faster progress was made. Scott readily reached 2.4 metres in depth, much deeper than the other two holes but by this time, they needed to return to the LM and leave the extraction to the final day. Much time and frustration had already been expended on the drilling.

On the final day, Scott learned that extraction of the deep core was to take precedence over their final drive to Hadley Rille and a feature known as the North Complex, a possibly volcanic site of some interest to Scott and the geologists. Usually rover drives came first so the crews would have more consumables available in case they had to walk back from a stalled vehicle. The decision to favour the drill meant that there would be no visit to the North Complex. However, when they tried to remove the core, it proved difficult to budge. Both Scott and Irwin had to work to extract the core, first by pulling hard on the drill’s handles, and eventually putting their shoulders under the handles and shoving so hard that Scott managed to injure his shoulder. It was a measure of the confidence that the crews had in their suits that they felt they could expend maximum physical effort without fear of a rip dumping their air.

"It shows how tough and durable the things were,” remembered Scott when reviewing the incident years later. "I’m really surprised that somebody in the back row in Houston didn’t get real squeamish about all of this. I’m surprised some boss didn’t just say. ’Hey, just knock that off.’ because they could hear us grunting and groaning – two guys on the Moon in pressure suits doing this kind of stuff. In retrospect, not smart, from a safety point of view.”

How ever, their suits included systems to warn of problems with the air pressure or cooling. ‘’Only if a tone comes on do you do something.” continued Scott. “As long as there are no tones, you work as you would work on the Earth and you never really think about [the dangers], Houston, that’s their job. To sort of pace us and guide us, because once we’re out in the suits, boy, it’s very comfortable."

Eventually, Scott and Irwin extracted the deep core but Scott’s troubles were not over and he was getting frustrated at the time being spent on it. "Joe, I haven’t heard you say yet you really want this that bad.” Joe Allen was the tactful Capcom in mission control. As part of his job, he acted as a go-between for the crew and the geology team in the science back room. ‘’Tell me you really want it this bad.” implored Scott. “It’s hard for me to say. Dave," was Allen’s wistful reply.

The six-part core stem, including a treadle that had helped guide the stem into the soil, all had to be taken apart for return to Earth. To help, a simple wrench vice that gripped in one direction was on the rover. Scott was having difficulty getting it to work. ‘‘This vice just won’t hold. There’s something wrong with it." They needed that wrench because a suited hand does not have much grip. It is already working against the suit pressure trying to straighten it “My hand wrench works okay. The one on the back of the [rover] doesn’t seem to want to work for some reason. It may just be because of the threads on the stems. I just can’t get them broken apart!” As Scott struggled with the stem in the vice, it dawned on him what the problem was. "I hate to tell you. Jim, but that… Oh boy! This vice is on… I swear it’s on backwards.” In fact, a reversed diagram in the assembly manual had thwarted them. The wrench had indeed been mounted back to front.

With Irwin’s help. Scott managed to separate half of the segments, even though it meant gripping the stem’s sharp flutes, yet the final three refused to come apart.

“We might be able to return it just like that.” suggested Irwin. Although it was 1.5 metres long, they would be able to get it in the LM.

“I don’t know where we’re going to put it in the command module.” said Scott. "I guess we ought to take it back. There’s more time invested in that than anything we’ve done.”

When the deep core reached Earth, it was immediately x-rayed which revealed 58 distinct layers within the core. Grant Heiken, a scientist who painstakingly analysed each layer, grain by grain, described it as the most valuable sample returned from the Moon.

The Apollo 15 heat-flow experiment gave good results despite its problems and created enough interest in Langseth’s experiment for another to be taken on Apollo 16. All the lessons from Scott’s battle with the drill and wrench had been learned. Using redesigned drill stems, Duke had no problem drilling the holes and inserting the temperature probes.

“Mark has his first one. announced Duke. "All the way in to the red mark [on the rammer] on the Cayley Plain.”

“Outstanding!” replied Tony England. “The first one in the highlands.”

Moments later, John Young lifted a package away from the central station and as he walked, his feci got caught up with the cable leading to the heat-flow electronics package.

“Charlie."

“What?"

“Something happened here."

“What happened?"

“I don’t know." said Young. “Here’s a line that pulled loose."

“That’s the heat-flow," Duke informed. “You’ve pulled it off."

“God almighty." Young’s spirits dropped like a stone as he went to examine the damage closely. The wires at the end of the cable had been torn from its connector where it was plugged into the central station.

“Well, I’m wasting my time," said Duke as he realised there was no point in drilling the second hole for the heat-flow probes.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t even know, said Young. "Agh; it’s sure gone."

“Okay, we copy," said England in Houston as the engineering back rooms began to crank up in a futile effort to resurrect the experiment. “I guess we can forget the rest of that heat flow."

“Yeah," replied Duke. “I’ll go do the [deep core]. Oh. rats!"

In fact, it was surprising there were not more accidents like this. Having the RCU mounted on his chest afforded the astronaut almost no visibility of his feet and the numerous layers in the suit’s construction severely attenuated any sense of touch. He constantly had to work against the internal pressure and its tendency to return the suit to one stance. This made it difficult for Young to have seen or even to have felt the snagging cable. Additionally, in lunar gravity cables tended not to lie as flat as they would on Earth and they ’remembered’ their coiled-up shape to form numerous loops spiralling across the lunar dust.

After more than 2 ‘/■ years. Marcus Langseth finally triumphed when his heat – flow experiment was fully installed at Taurus-Littrow by the Apollo 17 surface crew. The measurements from the two sites where emplacement was successful showed that the Moon has little residual heat of its own. What heat it has is produced by radioactive decay in the topmost few hundred kilometres but it is insufficient to cause substantial melting of the lunar mantle.

Bean reinserted the tool with its prongs rotated to use different slots.

Bean reinserted the tool with its prongs rotated to use different slots.