Perhaps the greatest impediment to the widespread acceptance of air travel as the key mode of transportation in this country, and around the world for that matter, was the ever-present perception of the danger of flying. During the 1920s and 1930s, survival in air transportation was almost akin to living in the Wild West of the nineteenth century, comparable to traversing the country in covered wagons through Indian territory. Airliner crashes became constant newsreel fodder, and mothers begged their sons to take the train and not fly. The Fokker Trimotor or Curtiss Condor seemed like lumbering box kites just waiting to be swatted out of the sky by a fierce storm.

However, each successive decade following World War I did indeed manage to see incremental and then quantum advances in aircraft design, and as a consequence, airframe and systems reliability marched steadily forward. Compare the change from the wooden Fokker X to the all-metal Ford Trimotor. It was a wooden-wing spar in a Fokker that broke apart in a thunderstorm killing famed Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne and galvanizing public sentiment against air travel. It was nothing less than a tectonic shift from the corrugated Ford to the sleek monocoque Boeing 247, and then the grand DC-3 in 1936.

These aircraft brought new standards of flying safety and reliability, but all things remained relative, and airplanes still had a nasty tendency to crash. As discussed later, the airlines of the 1930s were obsessed with advertising campaigns aimed at bolstering the safety of flight and the quality of their product. American Airlines even went so far as to broach the subject of safety in their ads. That frankness seemed to have a positive effect overall, but flying was still not like taking the old, dependable train.

Following World War II, four-engine transports like the Lockheed Constellation and Douglas DC-6, along with the new twins from Convair and Martin, launched the next refinement of the technological base featuring pressurized passenger cabins and strong all – metal construction utilizing new advanced aluminum materials. Augmenting this were radio navigation aids, a flight engineer to handle the new complex technologies, weather mitigating devices such as heated wing and tail leading edges and propeller deicing systems, and of course, the obvious redundancy of two more engines on the larger transports.

And yet, airliners kept running afoul of consistent safety records. Airplanes still crashed often enough to give many folks a fleeting second thought before boarding a “giant silver bird” or “queen of the sky” bound for points near and far. Train service continued to maintain its passenger appeal even throughout the 1950s. So what was causing that persistent, albeit lowered, sense of worry when it came to flying commercially?

The Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) mandated that all Low – and Medium-Frequency (LMF) radio ranges be decommissioned in favor of new the technology, Visual Omni Range (VOR). Lighted airways were nearly a relic of the past, leftovers of the airmail open cockpit days. Most major airports were now equipped with Instrument Landing System (ILS) precision approach aids, and en route traffic radar centers popped up across the nation to separate airplanes from one another along the airways. Aircraft were flying higher and avoiding more weather, flying faster to stay ahead of that weather, and flying with greater fuel range

|

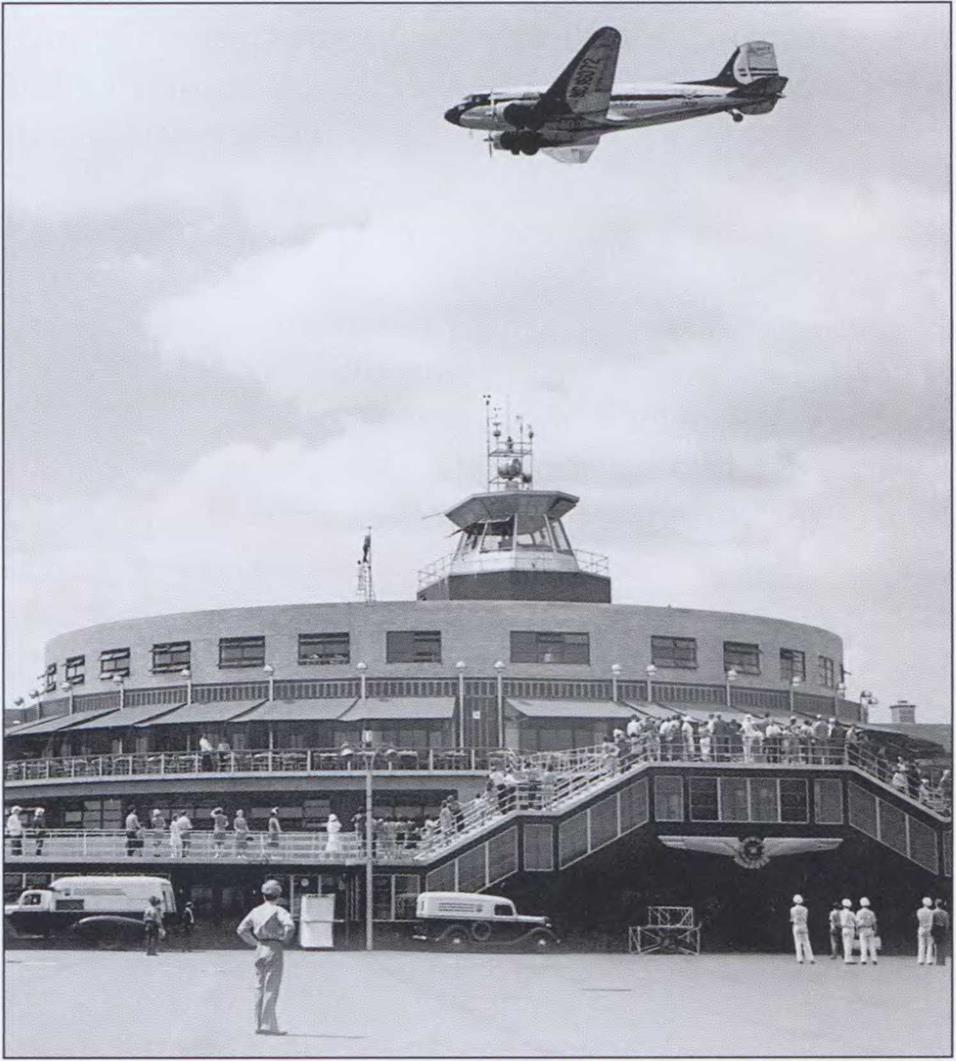

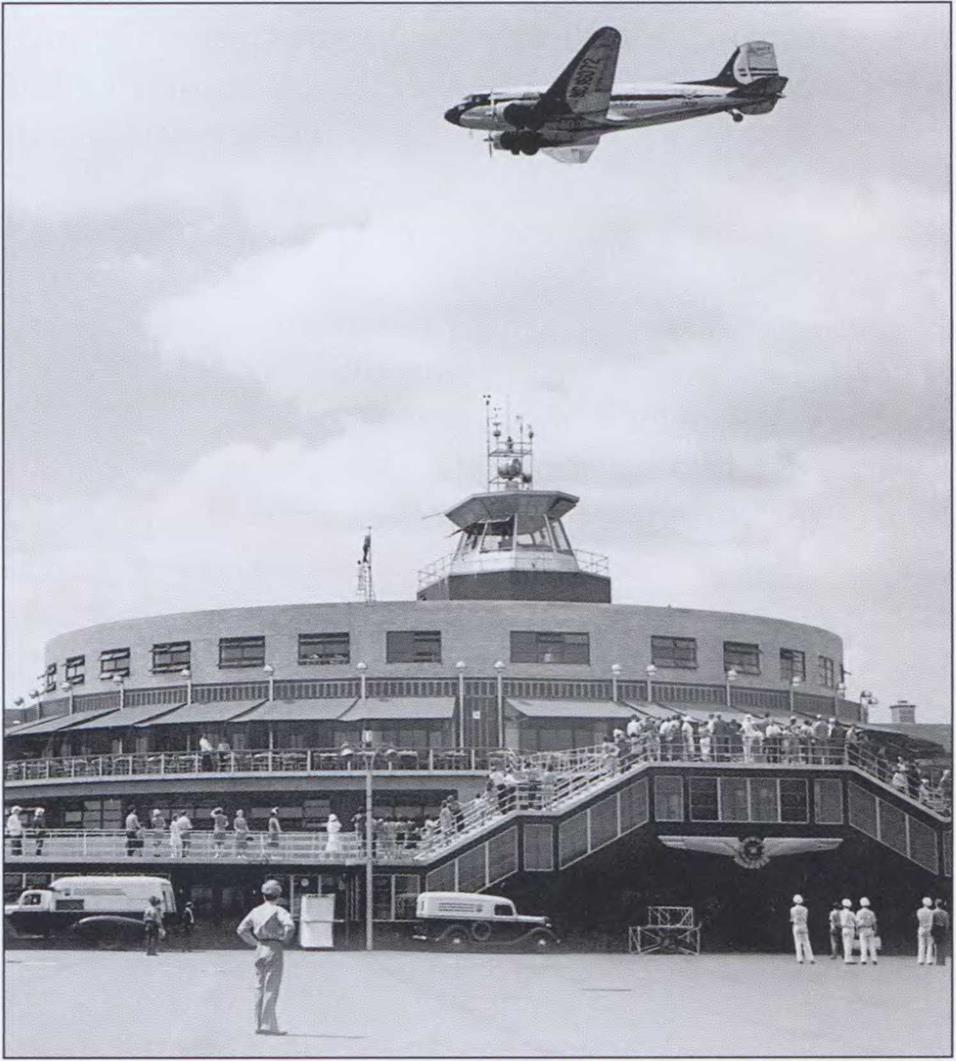

As the airline industry matured and grew, new modern "super airports" came into existence to serve the equally new and modern airliners carrying more and more passengers every year. Here we see a gleaming new LaGuardia Airport terminal and tower with a United DC-3 flying overhead in 1939. The terminal building contained a glamorous restaurant and sweeping observation deck back in the day when a trip to the airport was considered an exciting excursion for the entire family. (Mike Machat Collection)

|

so as to be able to go around that weather. Advanced weather radar onboard the DC-6B, DC-7 series, and 1049/1649 Constellation series (covered in Chapters 3, 4, and 5, respectively) all added more margins of dependability to daily airline operations. So why were airliners continuing to fall out of the sky?

For all the technology invented to improve piston – powered airplanes, and as the working and regulatory environment for fast aircraft continued to grow (although always seemingly behind the latest speed and efficiency of the airplanes it served), it appeared that two chronic problems kept hampering a better safety record for airliners in the late 1940s and the 1950s: unreliable technology and weather.

Piston engines such as the Wright R-3350 Turbo Compound or Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Double Wasp certainly marked the pinnacle of reciprocating power – plant technology and made possible the advancements noted above, but the very complexity of these engines was also their Achilles heel. More complex than a Swiss watch, these engines required as much maintenance per – flight-hour as several fleets of DC-3s combined! They certainly were not reliable. How many DC-7s landed at their destinations with one engine shut down, its propeller feathered? How often did contemporary films characterize airliner engines as being temperamental and cantankerous devices that came apart in flight, threw propellers, and then burned up, terrorizing all passengers onboard?

When one examines hull loss statistics in the United States from 1946 to the present, the overall number of accidents still falls within a pretty narrow range. The negative trend, however, existed in the types of hulls destroyed. A striking reality found in the probable cause of each accident in the prop era identifies the aircraft more often than not as a commercial transport. As years pass with the world’s airlines fully transitioning to all-jet fleets, the same number of accidents then begins shifting more to general aviation or small regional aircraft. Today, air safety for commercial transports around the world, and especially here in the United States, is enviably exemplary, with more people flying per-airplane, per-day, and on more airlines and airplanes than ever imaginable in the early 1950s.

Although technology has truly made a life-sustaining difference to air travelers today, aviation still suffers the occasional grandiose air accident with its attendant headlines, especially those involving large jetliners with hundreds of passengers aboard. What is the explanation? Many times we still see weather as a culprit, for we just cannot surmount every single type of atmospheric disturbance Mother Nature sends our way. Mighty jet airliners have been ripped apart by thunderstorms, and ice is still the largest operational problem faced by the air transport industry. Let’s flash back to earlier times and imagine flying in a Constellation somewhere over the East Coast in February.

The airplane is flying in ice more than in the clear; and because the Connie uses rubber deicer boots on its leading edges, you can actually see the wings icing up, then the boots expanding to break sheets of it loose. It even shears off the prop blades and slams against the fuselage. The weather is abysmal all the way down to a near zero-zero landing and you’re landing at a field without an ITS, so the Captain is conducting a VOR, or in really tough situations, an ADF (Automatic Direction Finder) approach.

Landing minimums are higher for these non-precision approaches, which means you may or may not see the ground from those slightly higher altitudes. Hopefully the wind isn yt so strong that you are blown completely off course, placing you farther away from your missed approach point, where you either see the runway or have to execute a go-around and try again, or even divert to your landing alternate.

Our pilot has flown into this airport “a million times" and he’s sure he knows where he is by looking straight down at the ground. If only he can get a few feet lower and sneak into the clear to be able to see the runway straight ahead. As he gingerly continues to feel for clear air; the copilot suddenly screams, “Pull Up!”

But with engines snarling with increased power to escape impending disaster, the ground rushes up to meet the aircraft, the left wingtip contacts the earth, and the rest of our story becomes tragic front-page news the next morning.

More the exception than the rule, the above scenario focuses again on an inherent complexity, and how this aspect of postwar propliner operational capability affected air safety. Flying a large, piston-engine airliner, already an extremely complex system, within another incredibly complex system (radio navigational aids) while at the mercy of a precocious and unpredictable weather phenomena is just begging for the ominous chain of events found in all air accidents to be forged, several links at a time.

It is, therefore, a vast tribute to the men we called aviators in those days that many a safe trip was concluded at their hands despite all the challenges. By the late 1950s, these incredibly talented and wise individuals began to experience first-hand the almost unbelievable improvement in safety standards, and the simplicity of flight operations made available to the airlines when the world finally transitioned from props to jets.

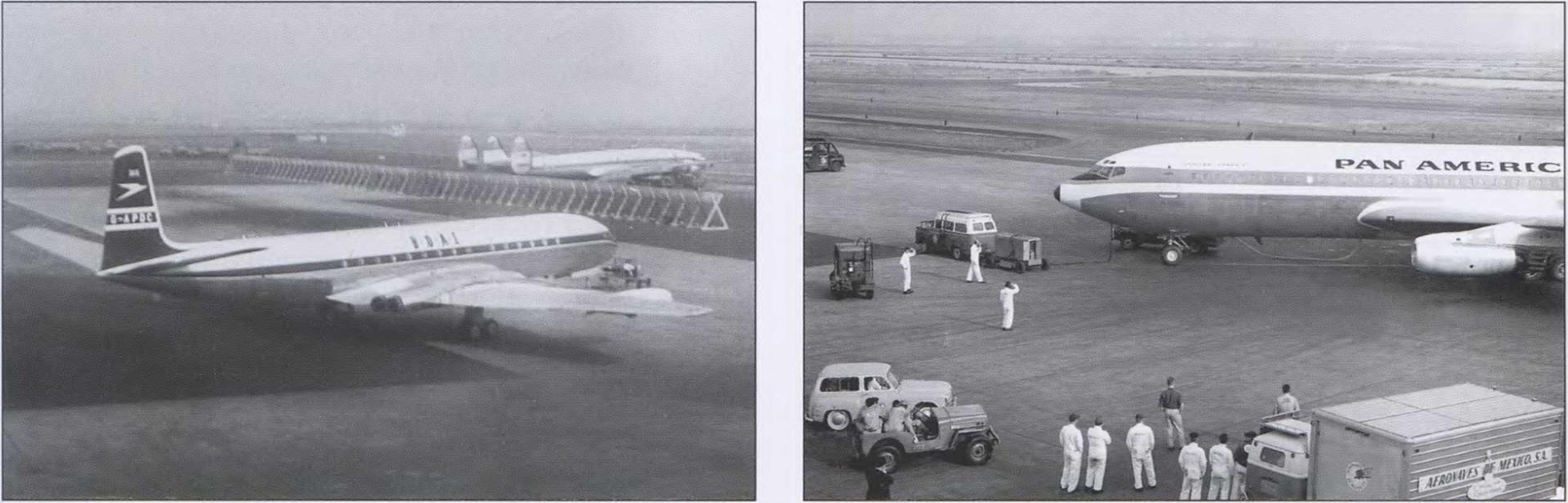

Complete with all the associated pomp and circumstance, Pan American’s first Boeing 707 service from New York to Paris prepares to receive its passengers at Idlewild on a rainy autumn night, October 26, 1958. Although a BOAC Comet 4 snuck under the wire two weeks earlier to beat the 707 to the punch inaugurating the world’s first transatlantic jet service, Pan Am

Complete with all the associated pomp and circumstance, Pan American’s first Boeing 707 service from New York to Paris prepares to receive its passengers at Idlewild on a rainy autumn night, October 26, 1958. Although a BOAC Comet 4 snuck under the wire two weeks earlier to beat the 707 to the punch inaugurating the world’s first transatlantic jet service, Pan Am