Vickers Viscount

Whenever a new technology is introduced, there is always the inevitable first and best model, or brand, or demonstrator. In the new postwar world of turbine- propeller aviation, the Vickers Viscount was that leader, and the one to beat.

In answer to the Brabazon Committee’s 2B outline request for a commercial transport capable of carrying 24 passengers at 280 mph over a distance of 700 miles, Vickers responded with a proposal called the VC-2 Viceroy. This design used four of the new Rolls-Royce Dart engines, and after BEA took a strong interest in the concept, the capacity was increased to 32 passengers. The prototype airplane was known as the 630, and its first flight took place in July 1948.

The prototype was seen absolutely everywhere, at first showing off at the Farnborough displays, commonly flying with three of four engines shut down,

then after its type certificate was granted in 1950, official sales tours and proving flights were initiated.

As the capabilities of the Dart engine grew, so did the Viscount. (The name Viscount was exchanged for Viceroy after the independence of India from the British Empire.) Employing the new Dart RDa3 Mark 504 powerplant in the 700-series airplane, the 50-percent increase in power allowed the fuselage to be lengthened by 6 feet 8 inches, and the wingspan to increase by nearly 5 feet. First flight took place on August 28, 1950. The range of this larger aircraft was now nearly 1,000 miles. The passenger load increased once again, this time to somewhere between 40 and 53 seats, and this ultimately refined design was now the production standard with which to begin the Viscount assembly line.

Airline passenger service first began with BEA and a 701-series Viscount on April 18, 1953, on a flight from London Heathrow to Rome, Athens, and Nicosia. Because the last leg was under contract to Cyprus Airways, that line holds the distinction of being second in the world to carry passengers on a Viscount. Even as this new groundbreaking service was starting, just a few days prior BEA had signed a contract for the new, larger Viscount 802, capable of carrying 70 passengers at 325 mph.

Considerable interest for or about the Viscount was also stirring in North American airline boardrooms, and to satisfy the regulatory bodies of Canada and America, Vickers drew up the 724-series airplane. Capital Airlines immediately ordered 60 airplanes, an absolutely gigantic number in 1954! This then became the production standard airframe and was known in

general as the 700D. The D model had Dart 510 engines. Capital introduced the Viscount to passengers in the United States in July 1955. Trans-Canada Air Lines, which operated 34 of the new turboprops, holds the honor of making the first Viscount flights in North America by virtue of beginning service on April 1,1955.

By 1956, more than 200 Viscounts had been ordered. The British finally had a world-beater airliner design, which was selling beyond wildest expectations. Passenger acceptance was off the charts as well, what with the fast, smooth, and fairly quiet behavior of this airplane. The large vertical oval windows were part of the joy of flying in a Viscount, as one could see everything!

In short, the Viscount was indeed a truly stunning development within the airline world. Capitalizing on that success, Vickers made the seemingly inevitable decision to stretch the airframe. As mentioned above, BEA was the instigator for a higher-capacity airplane, and initially liked the 801 series, which was a whopping 13 feet longer than the 700 and could carry up to 86 fares. Sober consideration prevailed, and the 802 was born to take the place of the 801, with a mere 46-inch extension of the fuselage. Moving the fore and aft bulkheads allowed for the large increase of cabin space, in spite of the small external stretch, and 68 of these airplanes wound up being delivered to six carriers.

Although the 802 was a simple stretch of the 700, which meant more passengers over a shorter or same distance, the final Viscount type, the 810, really was the penultimate development of the design. The same size as the other 800 airplanes, the 810 was matched up with the new Dart 525 engines, which allowed for an

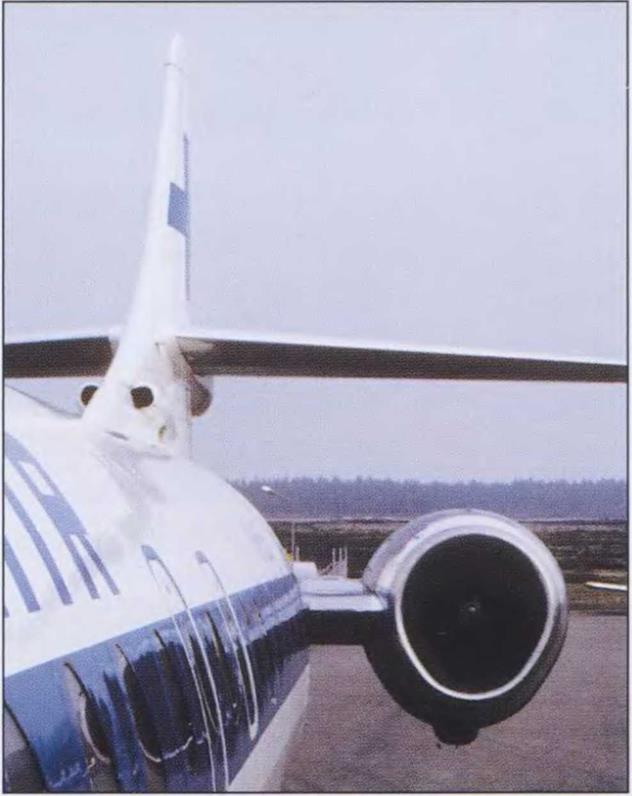

As Great Britain was the first with a turbojet-powered transport, so it was again with the world’s first production turboprop transport—the inimitable Vickers Viscount Although smaller than the Lockheed Electra that would come later, the Viscount entered service with BEA in 1953 and brought the advantages of faster and smoother turbine power to the world’s airlines well before the big jets later in that decade. (Vickers/Mike Machat Collection)

Capital Airlines became the first Viscount operator in the United States, flying more than 60 of the type from 1955 until its merger with United Air Lines six years later. The forty-second airplane was delivered from Vickers’ Weybridge, England, factory in September 1956. The new turboprop was a solid hit with passengers when it first entered service, despite the shrill note of its Rolls-Royce Dart engines. (Jon Proctor Collection)

impressive 17-percent increase in maximum gross takeoff weight. This then translated into nearly doubling the aircrafts range —and now the Viscount really had something to it.

In the United States, the premier operator of the final version was Continental Airlines. It started commercial operations in May 1958, and owned 15 Viscounts. Overseas, it was Lufthansa and Austrian flying the 810, among several other airlines worldwide. When all was said and done, with the last delivery of a Viscount to China’s CAAC in 1964, the airplane carried the distinction of being Britain’s most successful airliner in terms of number built and sold. Final score: 60 operators in 40 different countries, and more than 150 second-hand operators as well.

Bristol Britannia

The Bristol Britannia was one of the great shortfall stories of British commercial aviation. It was an airplane with so much promise, but a case of bad breaks and ultimately poor timing nipped this beautiful airliner in the bud.

Beginning life as the chosen design to satisfy the Brabazon Committee’s Type 3 airline transport, the original series 100 Britannia was far different than the production machine. The initial design only needed to meet the requirement for 1,500-miles range and around 32 passengers. As with everything in the postwar period the airframe grew until the type was redesigned for

BOAC to “175 standard,” which translated to carrying 90 passengers over 2,740 mile.

Another crucial and fateful design change was made prior to the first metal being cut: replacing the Centaurus piston engines with Bristol’s Proteus turboprop powerplants. Herein lay the diminution of the Britannia as the years passed.

First flight of the aircraft took place in August 1952 with a 101-series airplane. One other prototype flew in December 1953, and the first airline service began on February 1, 1957. (We mention the beginning and ending numbers to highlight the enormous lag time until service entry.) The flight-test program was dogged by a few problems, but most notably, the Proteus engines were completely unreliable and prone to an unusual icing condition, which would, in eventual progression, “suffocate” the engines and lead to inflight shutdowns. The problem was eventually diagnosed and a suitable fix was designed, but much valuable time had been lost in the interim.

Originally anticipating a large swell of orders from the world’s major airlines, Bristol contracted with Short Brothers in Belfast, Northern Ireland, to utilize their production facilities as a second assembly line. As the engine problems dragged on this became less a necessity, but the 250 series was built on that line with a forward cargo door and a standard load of passengers aft.

The late-development series of the airplane was the 300. Sporting a longer fuselage with greater range, the

|

|

|

The Canadian-built CL-44 served with Flying Tiger Line, as evidenced by N229SW, which was acquired in a merger with Seaboard & Western. A novel feature of this Britannia variant was the swing tail that opened 90 degrees for rear fuselage cargo loading and unloading, (via Paul Nowaske)

“Big Britannia” could now carry 114 passengers over a huge 4,100-mile range. BOAC flew the 312 on routes that included London Heathrow to New York, but the airline eventually encircled the globe with its fleet of Britannias. Canadian Pacific and El A1 also utilized the 310 Britannia with its long intercontinental legs.

Perhaps two of the most fascinating Britannia airline orders that never materialized were from Capital and Northeast. Both were avid Viscount operators that needed additional passenger carriage and nonstop range for their premier routes and, therefore, looked to the British and their lead in turbine-propeller development for the answer. The Britannia fit the bill perfectly: long range and high capacity in the 300, and a luxurious ride

to boot! Bristol produced the first aircraft for both carriers, even painting the airliners in each company’s respective colors, with the Northeast airplane looking especially stunning in its midnight-blue-and-white livery. But for reasons of financial health and the cold reality of the Britannia simply being the wrong aircraft for those airlines at that particular time, the orders were canceled and the airplanes were placed with other carriers.

The Bristol Britannia was known as “The Whispering Giant,” and the name was quite apt. This elegant and efficient airplane might have reached a great pinnacle in airline history, but alas, fate was just not kind to the big, graceful airplane from Filton. Only a mere 85 Britannias were built.