Providence soon handed Arnold the opportunity to map out a wartime strategy based on strategic bombing. The new Chief of the aaf quickly formed an “air staff” that resembled the Army’s General Staff. He asked forty-eight-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Harold Lee George, who commanded the Second Bombardment Group and its B-17S, to leave Langley in early July 1941 and come to Washington DC to establish an Air War Plans Division (awpd). George agreed and notified Arnold that his division was open for business on 10 July—with a grand total of four people.61 The previous day, the president had sent a letter to the Secretaries of War and the Navy requesting their estimate of production requirements if the United States fought the Axis. To George, the president’s request was a godsend. He asked Arnold to obtain permission for the Air War Plans Division to draft the air portion of the plan.

Arnold agreed that the time was ripe to make a concerted bid for the independent application of air power. He convinced Brigadier General L. T. Gerow, chief of the Army War Plans Division, that George’s office was the best suited to determine Army Air Forces requirements. The significance of Arnold’s action was not lost on those around him. “We realized instinctively that a major milestone had been reached,” recalled then Major Haywood Hansell, who joined George’s group from the office of Strategic Air Intelligence. “Suddenly, without anywhere near the opposition we expected, we found ourselves able to plan our own future. How well we would plan and what success we would have in getting that plan past the Army General Staff remained a matter of uncertainty, but for the moment one of our fondest dreams had been realized.”62 On Monday, 4 August, Lieutenant Colonel George informed his officers that they would develop a plan for a prospective air war against Germany and Japan—and that they would complete the plan in nine days.

To guide the effort George assembled an extraordinary group of talented men. Lieutenant Colonels Orvil Anderson, Max F. Schneider, and Arthur W. Vanaman, and Majors Hoyt S. Vanden – berg and Samuel E. Anderson were among those who worked on developing the plan’s eighteen separate tabs.65 Yet the responsibility for the most important of those tabs, analyzing such topics as “Bombardment Operations against Germany” and “Bombardment Aviation Required for Hemispheric Defense,” went to George himself and the three men whom he handpicked to guide the plan’s development: Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth N. Walker, Major Haywood Hansell, and Major Laurence Kuter. George, Walker, Hansell, and Kuter knew each other well. All had taught at the Air Corps Tactical School, and all were stalwart disciples of the school’s strategic bombing theory. “We had one valuable asset going for us,” Hansell recalled. “We embraced a common concept of air warfare and we spoke a common language.”64

The red-haired Hansell, who bore the nickname “Possum” because of a scoop-shaped nose and a pointed chin, had already begun analyzing Germany’s industrial web. As an officer in Arnold’s Strategic Air Intelligence office since 1940, his job had been to gather information about the economic structure and air forces of Germany and Japan. After receiving minimal help—and even active resistance—from individuals in the War Department’s Intelligence office, he turned to specialists from the civilian community who had recently entered the military in the wake of Hitler’s aggression.65 Hansell relied on “the services of a PhD in industrial economics and an expert in oil” to pinpoint the vital links connecting the German war machine.66 He also benefited from the suggestion of Major Malcolm Moss, a former international businessman who knew that American banks had provided the Germans with most of the capital to construct their electric power system, and thought that those banks might possess drawings and specifications of the German facilities. The hunch proved correct, and also yielded diagrams of oil refineries. Using those materials, as well as information from scientific journals, the advice of his experts, and his own detailed knowledge of production requirements, Hansell prepared target folders for the German electric power and petroleum systems.

The “abc” discussions between British and American military staffs in early 1941 triggered a summer visit to Royal Air Force (raf) intelligence offices in Great Britain. While there, Hansell exchanged information on German targets. He found that his studies on oil and electric power were superior to the raf’s but that the British information on transportation, aircraft production, and Luftwaffe organization eclipsed his own findings. The British allowed him to take copies of their reports, and Hansell eagerly did so. He departed in mid-July with a collection of target folders weighing almost a ton, which he crammed into an American bomber. Upon returning to the United States, he joined George’s Air War Plans Division.

Ken Walker’s operational expertise, and Laurence Kuter’s staff work, complemented Hansell’s bent for technical data. A quicktempered chain smoker from Cerrillos, New Mexico, Walker barely missed combat in World War I, earning his wings nine days before the war ended. His work in developing formation tactics at Langley convinced him that defenses could not deter a well-orchestrated bomber attack, and he instilled this belief in his classes at Maxwell. After leaving the Tactical School faculty, he flew bombers in California and Hawaii. George considered him “one of the most brilliant and far-sighted officers in the United States Army.”67

The restrained Larry Kuter provided a stark contrast to Walker’s nervous intensity. Kuter also possessed considerable experience in bombers and had followed Walker as operations officer for Langley’s Second Bombardment Group. After his assignment to the General Staff in the summer of 1939—as the sole Air Corps officer in the Operations and Training section—he worked on tripling the size of the Air Corps into a 5,500-plane force adequate to defend the Western hemisphere. Walker deemed his expertise essential to designing a viable plan for a potential air war, and persuaded Spaatz—now Arnold’s chief of staff and a brigadier general—to obtain Kuter’s temporary relief from the General Staff.68 Kuter arrived for duty in the War Plans Division on 4 August—the date that George notified his staff of their nine-day deadline.

George’s group accomplished their marathon planning session in the recently constructed penthouse on top of the eighth wing of the old Munitions Building, located on Constitution Avenue between the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial. Hastily constructed during World War I as a temporary facility, the three – story, steel-and-concrete structure contained cramped offices separated by numerous partitions and concrete pillars. The daytime temperature in Washington DC that August hovered near ninety, and the penthouse absorbed the heat.69 Oscillating fans did little to relieve the oppressive conditions. Hansell later described the penthouse as “intolerably hot,” and recalled that “literally, when you put your hand down on your desk, your papers would stick to it.”70 Despite the heat, the short deadline kept George and his staff working in the penthouse until nearly midnight every night, and on two evenings they did not go home.71 The heat and the long hours frayed nerves and led to angry confrontations. On one occasion Walker railed at George that he could no longer work with Hansell, precipitating a similar outburst from Hansell/2 George smoothed the ruffled feathers, and throughout the nine-day ordeal he worked to promote harmony through a mixture of humor, aplomb, and dogged determination.

According to President Roosevelt’s directive, George and his staff were to determine Army Air Forces requirements that would guide American industry if war occurred between the United States and the Axis powers. The only restriction given George was that his proposal had to conform to rainbow 5, the overall war plan agreed to by the British and American staffs in May 1941. rainbow 5 designated Germany as the major Axis threat and stated that Anglo-American efforts would focus on defeating Germany first while maintaining a strategic defensive against Japan. Like Nap Gorrell in 1917, George realized that he could not estimate the number of aircraft needed without first determining bow air power would he used. In that regard, he faced a dilemma. Although he and his staff were convinced that strategic bombing could independently defeat Germany, they also had to submit a plan that was palatable to the Army hierarchy.

Just as Pershing had expressed concern over the airmen’s emphasis on independent air operations in World War I, Marshall, while favorably disposed toward strategic bombing, was likely to reject a plan making no reference to air support for the ground forces. The Chief of Staff had recently called for twelve groups of “Stuka-type” dive bombers in a proposed air expansion to eighty – four groups.73 Accordingly, George listed the American air mission as: “To wage a sustained air offensive against German military power, supplemented by air offensives against other regions under enemy control which contribute toward that power; to support a final offensive, if it becomes necessary to invade the continent; in addition, to conduct effective air operations in connection with Hemisphere Defense and a strategic defensive in the Far East.”74

By stating that an invasion of continental Europe might not be required, George acknowledged the planners’ faith that strategic bombing would eliminate the need for it. Yet George also acknowledged that air power would be available to guarantee an invasion’s success if the need arose. Six years earlier, as an Air Corps Tactical School instructor, he had asked his students whether air power could achieve a solo victory in war. He now aimed to construct an air campaign that answered that question with a resounding yes. The progressive notions of Tactical School theory formed the plan’s underpinnings; the challenge was to translate accepted beliefs, based on hypothetical applications against generic enemies, into a specific design against an enemy that was very real. Germany—a “modern” nation waging “modern” war—appeared to be an especially apt choice for testing Tactical School principles. If the test proved successful, the bomber offensive would yield victory—and serve as a vindication for air force autonomy.

Having determined that strategic bombing would be the essence of America’s air effort, George and his planners worked to identify those parts of Germany’s industrial web that contributed the most to Hitler’s war effort. Hansell’s studies while assigned to the Strategic Air Intelligence office were invaluable in this endeavor. Using them, planners concluded that the electric power, transportation, and oil production systems were the key components of the German economy. They decided that those systems could be wrecked by destroying 124 vital targets—fifty electric power plants, fifteen marshalling yards, fifteen bridges, seventeen inland waterway facilities, and twenty-seven petroleum and synthetic oil plants. This bombing would not only destroy German war-making capability, but also the “means of livelihood of the German people.” George’s group noted that civilians might also be attacked directly once their morale had weakened due to sustained suffering and a lack of faith in Germany’s ability to win the war. “However, if these conditions do not exist,” the planners cautioned, “then area bombing of cities may actually stiffen the resistance of the population, especially if the attacks are weak and sporadic.” If the industrial web theory was correct, German morale would crack without targeting residential districts.75

George and his planners realized that the destruction of Germany’s industrial apparatus would be no easy task. German air defenses—which now included radar—were formidable, causing the group to list “neutralization of the German Air Force” as an “intermediate objective, whose accomplishment may be essential to the accomplishment of the principal objectives.”76 Without achieving control of the air, the ability to wreck German warmaking capacity remained problematic; moreover, an invasion of France could not occur unless the Allies first obtained air superiority. George’s planners determined that air control through attrition was unlikely. Many industrial targets lay beyond the range of escort fighters, requiring bomber squadrons to rely on Walker’s formation tactics as they fought their way across Germany. “We knew that defensive firepower in the air would not suffice to defeat the Luftwaffe,” Hansell recalled/7 Neither would attacking German air bases, which were well dispersed and heavily defended. As a result, planners decided to attack the Luftwaffe before it left the assembly line. They designated eighteen aircraft factories, six aluminum plants, and six magnesium plants as essential to aircraft production, and added them to the list of vital centers earmarked for destruction.

Until negated, German air defenses would likely hamper bombing accuracy, and accurate bombing was essential to wreck Germany’s industrial web. Marginal weather also threatened to disrupt the precision bombing effort. Based on studies that Hansell obtained from the British, George’s group estimated that an average of only five days a month would be suitable for daylight operations over the Reich.78 The best weather occurred between

April and September. The prospect of stiff defenses and poor flying conditions, combined with George’s own experience from Aberdeen Proving Ground, caused planners to predict that raids on Germany would be 2.25 times more /«accurate than peacetime practice bombing.79 George demanded that bombers had to attack each target in sufficient force to achieve a 90 percent probability of destroying it—the same percentage deemed acceptable in similar problems at the Air Corps Tactical School.80 In addition—as Gorrell had pointed out in 1917—bombers would have to attack many targets more than once to prevent the Germans from repairing the damage. The planners anticipated that the Germans could repair most targets other than electric power facilities within two to four weeks; power plants would take longer to restore.81

George’s group next calculated the number of bombers required to guarantee a 90 percent level of destruction to the 154 key targets selected, given the expected accuracy and the need for repeated attacks. They determined that 1,100 bombers were necessary to ensure a 90 percent probability of destroying a single hundred-foot-by-hundred-foot target under combat conditions.82 A like number of aircraft would have to return to that target in two weeks to keep it out of action. Planners quickly realized that the aaf needed an enormous number of bombers to destroy the German war effort through constant pounding. George thought that dismantling German industry required at least six months of non-stop bombing, and planners anticipated an April-Septem – ber offensive to coincide with the most favorable flying weather. Given weather, maintenance, and crew rest limitations, they estimated that a bomb group containing seventy aircraft could send thirty-six of its bombers against Germany eight times a month.83 Thus, to wreck the 154 key targets in a six-month span would require ninety-eight bomb groups—or 6,860 bombers—at the start of the offensive.

Those bombers would consist of ten groups of B-25S and B-26S, twenty groups of B-17S and B-24S, twenty-four groups of B-29S, and forty-four groups of B-36S. Planners noted that the ideal type of bomber for the offensive was the в-29, a recently designed four-engine marvel; two-engine в-25 and в-26 “medium bombers” would suffice “only because they were available.”84 The vast numbers would swamp airfields in Great Britain, which would serve as home base for the B-17S, B-24S, B-25S, and B-26S. B-29S would operate against Germany from Northern Ireland and the Middle East. The в-36, a proposed behemoth with a four-thousand-mile range, could fly from Newfoundland, Greenland, Africa, India, or the northeastern United States. George’s staff anticipated that each group engaged in combat would lose 20 percent of its aircraft (and 15 percent of its flying personnel) per month, creating a requirement for an additional 1,272 bombers.8:1

Although the estimate of bombers needed to assault Germany dwarfed previous aircraft projections for the entire Army Air Forces,86 those bombers were by no means the only airplanes George and his planners envisioned. The massive air offensive against the Third Reich required fighters to defend air bases and support aircraft. Moreover, substantial numbers of fighters and bombers were needed to defend the Western Hemisphere, and the teeth of the strategic defensive in the Pacific would consist of B-29S and B-32S operating from bases in Alaska, Siberia, and the Philippines. All told, George’s group calculated that 239 groups and 108 observation squadrons were necessary to defeat the Axis—a grand total of 63,467 airplanes. If the United States began fighting, as anticipated, in the spring of 1942, planners thought that the nation would be hard pressed to produce such an armada before the end of 1943.87 Still, they believed that a land invasion of Germany in less than three years was unlikely, thus giving air power a chance to achieve an independent victory.88 A limited air offensive would start as soon as America entered the war, and the six month aerial pounding of the Reich would occur from April to September 1944. Charged with estimating manpower requirements, Kuter determined that by the start of the offensive the Army Air Forces would have expanded from its authorized limit of 152,000 men in August 1941 to 2,164,916, which was a half million more men than were in the entire Army at the end of 1941.89

On the afternoon of 12 August 1941, an exhausted Hal George delivered a copy of “awpd-i: Munitions Requirements of the Army Air Forces” to the Army War Plans office. The plan’s appearance reflected the rushed nature of the project. “It was not an impressive looking document,” Hansell remembered. “The pages were typed and mimeographed. Corrections were made in ink. The charts were black and white, hastily prepared and crudely pasted together.”90 Nevertheless, despite sweltering conditions and flaring tempers, George’s group completed their task on schedule.

Next came the job of persuading civilian and military leaders that the proposal was sound. George submitted the plan to the Army War Plans office without having it approved by Arnold, who was attending the Argentia Conference in Placentia Bay, but he knew that Arnold would have no qualms in endorsing it. Sterner challenges were on the horizon. In the following month, the planners briefed awpd-i to Robert Lovett (the new Assistant Secretary of War for Air), Army Chief of Staff Marshall, and Secretary of War Stimson. Lovett received the briefing on 13 August, accompanied by General Gerow from the Army War Plans Division and General Spaatz. A World War I Navy pilot and an outspoken air power advocate, Lovett avidly supported the proposal. Arnold heard the briefing with General Marshall on 30 August. The Army Chief of Staff said nothing until after the presentation was over and discussion had ceased. Then he commented that the plan had merit, and the next day scrawled “Okay, G. С. M.” on the cover of his copy.91 Andrews could claim a measure of credit for that signature. Like most Army generals, Marshall believed that air support for ground troops was essential, but Andrews had opened his eyes to the potential of independent air power. This impetus, coupled with Marshall’s practical nature, helped him endorse awpd-i. He realized that the invasion of Europe could not occur immediately if war came in early 1942, and Germany could not go unscathed during the buildup for the ground offensive. If strategic bombing could topple Hitler and eliminate the need for a risky amphibious assault, Marshall was willing to give it a try.

George’s staff culminated their “selling” of awpd-i on the afternoon of 11 September and the morning of the next day, when George, Walker, and Kuter briefed Secretary of War Stimson in his office in the Munitions Building. Stimson accepted the plan as “a matter-of-fact statement of the air forces required to defeat the Axis.” He cautioned, however, that the enormous number of men and planes necessary to implement the scheme “depended entirely upon the nation being in a war spirit or at war.”92

With the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December, America obtained the martial spirit that Stimson thought necessary to spur the large-scale production of combat aircraft. The turmoil created by Pearl Harbor canceled a scheduled briefing on awpd-i to the president, and Hansell later termed the lost opportunity “a cruel disappointment” because he believed that it prevented bombing advocate Roosevelt from fully understanding the value of a concentrated air offensive.92 Yet the seemingly inevitable march toward war in the late summer of 194г, with the Japanese defying Roosevelt’s oil embargo as they advanced across China, and the Germans threatening Atlantic sea lanes while they plowed toward Moscow, was likely a key reason that both Marshall and Stimson endorsed awpd-i without complaint. As historian Michael Sherry has observed, “Strategy, then, along with Roosevelt’s wishes about

how to fight the war, made the War Department amenable to a vision of air war that would have seemed repugnant and fanciful a few years earlier.”94

Although advocating strategic bombing, air planners understood that their proposal could not neglect the air needs of Army commanders, most of whom were skeptical of air power’s ability to achieve victory alone. Just as Gorrell had worked to convince Pershing that his plan for bombing Germany would not deny air support to ground forces, awpd-i specifically noted that air power would support an invasion of Europe if such an invasion proved necessary. Some airmen viewed the obligation to demonstrate that they would support their parent service as genuflection.95 Yet air planners could not ignore the concerns of the theater commander or Chief of Staff, who had to consider the possibility that independently applied air power might not prove decisive. That airmen received the green light to conduct strategic bombing was a tribute to the Andrews-inspired vision of George Marshall.

Marshall’s approval of awpd-г on the eve of Pearl Harbor guaranteed that the Army Air Forces would use it as a blueprint once war began, but the blueprint was not balanced. Air planners paid a great deal of attention to Germany—the designated primary enemy—and scant attention to Japan. In keeping with the tenor of the industrial web theory, they brushed aside such characteristics of the German state as its totalitarian government and Nazi ideology to focus almost exclusively on a mechanistic economic analysis. They also provided meager allowances for the unexpected— what Prussian military philosopher Carl von Clausewitz called “friction”—and the impact that such elements as chance, uncertainty, danger, and stress might have on an air offensive.96 The Germany that they depicted had mobilized completely, with its industry running at full bore in the wake of the assault on the Soviet Union. George and his group believed that the taut nature of the

TOO

German economy would increase its vulnerability to a precisely aimed air offensive, because no reserve capacity would be available to make up for the damage caused by bombing. The planners, especially Kuter, were painfully aware of America’s failure to flex its economic muscle in World War I. They believed that American industry would not allow them to wage total war for two years, and they knew that the Germans were already waging war on a global scale. The logical conclusion, it seemed, was that German factories must be producing at peak capacity.

Awpd-i’s analysis of Japan’s war machine paled in comparison to the mountain of data accumulated on German industry. “The allowances for defensive measures in the Far East were skimpy, to say the least,” Hansell later observed. “It was presumed that the U. S. Navy would be the primary agency for this requirement.”97 While working in the Strategic Air Intelligence section, Hansell had tried to identify Japanese vital centers, but the attempt proved fruitless. “The Japanese had established and maintained a curtain of secrecy that we found absolutely impenetrable. There were not even any recent maps available,” he recalled.98 The lack of information on Japanese production capabilities plagued air leaders throughout the war, and Hansell would learn that frustration firsthand as commander of XXI Bomber Command in late 1944.

Though far from perfect, awpd-i marked the culmination of American air power thought from Billy Mitchell through the Air Corps Tactical School. Much of the plan—like much of the Tactical School theory that spawned it—was based on faith. “Opportunities for reality testing were few”; most airmen dismissed the air power applied in Spain and China as too primitive,99 while the one concrete example of a modern air force attacking a modern nation—the Luftwaffe in the Battle of Britain—did not conform to American bomber technology, tactics, or strategy. Thus, the faith instilled by Mitchell, refined and dispensed by his Tactical School disciples, and blessed by air leaders sharing his vision provided the fundamental underpinning of American air power convictions.

Several articles of faith stood out above the others: the concept of a generic industrial web theory, with its presumed ties between a nation’s war-fighting capability and will to resist; the presumed vulnerability of those ties to bombing, and the presumption that severing them would result in surrender; the belief that a properly executed bomber offensive could not be stopped; and, finally, the progressive notion that a victory through air power would be quicker, and cheaper, than one gained through any other medium. At the same time, most airmen thought that an air power victory would vindicate an independent air force. The airmen subscribing to those beliefs were both sincere and pragmatic. They earnestly believed in air power’s ability to win a war single-handedly, and in its ability to do so efficiently, yet they realized that without proof for their claims they were unlikely to obtain an autonomous air force. Their faith in an independent air victory melded to their desire for an independent air service until the two became inseparable, as demonstrated by awpd-i.

In the end, individuals, as well as ideas, were the key elements producing a uniquely American bombing philosophy before Pearl Harbor. The distinctive backgrounds of Gorrell, Mitchell, George, Walker, Kuter, Hansell, Andrews, Spaatz, and Arnold—and countless others—contributed directly to an American approach to air war that manifested itself against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. Two years and eight days after the completion of awpd-i, the man who had found the Rex would lead more than one hundred B-17S in a dramatic raid against one of the major industrial targets of Hitler’s Third Reich. Curtis LeMay would play a key role in the effort to validate awpd-i’s progressive notions in both the European and Asian skies.

i. British Gen. Sir David Henderson pins the “Companion of the Distinguished Service Order” on twenty-eight-year-old Army Air Service Col. Edgar S. Correll in France,

April 1919. Relying extensively on British bombing proposals, Gorrell had authored America’s first plan for strategic bombing in 1917. (U. S. Air Force)

2. William “Billy” Mitchell spurred the development of progressive air power notions that guided a generation of American airmen. (U. S. Air Force)

3- Mitchell poses beside his command aircraft, the Osprey, a DeHavilland DH-4 from which he directed the bombing of the Qstfriesland in July 192.1. (U. S. Air Force)

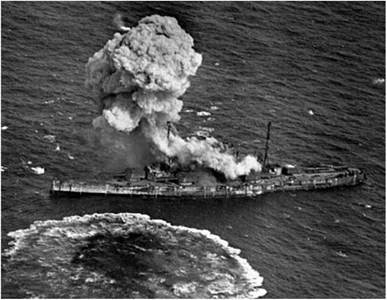

4- Billy Mitchell’s bombers attack the Ostfriesland off the Virginia Capes, 2i July 1921. (U. S. Air Force)

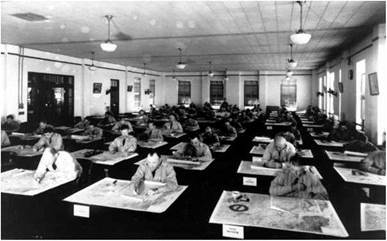

j. Air Corps Tactical School students tackle mapping exercises during the 1930s at Maxwell Field, Alabama. (U. S. Air Force)

6. Maj. Gen. Frank Andrews, commander of the ghq Air Force, sits in the cockpit of the first в-17 to arrive at Langley Field, Virginia, 1 March 1937. (U. S. Air Force)

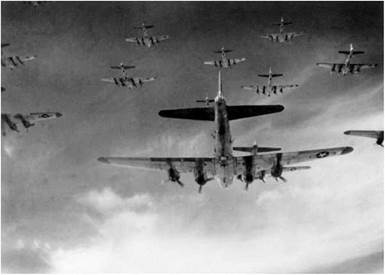

7. ghq Air Force B-17S intercept the Italian liner Rex seven hundred miles from New York City, 12 May 1938. (U. S. Air Force)

8.

Generals George Marshall, Frank Andrews, “Hap” Arnold, and Oliver Echols pose beside a glider at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, early in World War II. Marshall provided key support to Andrews and Arnold and their plans for a heavy bomber force. (U. S. Air Force)

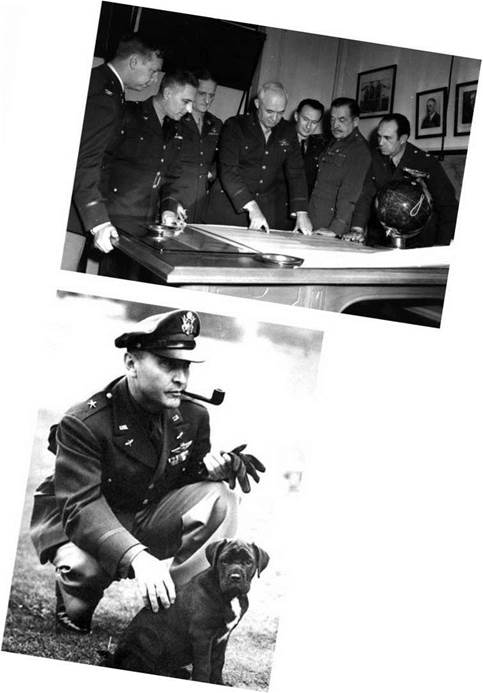

9. (Opposite top) Hap Arnold and members of his air staff in 1941. Left to right: Lt. Col. Edgar P. Sorenson, Lt. Col. Harold L. George, Brig. Gen. Carl Spaatz (chief of staff), Maj. Gen. Henry H. Arnold, Maj. Haywood S. Hansel! Jr., Brig. Gen. Martin F. Scanlon, and Lt. Col. Arthur W. Vanaman. George and Hansell played key roles in designing awpd-i, the Army Air Forces plan for bombing Germany, while Spaatz would attempt to bring that plan to fruition as Eighth Air Force commander in 1942 and the commander of U. S. Strategic Air Forces in 1944-45. (U. S. Air Force)

10. (Opposite bottom) Ira Eaker directed VIII Bomber Command in t942. During 1943, he led Eighth Air Force in the desperate battles for air superiority over Europe. (U. S. Air Force)

її. (Opposite top) Brig. Gen. “Possum” Hansell, First Wing commander, Eighth Air Force, and Col. Curtis LeMay, 305th Group commander, stand beside a B-17 at an airfield in Britain in spring 1943. Two years later LeMay, a major general, replaced Hansel! in the Pacific as the commander of XXI Bomber Command. (U. S. Air Force)

12. (Opposite bottom) The Boeing B-17 “Flying Fortress” was the workhorse of Eighth Air Force. This “G” model sported a chin turret to ward off frontal attacks from Luftwaffe fighters. (U. S. Air Force)

13. (Above) The Consolidated B-24 “Liberator” was one of the two main heavy bombers for the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces in Europe. It could carry a larger bomb load than its counterpart, the B-17. (U. S. Air Force)

14- The crew of the в-17 Memphis Belle at an air base in Britain on 7 June 1943 after completing twenty-five missions over enemy territory. For many bomber crews in 1943-44 the outcome was not as fortunate. (U. S. National Archives)

t5. (Opposite top) Luftwaffe defenses claim а В-Г7. The heavy bomber crews of Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces paid a steep price to win the daylight air superiority needed to launch the Normandy invasion. (U. S. Air Force)

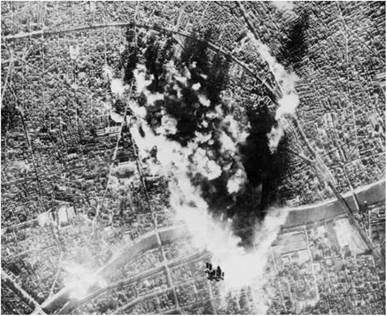

16. (Opposite bottom) Bomb release in an Eighth Air Force raid on a ball-bearing plant and an aircraft engine repair facility in Paris, 3 r December Г943. Following the costly raid against Schweinfurt on 14 October 1943, Eighth Air Force primarily attacked targets within range of escort fighters. Improvements in the P-47 “Thunderbolt” and P-51 “Mustang,” plus the addition of external fuel “drop tanks,” enabled bombers to have escort fighters to targets deep in Germany in early 1944. (U. S. National Archives)

17- A fighter pilot in World War I who shot down three German aircraft, “Tooey” Spaatz commanded Eighth Air Force in 1942 and then transferred to North Africa. He returned to Britain in 1944 as a lieutenant general and commander of the new U. S. Strategic Air Forces, with a mission to secure daylight air superiority over Europe to facilitate the Normandy invasion. (U. S. Air Force)

18. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Tooey Spaatz, and Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, the Ninth Air Force commander, at an airfield in Britain, May 1944. A month earlier Spaatz had turned over control of his heavy bombers to Eisenhower, and Eisenhower kept control of them until September to assure invasion support. (U. S. Air Force)

19- (Opposite top) Fifteenth Air Force B-24S pound Ploesti oil refineries in summer 1944. Despite the emphasis on supporting the Normandy invasion, Spaatz convinced Eisenhower to let him begin a concentrated attack on oil installations. (U. S. Air Force)

20. (Opposite bottom) The Messerschmitt factories at Regensburg, Germany, remained targets long after Curtis Lemay’s B-17S first attacked them on 17 August 1943. Flere, B-17S attack the complex on 18 December 1944. (U. S. Air Force)

21. (Above) Eighth Air Force B-17S unload incendiaries and high explosive bombs over Dresden on 14 February 1945 following a massive area attack by the RAF on the city the night before. Cloud cover obscured the American crews’ target, a rail junction near the city’s center, and most of their bombs fell on Dresden’s main residential district. (U. S. Air Force)

22.

B-17S from the 398th Bomb Group proceed to Neumunster, Germany, on 13 April 1945. By this point in the war the American portion of the Combined Bomber Offensive had devastated much of Germany’s industrial capacity and transportation network, but the cost

had been high for the attackers as well as the German populace. (U. S. National Archives)

23. (Opposite top) Frankfurt-am-Main in the aftermath of the Combined Bomber Offensive. Bombing wrecked most of Germany’s cities. (U. S. Air Force)

24. (Opposite bottom) Henry H. “Hap” Arnold became Commanding General of the Army Air Forces in June 1941 and soon led the mightiest air armada yet assembled. A driven, demanding leader, Arnold suffered four heart attacks during World War II. His first combat command came when he took charge of Twentieth Air Force in early 1944, and he directed the B-29 assault on Japan from his office in the Pentagon. (U. S. Air Force)

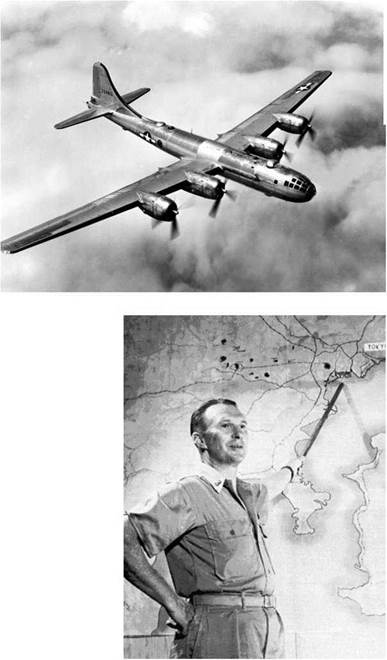

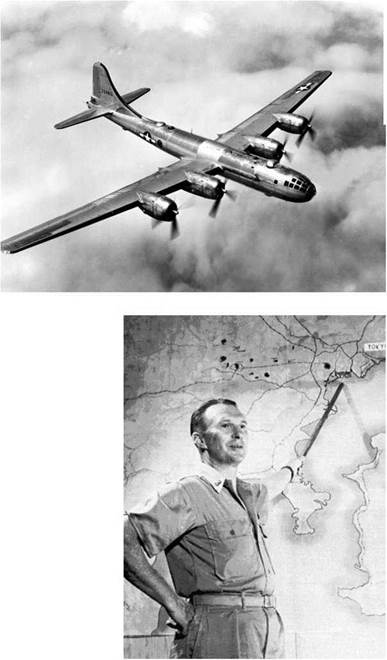

’ 5- (Opposite top) The Boeing в-2.9 “Superfortress” was the epitome in bomber technology, sporting pressurized crew compartments plus four gun turrets remotely controlled via General Electric analog computers. The aircraft was World War IBs most expensive weapon system, with a three-billion-dollar price tag. (U. S. Air Force)

z6. (Opposite bottom) Brig. Gen. Haywood S. “Possum” Hansell, XXI Bomber Command commander, briefs B-29 air crews before a mission to Tokyo in late 1944. His steadfast commitment to prewar progressive notions about bombing contributed to Arnold’s decision to replace him with LeMay. (U. S. Air Force)

27. (Above) Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, far left, replaced Brig. Gen. Possum Hansell, center, as XXI Bomber Command commander in January 1945. LeMay, who had previously commanded XX Bomber Command in China, was replaced in that job by Brig. Gen. Roger M. Ramey, far right. (U. S. Air Force)

28.

Brig. Gen. Lauris “Larry” Norstad, who served on Hap Arnold’s advisory council as a colonel in 1943 before becoming a staff officer in North Africa and Italy, replaced Possum Hansell as Twentieth Air Force Chief of Staff in summer 1944. Norstad wielded considerable power in that position, especially after Arnold suffered his fourth heart attack of the war in January 1945. (U. S. Air Force)

29. The Etiola Gay dropped the atomic bomb “Little Boy” on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945. (U. S. Air Force)

30. By June 1945 most of Kobe, one of prewar Japan’s four most populous cities, was in ruins. (U. S. Air Force)

31.

(Opposite top) Twentieth Air Force devastated Tokyo. (U. S. Air Force)

32. (Opposite bottom) Coi. Paul Tibbets’s Enola Gay is prepared to upload the atomic bomb for Fliroshima. (U. S. Air Force)

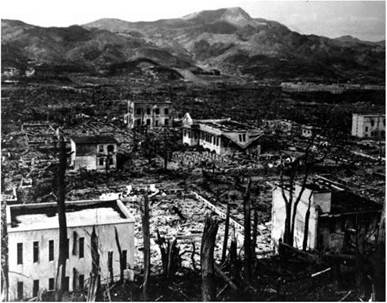

33. (Above) Nagasaki following the atomic strike on 9 August 1945.

(U. S. Air Force)

34- In the post-Vietnam era Col. John A. Warden III emerged as heir to the progressive notions that had sparked Billy Mitchell and Air Corps Tactical School instructors. Many of Warden’s ideas underpin current Air Force bombing doctrine. (U. S. Air Force)