X-ray fluorescence spectrometer

The Moon has little protection from the Sun’s constant output of x-rays that wash over its day-lit surface and strike whatever gets in their way. When they strike certain elements, particularly those at the lighter end of the Periodic ‘fable, they cause the atoms to re-emit or fluoresce x-rays in certain well-defined energies. Therefore, by comparing the spectral make-up of x-rays from the Sun with x-rays from the sunlit lunar surface, scientists could identify some of the elements in the topmost layer. This was a particularly powerful technique because it could sense those elements that formed the bulk of rocky planets, namely oxygen, silicon, aluminium, magnesium and iron. Apollo’s x-ray spectrometer therefore consisted of two detectors, one of which w’as built into the SIM bay to receive x-rays from the Moon. The second was on the opposite side of the service module where it measured the x-ray flux from the Sun.

It wasn’t long after the SIM bay w-as used for the first time on Apollo 15, that a comparison was made of the signals from the x-ray spectrometer with altitudes from the laser altimeter revealing an important clue to the Moon’s history. Scientists had noticed that a graph from the laser altimeter showing the surface elevation beneath the CSM bore a strong resemblance to another from the x-ray spectrometer showing the concentration of aluminium along the same path. The aluminium concentration declined in low-lying terrain. The significance of this lies in the fact that aluminium is a relatively lightweight element. The discovery that its concentration was greater in the highlands strongly implied that, at one time, the Moon must have been largely molten to allow that element to rise to the top. This ran counter to one of the two popular theories about the Moon’s genesis that were vigorously debated at that time.

One school, dubbed the ‘cold Mooners". believed that the Moon accreted from the solar nebula without generating significant internal heat, that the large basins on its surface w’ere made by impacts and that the maria were splashes of melted rock w’hich pooled in low-lying areas. The ‘hot Mooners’ believed that the interior of the Moon was sufficiently hot for thermal differentiation into a core and a mantle, and that it had later undergone substantial surface volcanism. creating the maria.

Both schools had grasped elements of the truth. Current theories contend that upon its formation, the Moon was so hot that its mantle was completely molten in what is descriptively called a magma ocean. Within this fluid mass, gravity allowed the various constituents of the magma to migrate either up or down according to their weight, such that the fresh crust tended to have a high concentration of aluminium. The fact that strong evidence of this chemical differentiation is still extant today is testament to the extraordinary antiquity of the lunar surface when compared to that of Earth.

Mass spectrometer

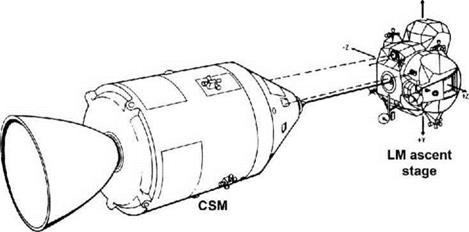

Mourned on the end of a boom to place ii clear of the spacecraft was the mass spectrometer. It was designed to characterise an)’ lunar atmosphere by measuring the atomic weight of the atoms and molecules that entered an aperture on one side of the instrument. They were promptly electrically charged, or ionised, by electrons from a filament source. Л magnet then diverted the path of the resultant ion stream towards a pair of detectors. Simply stated, the heavier an atom or molecule, the more resistant is its motion to change by an applied magnetic field. By measuring the deflection of the particle stream, the masses of its constituent parts could be determined.

When it was deployed out of the SIM bay, its inlet aperture faced away from the bulk of the CSM and in the same direction as the engine bell in an attempt to shield it from the gases that emanated from the spacecraft. During its time in lunar orbit, the instrument was flown with the inlet either facing the direction of travel or facing backwards. The hope was that differences between the two modes of operation would allow scientists to discriminate between atoms that were genuinely part of the Moon’s atmosphere (which should Lend not to enter when the inlet was facing backwards) and those that were coming from the spacecraft (which would enter from either direction).

In practice, little difference was detected whichever way the inlet faced, implying that most of what was being detected was essentially pollution from the spacecraft. This supported, on a global scale, the same results that researchers were finding from ALSEP experiments placed by Apollos 12, 14. 15 and 17. These were deluged with contaminants from the Apollo spacecraft, which made it very difficult to extract natural data from their results. This was hardly surprising considering that estimates for the total mass of the natural lunar atmosphere were around 10 tonnes – a figure very similar to the quantity of gases released during each Apollo mission, mostly from operation of the descent and ascent engines. Essentially, each Apollo flight temporarily doubled the mass of the entire lunar atmosphere.

The major result to come from this instrument was that there is a small degree of outgassing of radon at various locations on the Moon, especially in the vicinity of the prominent crater Aristarchus – a result confirmed a generation later by the Lunar Prospector probe. Interestingly, Aristarchus, which is also one of the brightest places on the Moon, was the locale for some of the reported emanations seen by telescopic observers. These tentative indications of possible ongoing lunar activity should be seen in the light of studies of a crater, Lichtenberg, on the western side of Oceanus Procel – larum. This crater exhibits a ray system that is believed to be just less than a billion years old, which is quite young by lunar standards. Yet, on a world where most of the basalt is much older, a distinctive dark lava flow has obliterated much of its southern ray system. From this evidence, and as far as is known, the final gasps of lunar volcanism occurred about 800 million years ago. To put this into a terrestrial context, this is 300 million years before complex multicellular life appeared on Earth.

The major result to come from this instrument was that there is a small degree of outgassing of radon at various locations on the Moon, especially in the vicinity of the prominent crater Aristarchus – a result confirmed a generation later by the Lunar Prospector probe. Interestingly, Aristarchus, which is also one of the brightest places on the Moon, was the locale for some of the reported emanations seen by telescopic observers. These tentative indications of possible ongoing lunar activity should be seen in the light of studies of a crater, Lichtenberg, on the western side of Oceanus Procel – larum. This crater exhibits a ray system that is believed to be just less than a billion years old, which is quite young by lunar standards. Yet, on a world where most of the basalt is much older, a distinctive dark lava flow has obliterated much of its southern ray system. From this evidence, and as far as is known, the final gasps of lunar volcanism occurred about 800 million years ago. To put this into a terrestrial context, this is 300 million years before complex multicellular life appeared on Earth.